Exploration

For Whom The Shipwreck Bell Tolls

Many wreck divers consider a ship’s bell to be the quintessential artifact to find and recover. Here prolific shipwreck explorer, historian, and author Gary Gentile recounts his and colleagues’ adventures recovering bells from numerous well-known shipwrecks including the Andrea Doria. He regards these efforts as rescuing our cultural heritage from the ravages of the sea.

Text and images by Gary Gentile

🎶🎶 Predive Clicklist: Hell’s Bells by AC/DC

The best way to start an article about ships’ bells is to quote the entry in my book, The Nautical Cyclopedia (1995):

“A bell has many purposes: It can call the crew to dinner, sound an alarm in the fog, signal distress and emergencies such as fire or imminent collision, and announce the time of the watch. A bell is struck when coded signals are used, such as to denote the hour and half hour, and rung rapidly when making a tocsin call.

A ship’s bell’ is generally cast from brass with a small quantity of silver added to the alloy in order to give the ring a more penetrating pitch. The clapper is generally made of iron because iron striking against brass gives a better tonal quality than brass striking against brass. The ship’s bell traditionally has the name of the vessel engraved upon it, and sometimes the date of manufacture. A bell may weigh as little as 14 kg/30 lb, or it may weigh over 450 kg/1,000 lb. A vessel may have more than one bell, which may be mounted on a davit near the bow, such as on the forecastle; on the foremast above and within reach of the crow’s-nest; on the forward bulkhead of the wheelhouse; on a davit in the stern; or some other convenient place.”

Wreck divers consider a ship’s bell to be the quintessential artifact to find and recover because the bell symbolizes both the heart and the soul of a ship and therefore of a shipwreck. Better yet, the bell of an unidentified shipwreck may establish the wreck’s identity.

The photos that follow comprise a recitation of shipwreck bells with which I have been fortunate enough to be involved.

