Exploration

Extending The Envelope Revisited: Correcting The Record of the 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives

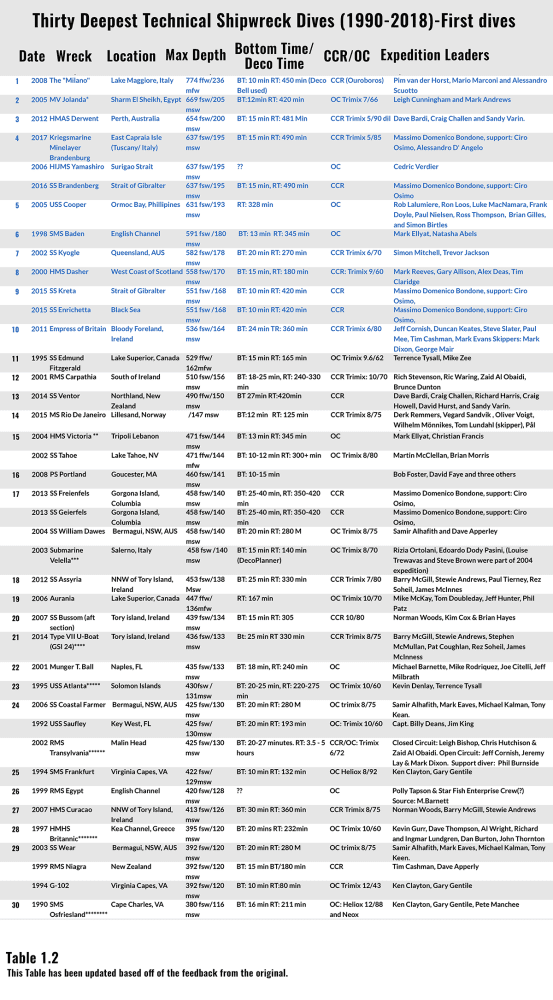

Thanks to our readers, I was able to update the chart of the now 30 deepest tech shipwreck dives (as of 2018), adding 17 wrecks that were not on the original 20 deepest shipwrecks list. Note that I also extended the list to the 30 deepest wreck dives from the original 20.

By Michael Menduno

This article and the original have been superseded by, “Extending The Envelope Revisited: The 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives.”

Thanks to our readers, I was able to update the chart of the now 30 deepest tech shipwreck dives (as of 2018), adding 17 wrecks that were not on the original 20 deepest shipwrecks list. Note that I also extended the list to the 30 deepest wreck dives from the original 20.

Ironically, the original list left off the deepest shipwreck dive, that being the Milano lying at a depth of 774 ffw/236 mfw in Lake Maggiore, Italy, conducted by Pim van der Horst, Mario Marconi, and Alessandro Scuotto in 2008. Deep diving pioneer Nuno Gomes was a consultant and witness on the dive.

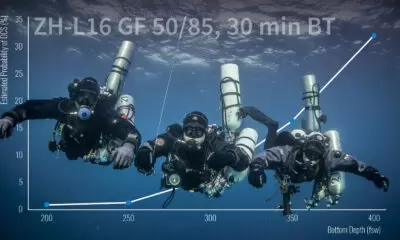

The average depth of the 10 deepest wrecks as of 2018 was 576 ft/176 m, a full 229 ft/70 m deeper than the average of the 10 deepest wreck dives from the 1990s. The average bottom time was 15 minutes (compared to 16.7 minutes in the 1990s), but the average runtime was 374 minutes (6 hours and 14 minutes), more than double the average of 185 minutes of runtime (3 hours and 5 minutes) from the 1990s. None of the 10 deepest dives from the 1990s made the deepest 10 when viewed from today.The average bottom time was 15 minutes (compared to 16.7 minutes in the 1990s), but the average runtime was 374 minutes (6 hours and 14 minutes), more than double the average of 185 minutes of runtime (3 hours and 5 minutes) from the 1990s. None of the 10 deepest dives from the 1990s made the deepest 10 when viewed from today.

Also, I’d like to make a note on depth, which shipwreck explorer Mike Barnette brought to my attention. The depths listed on the table should be considered as relative metrics. In most cases, the depth indicates the depth at the bottom of the wreck. In some cases, divers actually dived to the bottom. In other cases, the depth indicates the depth that divers actually reached. In other words, the depth numbers are a bit fuzzy.

Also interesting, 9 of the 13 wreck dives in the deepest 10 today (some shipwrecks were at the same depth) were conducted on rebreathers vs. four on open-circuit scuba. All 10 of the deepest shipwrecks in the 90s were conducted on open circuit.

Sincere apologies to Massimo Domenico Bondone and teammate Ciro Osimo for leaving out their important accomplishments. The amazingly prolific Bondone and team accounted for 6 of the dives in the 20 of the 30 deepest shipwrecks! Wow! He is followed by Irish tekkie and photographer Barry McGill, his colleague Stewie Andrews, and their various teams who were responsible for three of the deepest dives shown on the table, as were Ken Clayton and Gary Gentile (from the 1990s).

