Diving Safety

Standard Gases: The Simplicity of Everyone Singing the Same Song

Like the military and commercial diving communities before them, Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) uses standardized breathing mixtures for various depth ranges and for decompression. Here British wrecker and instructor evaluator Rich Walker gets lyrical and presents the reasoning behind standard mixes and their advantages, compared with a “best mix” approach. Don’t worry, you won’t need your hymnal, though Walker may have you singing some blues.

by Richard Walker. Header image by Derk Remmers. Images courtesy of GUE unless otherwise noted.

🎶🎶 Predive Click: “Sunday Morning” by Maroon 5

In 1990, Pam Tillis released a track called “Don’t Tell Me What To Do.” I tried listening to it, but neither country nor western are my thing. I always preferred a song with a similar but harsher sentiment from Rage Against the Machine, but sadly the editor won’t print the words. [Ed.note: No f*** way!]

Anyway, What has this got to do with technical diving?

Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) is perhaps best known for its standardised approach to equipment configuration. You know, where those mean GUE divers force you to dress a certain way just so you conform to the fashion. But then you discover that it all has some sort of logical reason, and the more you fight it the more it makes sense.

“Fight the Power,” right?

Well, you may have heard that GUE also forces you to breathe only certain gases. Obviously this is just to make your diving more expensive, increase your training needs, and the like.

NWA said it best, but I can’t print that either!

Most divers get started by breathing the most famous standard gas of all—air—and nobody objected to that back in the day. When we dive air, we actually begin to see some of the benefits of a standardised system. Breathing the same gas on every dive means that we start to develop a familiarity for our no-stop times and any decompression requirements. Most experienced divers are familiar with the “120 rule” where your bottom time plus your depth in feet should remain lower than 120 to stay inside the no-stop times.

Lynyrd Skynyrd explained it when they sang “Simple Man.”

Who can deny that, when breathing air, we are rarely concerned that our buddy might be breathing different gases requiring a different decompression profile or a different maximum operating depth? It’s simple and it works.

These advantages of air come at a cost. Every diver is a bit different, but it’s generally accepted that mental performance is reduced—potentially to the point of narcosis—beyond 30 m/100 ft. In the shallower ranges from 20-30 m/70-100 ft, the no-stop time gets quite short as well.

A Best Mix?

Nitrox was developed for the sole purpose of increasing no-decompression times and/or decreasing decompression obligations. In the early days, two gases were promoted: 32% and 36%, but the dive community soon came up with the concept of “best mix.” This is what nitrox courses frequently teach today. You pick the depth that we are going to be diving, and work out the “perfect” gas for that dive to make the no-decompression time as long as possible.

However, if you were to put three nitrox divers in a room and ask them to choose a gas for a 24 m/80 ft dive, you’d likely get four different suggestions. They’d all probably work just fine on that particular dive for the individual diver.

Van Morrison told us to “Keep It Simple,” and he was right.

We’ve lost something from the days of air diving. That familiarity with no-decompression times has gone—there is no 120-rule for a best mix. When your friend calls you and tells you to show up for a dive, how do you choose the right gas for the dive to ensure you’re all on the same gas? One says 30%, the other 28%. Who’s right, which one is best?

One Direction released a track called “Best Song Ever.” There is no such thing. Best mix can be considered in a similar vein.

When John Lennon released “Imagine,” he was singing about an idea where the world lived in harmony. I don’t think he was really talking about technical diving, but the sentiment holds true. Standard gases help us remember the flexibility, familiarity, and simplicity of air, but we also retain all of the benefits of using mixed gases to increase no-decompression limits, reduce narcosis, and manage our exposure to oxygen. We do this by creating depth ranges for a small number of breathing gases, and if the dive is in that range, then the whole team uses this gas.

If the depth ranges are wide enough, we end up with a very flexible tool that gives us the simplicity and familiarity back. It allows the use of “rules of thumb” for things like decompression planning (See: Rules of Thumb: The Mysteries of Ratio Deco Revealed), oxygen exposure management, and even gas blending. And everyone’s singing the same song!

On to Standard Gases

There’s really nothing clever about the standard gases concept—using a single gas to cover a range of depths instead of a gas that is optimized for a single depth and typically a single parameter of the dive (usually decompression). Here’s how they look:

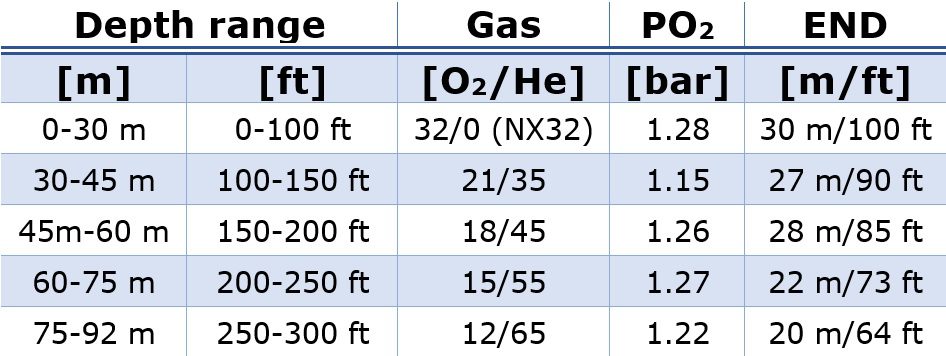

Standard Bottom Gases

GUE standard gases are designed to maintain a maximum PO2 of 1.2-1.3 bar for the working portion of the dive and an equivalent narcotic depth (END) ≤ 30 m/100 ft. PO2s are then boosted during ascent to a maximum of 1.4 bar for deep decompression, and 1.6 for 6m/20 ft decompression, using standard deco mixes. Note: standard gases are used for open circuit and closed circuit diluent.