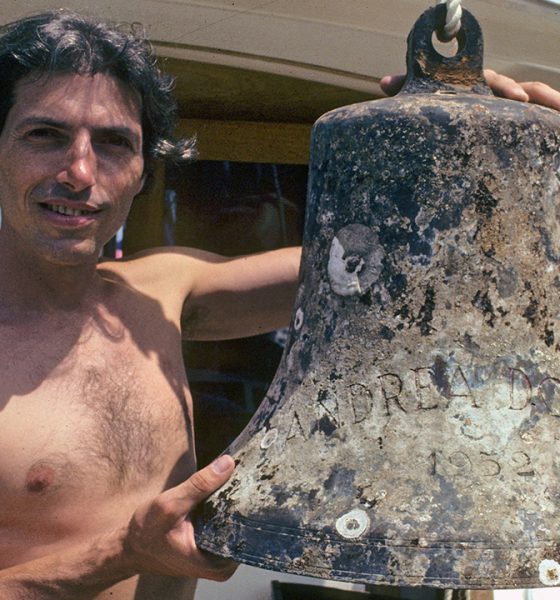

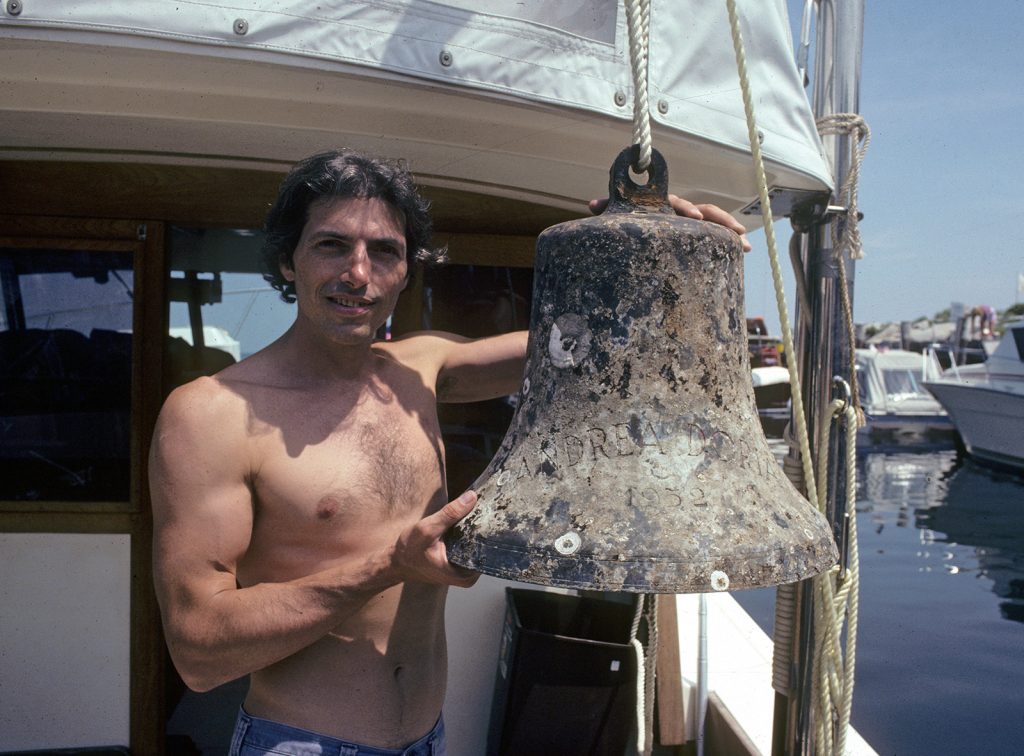

Andrea Doria

In 1985, Bill Nagle organized a five-day expedition to recover the bell from the bow of the iconic Italian liner, the Grand Dame of the Sea, which lay at a depth of 74 m/240 ft. Volunteer helpers included Mike Boring, Kenny Gascon, Artie Kirshner, John Moyer, Tom Packer, and me. After three days of searching, we were unable to locate the bell, either on the wreck or in the sand below the davit where the bell should have been hung. So, we each went our separate ways to explore the wreck.