Apologies also to Rizia Ortolani and her teammates Edoardo Dody Pasini, and later Louise Trewavas and Steve Brown, for leaving out their 2003/2004 dives on the submarine Velella, located near Salerno, Italy. Ortolani’s 2003 dive set the then record for the deepest female shipwreck dive, as featured on the cover of Trewavas’ Dive Girl magazine, issue 13, in 2004.

She may still hold the record (does anyone know?).

Note that we corrected and have expanded the original accompanying footnotes with the chart. One correction to the original: Terrance Tysall and Mike Zee’s 1995 dive on the Edmund Fitzgerald (529 ffw/162 mfw) was NOT a sneak dive. The pair obtained a permit, but it did not allow them to tie into the wreck. They ended up using the drop camera umbilical as a downline, and left a plaque on the “Fitz” to commemorate the sailors that were lost. They were only able to make a single dive due to the weather.

The HMS Britannic is now the 28th deepest wreck dive as viewed from today, the SMS Ostfriesland (380 ft/116 m) dived by Clayton and Gentile in 1990 on heliox and neox is now the 30th deepest. Not on the chart was wreck #31, the Princess of The Orient (377 fsw/115 m) in Manilla Bay, Philippines, reportedly first dived in 2000 by John Bennett and Ron Loos.A team led by Karl Hurwood with GUE instructor Ali Fikree recently completed the first circumnavigation of the 640-ft/195-m- long wreck in April 2018 with 30 to 35-minute bottom times at 115 m, and 285-minute runtimes. As I have said before, we are an extraordinary tribe!

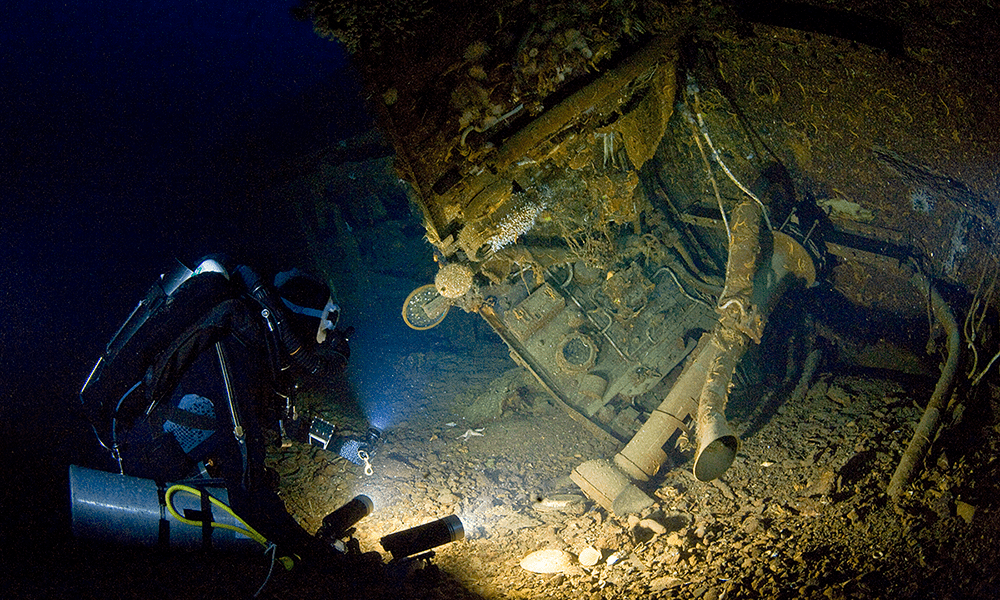

Top Image: HMS Curacoa Bridge – Diver: Stewart Andrews, Photo by Barry McGill.

Top 10: Average depth: 576 fsw/176 msw, Avg. Bottom Time: 15min, Avg. Run Time: 374 min

*The Jolanda sits vertically from 70-150 msw. According to M. Ellyat, Gregory ‘Banan’ Dominik found and dived the deep bit of the Yolanda in Sharm 3 years before Mark Andrews and Leigh Cunningham.

** According to M. Ellyat When he found the Victoria in 2004 it was almost intact in 156m. Subsequent dynamite fishing has blown the inner decking down to the seabed making it appear 144m.

***Rizia Ortolani set the then Deep Wreck Female record on this dive.

**** Scuttled in Operation Daylight, Operation Deadlight Type VII.

*****Denlay & Tysall’s first dive in 1995 was to 361 fsw/110msw on the shallow stern of the Atlanta. They returned in 1997/98 where they made their deepest dive to the bow.

****** The wreck had been dived previously in September 2000 by Richie Stevenson, Chris Hutchison and Dave Greig but only as a bounce w/ 2 min bottom time. Subsequent dives with BT: 15 min were made with Trimix 14/54. The team deco’d in a bell. Greek commercial diver Kostas Thoctarides followed Cousteau in 1995 making a solo 20-min dive, and returned in 2001 with a submersible.

********Clayton dived Neox mix (O2 and Ne) for their last dive on Ostfriesland to 340 f/104 m with 20 min BT.

Michael Menduno is InDepth’s executive editor and, an award-winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine “aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving”(1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving. He also produced the first Tek, EUROTek, and ASIATek conferences, and organized Rebreather Forums 1.0 and 2.0. Michael received the OZTEKMedia Excellence Award in 2011, the EUROTek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012 and the TEKDive USA Media Award in 2018.