Latest Features

Surviving an Uncontrolled Ascent

What do you do when your power inflator sticks open at depth, you’re unable to disconnect it, and unable to reach your right post to shut it down because of an overinflated wing? That’s the question tech diver Maureen Roberts found herself grappling with as she began accelerating towards the surface 26 m/120 f above.

By Maureen Roberts

Header image courtesy of Julian Mühlenhaus

On Saturday, September 11, 2021, I was on a shore diving trip with friends in Carmel-By-The-Sea, California, when I experienced a runaway power inflator and an uncontrolled ascent to the surface on a technical dive.

I finished my Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) Technical Diver 1 course in December 2019, but didn’t dive much during the first part of the pandemic. Now vaccinated, I was diving again, but I still only had 18 tech dives. I took the GUE DPV Diver 1 course in May 2021, and had 20 scooter dives by the time of the trip.

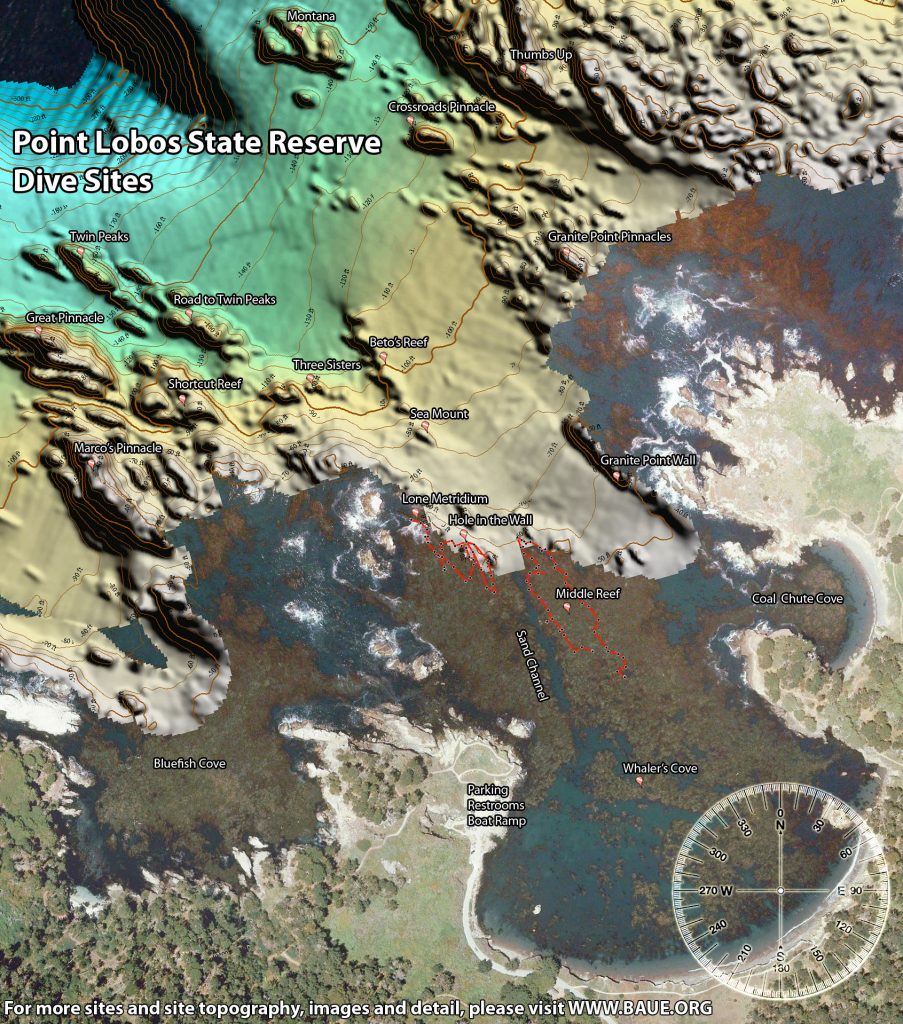

We planned to do tech dives using diver propulsion vehicles (DPVs) at Point Lobos in a team of three. Our first dive would be a scooter run out to Montana, max depth of 46 m/150 ft, and the 2nd dive to Beto’s reef, max depth of 36 m/120 ft. We discussed the need to avoid surfacing at the deeper parts of the dive if we became separated, due to surface currents in that area. The plan was to scooter back to shallower depths and the protection of the cove before surfacing.