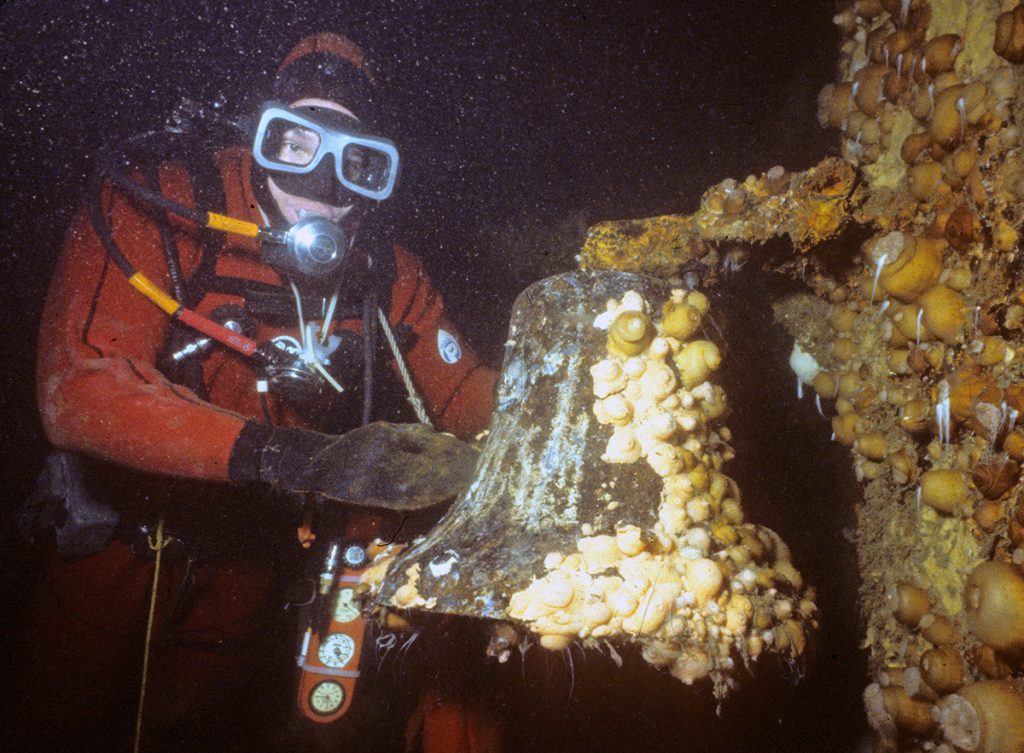

I had been on several cruise ships that boasted bells in the stern, so my dive buddy Tom Packer and I swam 53 m/175 ft along the upper hull to the aft steerage area. Above the emergency steering helm, we spotted an object that was so covered with sea anemones that they deformed and disguised the object’s true curved contours. I used my knife to scrape off enough anemones to read the name and date on the barnacled brass surface: “Andrea Doria,” and beneath it, “1952.”

It took the team two more days to free the bell from the steel rod that held it in place.

Sitting left to right are Bill Nagle and John Moyer.

Manuela

In 1987, I was diving on the wreck of the freighter Malchace with an express purpose in mind: to explore the forecastle in search of the ship’s bell. I describe this quest in my book, Wreck Diving Adventures (1994):

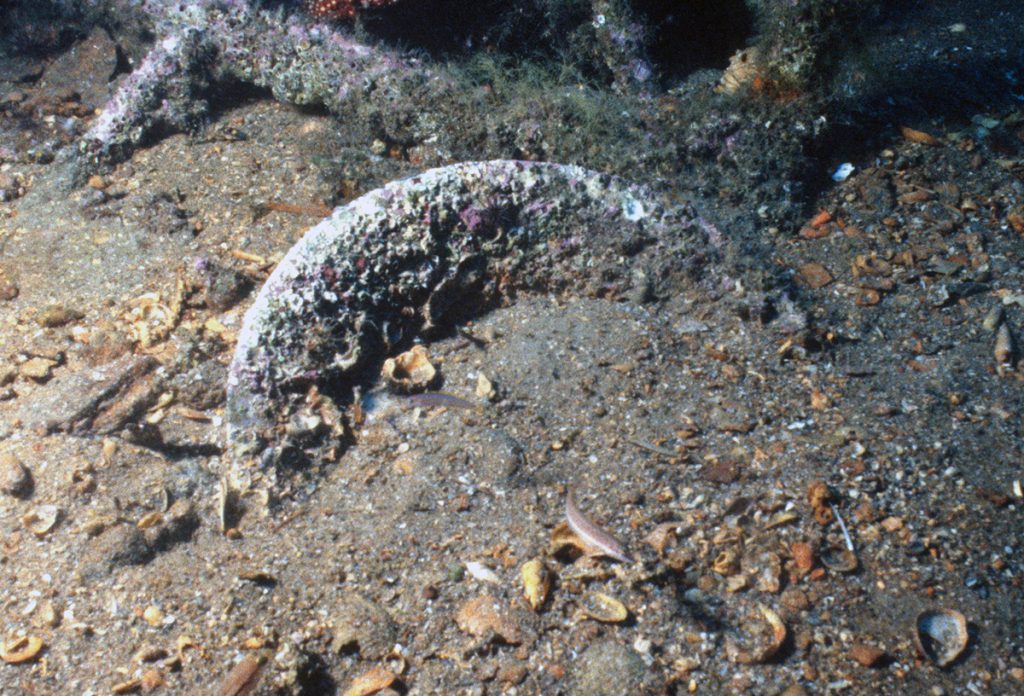

“The bow of the Malchace is separated from the main hull and lies perfectly on its starboard side, with the main winch and deck machinery still precariously in place. I approached this large intact portion with my shutter snapping, when my eye caught the glint of something protruding out of the sand. I dropped down to inspect it: A curved piece of metal perhaps 2.5 cm/1 in high and 20 cm/8 in long presented an arc which could have been the flared end of a flange.