The maximum PO2 promoted outside of GUE is normally around 1.4 bar for the working phase of the dive. There’s likely nothing wrong with that, but you are starting to get close to a pretty unpredictable zone. The higher the PO2, the higher the likelihood for Central Nervous System (CNS) toxicity. GUE prefers that the limits be more flexible than a Maximum Operating Depth (MOD)—who can forget the days when nitrox course students were told that if they hit 1.41 bar they would surely burst into flames, but 1.39 bar was perfectly safe? That doesn’t seem right, does it?

“I’m on Fire!” said Bruce [Springsteen].

GUE’s approach is to make the depth range of a standard gas in the 1.2-1.3 bar range for the working portion of the dive. The idea that a diver will know, at the limit of the gas, that the PO2 is climbing toward a more risky level. However, if you drop below that depth for a short time, there will not be any serious consequences. Picking up a dropped camera, helping a dive buddy, or simply being less than perfect with your buoyancy control will not result in a dangerous oxygen exposure. [Ed.note: The US Navy specifies a maximum setpoint of PO2=1.3 bar for closed circuit dives].

The gases also limit the Equivalent Narcotic Depth (END) to approximately 30 m/100 ft. At that depth one can think clearly and solve most problems if one slows down and concentrates. But, the further one goes past this depth, the more difficult it becomes to solve simple problems correctly.

When I get to this depth on a nitrox mixture, a strange thing happens. This little guy appears on my shoulder and starts whispering ideas in my head. Ideas that change the dive plan. Ideas that seem fantastic at the time. I used to listen to him and things would never go well. I’d not get the survey data, I’d fail to attach the shot line to the wreck as planned at the surface, and small stuff like that. I’ve learned to ignore him, because he’s an idiot. Unfortunately, at around 36 m/120 ft, he becomes a lot more persuasive, and I get weaker. His suggestions make even more sense, so I tend to follow them. I’ve never learned to ignore him at this depth. The only solution I’ve found is to make sure my END is never more than 30 m/100 ft.

Nirvana sang “Dumb”. Becoming so is not an instruction, and it’s entirely avoidable!

These gases give a lot of flexibility across their range. If you drop your camera when you’re at 45 m/150 ft and need to drop to 50 m/165 ft to retrieve it, then it’s not likely to cause a problem. If you used 21/35% for a 40 m/130 ft dive, the no-decompression limit would be 10 minutes, but if you used a “best mix” of 28/35, then your limit would be 11 mins. If you did a more realistic bottom time of 30 mins, and used a 50% nitrox for decompression, then the two schedules would only be 4 minutes different.

What “Difference Does it Make?” as The Smiths once sang.

Here’s a final advantage of using these particular standard gases. If you are lucky enough to have banks of 32% nitrox, then you can create all of the other standard gases by adding 32% onto the required amount of helium. So, to make a 21/35, you would take an empty set of cylinders and fill to 35% of their final pressure with helium. Then you add 32% and, lo and behold, you have 21/35. Same idea for 18/45, 15/55, and so on. Got half a set of doubles of 15/55 left over? Blow it with 32%, and you’ll get a 21/35. And that’s where efficiency comes in. You can use every last drop of your expensive helium in a pretty easy manner using 32% as a filler gas.

Easy, like “Sunday Morning.”

GUE also standardised their decompression gases, but that’s another playlist.

Dive Deeper

InDepth: Rules of Thumb: The Mysteries of Ratio Deco Revealed by Richard Walker

InDepth: Rules of Thumb 2: Further Mysteries of Ratio Deco Revealed by Richard Walker

Alert Diver: Anatomy of a Commercial Mixed-Gas Dive by Michael Menduno (2018)

InDepth: Oxygen Exposure Management by Dr. Richard Vann (1994)

Alert Diver.Eu: Rapture of the Tech: Depth, Narcosis and Training Agencies by Michael Menduno (2020)

Rich Walker learned to dive in 1991 in the English Channel and soon developed a love for wreck diving. The UK coastline has tens of thousands of wrecks to explore, from shallow to deep technical dives. He discovered GUE in the late 1990s as his diving progressed further into the technical realm, and he eventually took cave training with GUE in 2003. His path was then set, and he began teaching for GUE in 2004.

He is an active project diver and is currently involved with: the Mars project, Sweden; Cave exploration team in Izvor Licanke, Croatia.; Ghost Fishing UK, Chairman and founder. He is also a full time technical instructor and instructor evaluator with GUE, delivering these services via his company, Wreck and Cave Ltd. He sits on GUE’s Board of Advisors and serves several other industry organizations. He also knows his music!