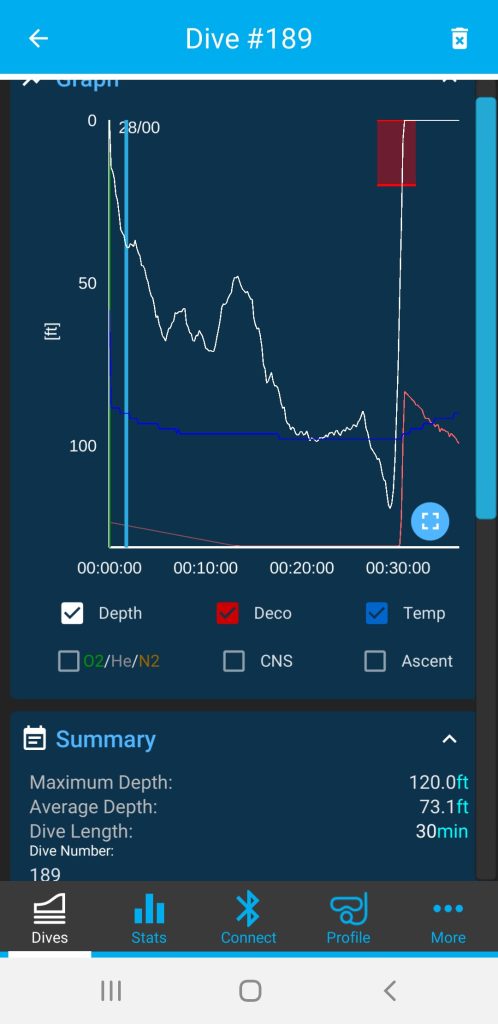

We exited the water in high spirits after the first dive. We had some lunch and then got ready for the second dive. On the second dive, I was Diver #3, and Diver #1 was navigating. We planned for an average depth of 30 m/100 ft and a maximum depth 46 m/120 ft and decompression on 100% oxygen (O2).

The first part of the dive was uneventful and picturesque. We were treated to about 15 m/50 ft visibility and a lot of different marine life than we usually see in southern California (SoCal). I was happy to see so many varieties of starfish, which have become rare in SoCal. As we reached the farthest point out on our dive, 29 minutes runtime, I fell about 3 m/10 ft behind Divers #1 and 2, who were wing on wing. I had just looked at my dive computer, and I saw our depth at 46 m/120 ft, and a deco time of one minute.

I was adjusting buoyancy, and added a little gas to my wing. When I pressed the inflator, it gave a wimpy puff, almost like I’d pressurized my regs and then turned them off during a pre-dive check, and puffed the last little bit of gas into the wing. I added a puff of gas to my drysuit to alleviate some squeeze, then returned to the wing inflator, thinking, “Hmm.” As I pressed it, the button stuck down and my wing began to rapidly inflate.

It All Looks Up To Me

For a few seconds, I tried to unstick the inflator button, but it didn’t budge. I reached for my right valve with my right hand (dropping the scooter handle) and my butt dump with my left hand. I felt myself rising and I realized I could not reach the right post because my wing was so full. My wing’s overpressurization relief valve (OPV) started to dump and bubbles began to obscure my vision. The other divers were now about 6 m/20 ft away, and I was rising above them. I screamed to them through my regulator, but we were all wearing hoods in the cold water, and that plus the hum of their scooters drowned me out.

The gas in my drysuit was expanding as I ascended, and I went to a more vertical position of about 45 degrees and vented my drysuit while I tried to disconnect the inflator hose. I wasn’t able to disconnect it. My hands were cold and I was wearing dry gloves with thick undergloves. At that point, I had risen about 6-9 m/20-30 ft, and I was accelerating. I had gone from “What is happening?” to “I will handle this,” to “Oh my God, I’m going to the surface!” in just a few seconds. I reached back again, trying to get to the right post, but my wing was very full, it was impossible to turn the valve, and I was starting to feel squeezed by the wing.

As my drysuit inflated, I even tried to claw open the neck seal to flood it, but I couldn’t get my fingers underneath my hood. I had a brief moment of wondering if this was going to be how I die, but my brain was constantly telling me to try something else as each thing didn’t work.