“A quick scrape with my knife revealed a smooth brass surface under the thin layer of encrustation. I fanned the sand to reveal more of the object, then dug in earnest. Within moments, I uncovered a circular rim that grew in thickness from the top, and that narrowed its diameter under the sand. I backed away and shot a picture.

“With both hands I scooped out sand from the middle. Not until I exposed the clangor was I absolutely sure it was the ship’s bell.”

Finding and recovering are two different processes. I was unable to pull the bell out of the sand. It was too deeply embedded, and I speculated that it might still be secured to its davit. Recovering the bell was going to be a monumental task that needed the help of every diver on the boat: Jim Anderson, Dave Antolic, Jim DiPreta, Paul Gacek, Scott Jenkins, Artie Kirchner, Joe Pavia, Mel Rich, and Richard Smith.

That night I purchased three 4-inch C-clamps from a hardware store in Ocracoke, North Carolina. The next day we returned to the wreck site. I descended first, set the hook, swam to the bell, and sent up a lift bag which I tied to a nearby beam. Next in the water were Jenkins and Smith, who took down a heavy nylon line which they secured with a choker knot around the bell’s flared bottom. They also attached the C-clamps to the bell and secured a 227 kg/500 lb lift bag by weaving its lifting strap through the middle of the clamps.

Three teams of divers then dug out the bell, tightened the clamps, and partially inflated the lift bag. Finally, Kirchner chiseled apart some steel beams that the diggers had uncovered and completely filled the lift bag. We slipped free of the anchor line, pulled in the slack to the nylon line, lashed the line around the starboard bitt, reversed the engine to put tension on the nylon line, and increased RPMs until the bell was lifted out of the sand. The lift bag burst to the surface with the bell suspended below it.

The well-orchestrated plan confirmed the efficacy of teamwork.

After the brass came the irony. When I cleaned off the bell, the name that was etched in brass was not Malchace, but Manuela: a freighter that reportedly sank a mile away. After both vessels had been torpedoed by German U-boats during World War Two, the wrecks had been charted incorrectly. There was no doubt that the inshore wreck in 47 m/155 ft of water was the Manuela. I later confirmed that the offshore wreck, which lay at a depth of 63 m/205 ft, was the Malchace.

Nova Scotia

Two months after the recovery of the Manuela bell, I dived off Canso with Lynn Del Corio and Myles Wagner. We were searching for shipwrecks but not finding any when we arrived at a ledge where the depth dropped from 15 m/50 ft to 25 m/80 ft. Lying on the deeper sand was what appeared to be a naval contact mine from World War Two, complete with detonation horns.

Lynn charged downward while Myles and I descended at a more leisurely pace. The “mine” turned out to be a sunken bell buoy. The detonation horns were stubs of steel beams from the cage that protected the bell. We did not have lift bags, so I secured a sisal decompression line to the bell’s top hanger and swam it to the boat.

I then grabbed a 227 kg/500 lb lift bag and followed my deco line down to the bell. Because I was using the same set of tanks, I did not have enough air to do more than inflate the bag enough to float it upright. I returned to the boat where I rigged a regulator to a spare single tank. I convinced a deckhand (whose name I did not record) to use the tank to fully inflate the lift bag. Within a few minutes, the lift bag bobbed to the surface. I pulled it to the stern of the boat where the real work began.

Fortunately, our chartered boat was a workboat complete with a hoisting boom. It took all of us to lift the bell out of the water and swing it onto the transom. After I took some photos, we swung the bell down to the deck.