My vision was now completely obscured by bubbles from the wing’s OPV, so I could not tell if my teammates saw what was happening. I suspected they had not. Then it became very bright, and I was on the surface. The entire ascent lasted only 90 seconds.

My wing was still massively inflated, squeezing me and dumping out the OPV. I couldn’t reach the right valve on the surface, either. I tried again to get the inflator hose disconnected, but I couldn’t. Simultaneously, I was trying to get my bearings toward the shore. I had surfaced at the exact farthest point of our dive. The thought of the currents we had discussed crossed my mind. I squirmed around trying to get the right post shut off, while I studied the shoreline to make sure I knew where I was. I wanted to try to descend again, but I couldn’t get the wing to stop inflating. I switched to my 100% O2 and clipped off my primary regulator.

After a few minutes of struggling, I was finally able to simultaneously dump the wing and roll the post off by degrees until it was off. Then I was thankful to dump some of the gas from my wing and relieve the squeeze it was putting on my chest. I was surprised to find I still had 2000 psi/138 bar in my double 100s/12 liter. I had about 2500 psi/172 bar when my ascent began.

At that point, more than five minutes had elapsed, and I was not sure whether to descend or not. I looked at my computer, noted the 93% surface gradient, and that it said rapid ascent and missed deco stop. I realized that I had more of a rapid ascent than missed deco, and given that and the length of time already on the surface, I decided not to descend. I kept taking a mental inventory of myself and looking for anything wrong, but I felt physically okay, just a bit shaken up. I told myself, “You are okay” a few times. I wanted to be out of the water, though.

I started to scooter toward the entry point, and for a while I couldn’t tell if I was making progress. I didn’t want to have to be rescued. I decided to scooter until my batteries died, and if I didn’t make it in, then I would go to Plan B. I have a personal locator beacon (PLB) on my harness. I hoped I wouldn’t need it. I should have inflated my diver surface marker buoy (DSMB), but I honestly didn’t think of it. At that point, I didn’t want to summon anyone from shore, yet. But it could have helped my teammates see me if they were on the surface, even though the ocean was relatively flat.

Finally, I could see that I was making progress to shore, despite whatever surface current there was. I felt relief and wondered what my teammates were doing. Had they already exited ahead of me? I didn’t think so, because I didn’t see any commotion on shore. I assumed if they got out without me, the people on shore would have looked like they were looking for someone in the water.

Toward the exit, there was thick kelp on the surface and I made the mistake of heading into it rather than taking a circuitous route. I stopped and had to disentangle myself a couple of times, and then I finally decided to descend to about 1.5 m/5 ft to get through. I was aware of the need not to struggle or exert myself.

The Aftermath

Once I got through the kelp and onto the exit ramp, I saw some of my friends there, hanging out after their dives. One of them, not initially realizing there was a problem, came to help me with my deco bottle and DPV. I slowly removed my fins and started to walk out, wondering how to explain myself. I said, “I’m not okay, I had a rapid ascent, can you bring the O2 to me, and can someone look for the other divers?”

I sat on a bench and someone brought my O2, which I breathed on and off as I described what happened. Someone else brought me some water, and I drank that and tried to be calm. I was now very anxious to see my teammates. I knew that being together, they were probably fine, but I just wanted to see them. Some of my friends went to look for them over the cliffs, and some awkwardly wandered around, loading their cars or checking gear. A couple of people asked if I was experiencing any physical symptoms. I said no.

Suddenly, I was all by myself on the bench with my O2 and some water, and I felt very alone and just drained. I wished someone would sit next to me and maybe just put a hand on my arm. I kept thinking how, if that had occurred later in the dive or on the first dive, I could have been badly bent or killed. I wondered if I would ever dive again. I kept remembering the exact moment that I realized I was going to the surface, and the fear that I felt, and how I screamed for my teammates but they did not hear me.

After what seemed like a long time, someone said they had spotted the other divers and they were coming in. I could see the ramp and watched my two teammates get out and walk to their cars to gear down. I wondered if they were mad at me. Once they were free of their tanks, they came over and I explained what happened. I was so relieved to see them.

They had looked back, seen that I was missing, and searched for me underwater for 15 minutes, concerned my scooter may have died and I was kicking back to shore, or that I had become lost, or worse. They incurred a deco obligation during the search, and then surfaced closer to shore than I had. Underwater, they had debated whether to surface earlier or to keep looking underwater. Although it seemed like it took me a long time to get squared away and get out of the water, I had already gotten out when they came to the surface.