The bell buoy had drifted a long way from home. Etched above the rim were the letters USLHS—United States Light House Service. We later learned that the bell weighed more than 136 kg/300 lb.

Sebastian

In 1994, John Chatterton organized an overnight trip to investigate a pair of hang numbers that we hoped would be the sites of the tanker Pan-Pennsylvania and the U-boat that sank her: the U-550. The wrecks lay offshore of the Andrea Doria. On the way to the first site, we stopped over another set of hang numbers. The depthfinder revealed a huge object that stood 15 m/50 ft high in 77 m/250 ft of water.

We continued throughout the night to the next set of numbers. This was indeed the Pan-Pennsylvania. The wreck lay upside down at a depth of 77 m/250 ft but had a relief of only 6 m/20 ft: a real disappointment, because we saw nothing but the bottom of the hull. There was no wreck at the third hang spot. Everyone voted to return to the first target.

Chatterton wanted to be first to dive on the site. He secured the grapnel to the port side of the forecastle at 61 m/200 ft. I dived next. I went to the bottom to confirm the depth, then ascended along the starboard side to the upper deck of the hull. The main deck was largely intact. I cruised aft until I felt that it was time to return to the anchor line.

I worked my way forward until I spotted the forecastle bulkhead. I started to enter the crew’s quarters but stopped when I spotted a flared brass bowl with a clapper inside: the ship’s bell!

From my book, Shipwreck Sagas: “It was mounted on a gooseneck davit that had fallen backward off the forecastle deck. After a brief examination, I determined that the bell was still secured to the davit, but that the davit was free and clear.

“I glanced at my gauges. To rig the bell properly and to send it to the surface on a safety line—so as not to lose the precious artifact in case the lift bag should deflate—would require more time than I thought prudent to spend, in consideration of the amount of air that remained in my tanks. I clipped a 45 kg/100 lb lift bag to the gooseneck as a territorial marker. I put enough air in the lift bag to hold it upright. Then I skedaddled for the anchor line…

“I asked Chatterton to go with me on the next dive. I did not need help in the recovery operation, but I wanted to let him share the experience of sending the bell to the surface. We planned our steps, then executed the recovery with clockwork precision.”

On the boat, I cleaned enough of the bell to read the name of the ship: Sebastian.

At home, when I searched through my extensive shipwreck files, I learned that I had annotated the Sebastian twenty years earlier. She was a twin-screw motor vessel built in Scotland in 1914. In 1917, she was transporting 4,058 tons of petroleum when she caught fire and had to be abandoned.

I had decided not to include the Sebastian in my Popular Dive Guide Series because the wreck was too deep! Depths that were considered too deep in the 1970s had become commonplace in the 1990s.

BowMariner

The Bow Mariner was a chemical tanker that exploded and sank off the coast of Virginia on February 28, 2004. Recreational divers commenced visiting the wreck as soon as the Coast Guard completed its investigation of the remains. After exploring the wreck on several trips, Harold Moyers organized an expedition dedicated to recovering the ship’s bell. The volunteer team for the May 16, 2004 recovery operation included Steve Gatto, Jon Hulburt, Bart Malone, Tom Packer, Joe Zeissweiss, and me.

The depth to the seabed was 77 m/250 ft. The bell rested on the forward mast where it hung from a steel post. I don’t want to make it sound as if the recovery was easy, but it was certainly less difficult than most similar operations. The lack of encrustation on the nut and bolt, which held the bell in place, enabled the use of household tools.

Each diver had a job to perform: securing the grapnel, rigging recovery and safety lines, unbolting the bell, inflating the lift bag, and so on. My job was photographing the bell and untying the downline after completion of the job. Teamwork functioned perfectly so that the bell was recovered exactly as planned.

Great Lakes

The wreck diving ethic in the Great Lakes, where freshwater preserves shipwrecks for longer than in seawater, is to take nothing but pictures. If it were not for this locally accepted tenet, I would not have had the opportunity to photograph relics that would already have been recovered—especially the ship’s bells in the following pictures.