At that point, I still felt fine, so I continued to breathe my O2 on and off, and my teammates loaded my gear into the car for me. Once we were ready to leave, I called Divers Alert Network (DAN) and told them my story. The startling reality of what I’d just experienced became evident when the DAN volunteer asked me how long since I surfaced and I said “about 20 minutes.” I then noted that my dive computer said 1 hour 33 minutes! DAN recommended I monitor myself for symptoms but did not recommend I be evaluated at the ER since I felt fine and hadn’t officially missed deco, just had a rapid ascent.

Later, we examined my gear. With the regs pressurized, it was very difficult to disconnect the low pressure (LP) inflator hose, even on land with dry hands. We removed the inflator and the LP hose and replaced both with a new one.

I had a long talk with my teammates and I called my instructor/mentor. I couldn’t decide whether to dive the following day or not. My teammate, Diver #1, told me to sleep on it. The next morning I decided to do the dive we had planned originally, a 52 m/170 ft tech dive to Twin Peaks. We decided to go in a team of two, starting the dive with another team of three. We agreed we would take things slowly.

The dive felt fine. I knew once I was in the water that it was the right decision to get back on the proverbial horse. We had a pleasant dive and then I called it a day, waiting in the sun while the others did a second dive.

Figuring Out What Went Wrong

When we arrived home, I took my malfunctioning inflator to the dive shop to examine it and see if we could determine what went wrong. They serviced my inflator, but it still leaked when we hooked it up to a new hose and tank. I had previously been told, “Don’t service LP inflators, just discard them.” I had ignored that good advice and serviced the LP inflator about 30 dives prior to the incident. It seemed to work fine, until it didn’t.

After each dive day, I soak my gear in hot water in the bathtub overnight. The LP inflator was about four years old. The hose was about five years old. It just wasn’t a style that was easy to remove when pressurized. I never realized that some LP inflator hoses are easier to remove than others. Now I have a new, easier-to-remove LP inflator hose and a new power inflator.

My teammates and I talked about the events of this dive many times over the following days. I will be more diligent in not falling behind when scootering, and if I need the others to slow down for me, I will ask them to.

Diver #1 and I subsequently went on a skills dive together to practice runaway inflator management. We found that consistently dumping from the butt dump while kicking down, we could arrest the ascent and stabilize in the face of a stuck inflator. Once stabilized, we were able to easily shut the right post off and switch to our backup regulator. Once the right post had been purged, the LP inflator hose was easy to disconnect. I tried a different strategy of going vertical and dumping gas from the corrugated hose while trying to disconnect the LP inflator (rather than using the butt dump and shutting off the right post) but found that I ascended more quickly using that method. I was glad that we practiced the stuck wing inflator because I hadn’t practiced it before. Now I feel confident that I could manage a stuck inflator.

At the time of my incident, I wasn’t as committed to dumping from the OPV as I should have been. Once the OPV started to auto-dump, I didn’t continue to dump it myself. That may have made a difference and given me the ability to dump enough gas to reach the right post.

We are always told “Stop, breathe, think, act,” but in this case, I didn’t have time to do that. It was “act, act, act, oh no I’m at the surface.” A lot of the things I did were automatic and I didn’t even think about them. Some folks have asked me if I could have cut my wing with my knife, or scootered straight down, or kinked off the LP inflator hose. I didn’t have time to think of those things; besides, I had dropped my scooter handle as soon as I tried to reach the right post.

I plan to remember this dive by checking the dates on all my gear every year on September 11. I’m going to start replacing LP inflators annually, and hoses every 3 years.

I think perhaps the most pragmatic take on the incident was from my T1 teammate (who was not present). When I told him the story, he said “Replace both the inflator and the hose. You’ll be fine, it’s just an incident. Shit happens.”

Dive Deeper:

The Human Diver: The Debrief

Diver Alert Network: Diving Incident Reporting System

DAN South Africa: One mistake and you are dead – isn’t how accidents normally happen!

Alert Diver.eu: A Behind The Scenes Look Into The Making of “Close Calls”

Forty-four year old Maureen Roberts is an emergency veterinarian based in Pasadena, California and has been diving since 2015. She received her GUE Tech 1 certification in 2019 and her DPV 1 in 2021. She says she likes black jelly beans.