The text and photos are from my book, Great Lakes Shipwrecks: a Photographic Odyssey.

Detroit

The most astonishing feature of the sidewheeler Detroit is the large bronze bell and its unusual placement: inside the engine support structure, between the apex and the piston platform. The wreck lies in 55m/180 ft in Lake Huron. After photographing the bell from a variety of angles, I rapped the clangor against the inside. The resulting ring was clear but possessed a pitch that was lower than normal, as if the vibrations were somehow altered by the density of the water or muted by the rubber material pressed against my ears.

“Novelty Works” was embossed on one side of the bell. “New York 1844” was embossed on the other side. The instant I read the embossing, I thought of John Ericsson’s Monitor, the Civil War ironclad, launched in 1862. The Novelty Iron Works built the Monitor’s turret.

In 2006, I received a phone call from Sergeant Jann Gallager, a law enforcement officer of Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources. She informed me that the bell had gone missing. She wanted permission to use my photos of the bell for a brochure to post around the area in an attempt to locate the culprits who absconded with the precious artifact.

I granted permission and told her that it was possible that the bell had broken free of its own accord and lay somewhere below and inside the wreck. However, another diver reported that the thieves cut a 1-inch-thick steel pin, thus enabling the bell to be recovered. And there the situation still stands today.

Florida

This wooden-hulled package freighter sank after collision in 1897 and lies in 60m/195 f in lake Huron. The hull is intact except for the collision hole—which extends through two decks in the midship cargo hold—and the demolished engine room in the stern. The railing is contiguous for nearly the entire length of the upper deck. The hull is constructed of wood, but the stem is protected by a metal shield on which the load line numerals are scratched.

The bell of the Florida is not adorned with the vessel’s name. However, the wreck was identified by its capstan covers, which not only display the name, but also the date of construction and the name of the shipbuilder.

Typo

This small, wooden-hulled schooner sank in 1899 and lies in 56m/185 f in lake Huron. As you can see, the surface of the iron bell is rusted, covered with silt, and sprinkled with zebra mussels. If any lettering exists under the obfuscating pall, I was unable to determine if there were any misspellings.

Note that biologists remain challenged by the coloration scheme of zebra mussels: are they white with black stripes, or black with white stripes?

Dive Deeper

aquaCORPS Pioneer Interviews: GARY GENTILE: DEEP WRECK DIVER by Michael Menduno (1991)

Books by Gary Gentile: Gary’s Book Store

Wikipedia: Gary Gentile

Enter the wild, exciting world of Gary Gentile: author, lecturer, photographer, explorer, and deep-sea wreck-diver. He has written 68 books, published more than 4,000 photographs, discovered more than 40 shipwrecks, and led a life of adventure. He was the first scuba diver to enter the First Class Dining Room of the Andrea Doria, and he discovered and recovered a number of Italian artist Romano Rui’s ceramic panels that once adorned the walls of the First Class Bar.

In the early 1990s, Gary was instrumental in merging mixed-gas diving technology with wreck-diving. His dive to the German battleship Ostfriesland, which lies at a depth of 380 feet, triggered an unprecedented expansion in the exploration of deep-water shipwrecks, and the advent of helium mixes as a breathing medium. He wrote one of the first books on technical diving.

Gary has specialized in wreck-diving and shipwreck research, concentrating his efforts on wrecks along the eastern seaboard, from Newfoundland to Key West, and in the Great Lakes. He has either discovered or been the first to dive on scores of previously unknown shipwrecks. Over the years, he has rescued from the ravages of the sea many thousands of shipwreck artifacts, making him a leading authority in recovery techniques. He has gone to great lengths to preserve and restore these relics from the deep, and to display them to thousands of divers and non-divers alike. Throughout the years, these artifacts have been displayed at various museums, symposiums, and club-oriented exhibitions.