Exploration

Extending The Envelope Revisited: The 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives

The advent of mixed gas usage by sport divers—the so-called “Technical Diving Revolution”in the early to mid-1990s—greatly expanded our underwater envelope, while arguably improving diving safety. In order to appreciate how far, err, deep, we have collectively come, we thought it would be illustrative to contrast the deepest tech shipwreck dives today with those in the 1990s when technical diving was just getting started. InDepth chief Michael Menduno has the deets.

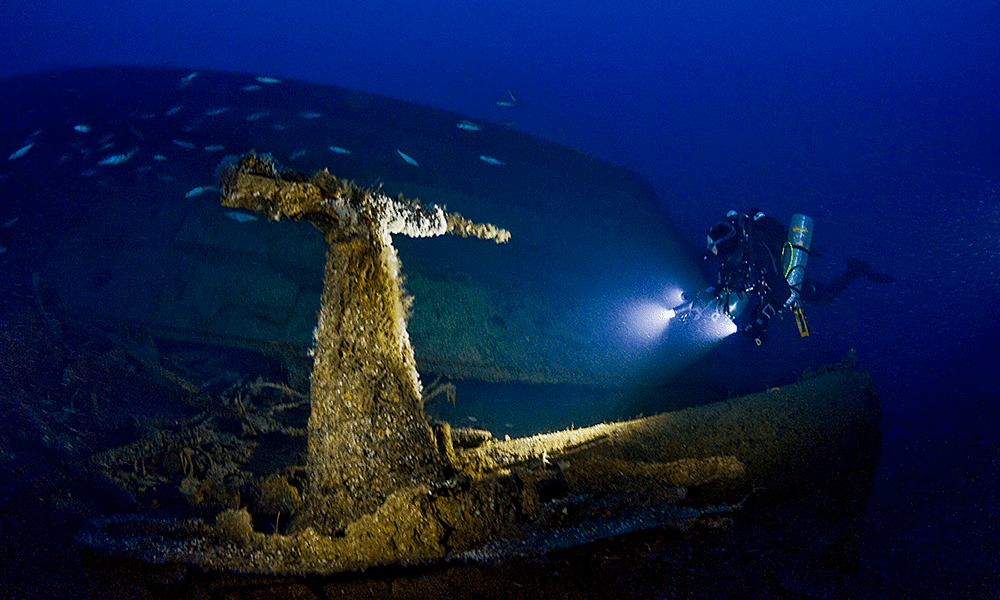

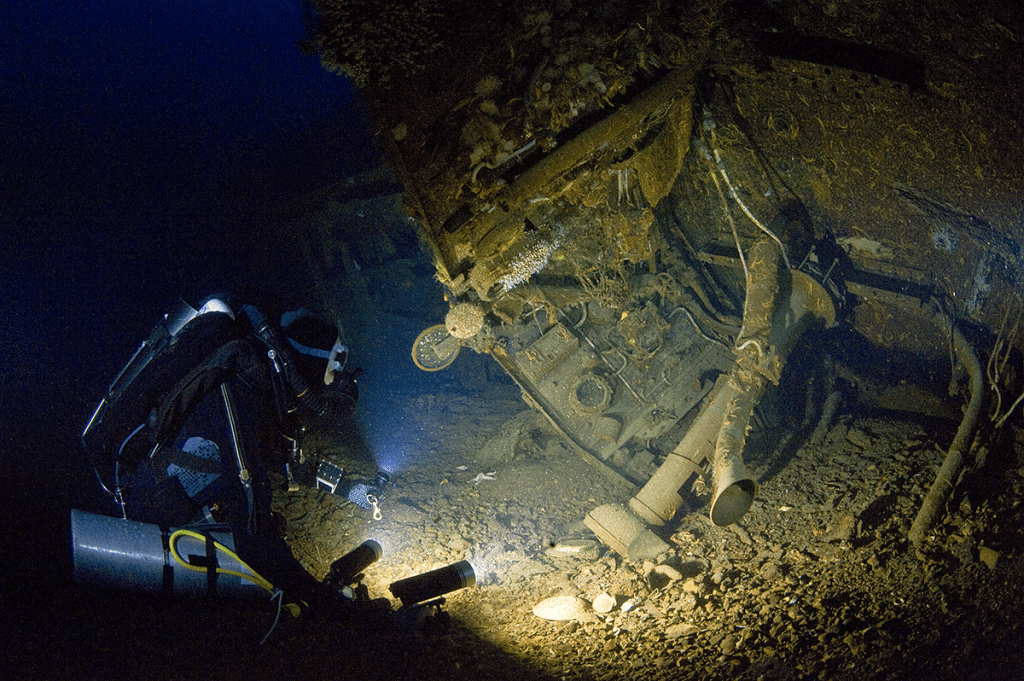

By Michael Menduno Header photo by Barry McGill

The advent of mixed gas usage by sport divers—the so-called “Technical Diving Revolution”—in the early to mid-1990s greatly expanded our community’s underwater envelope, while arguably improving diving safety.

In order to appreciate how far, err deep, we have collectively come, I thought it would be illustrative to contrast the deepest tech shipwreck dives today from those in the 1990s when technical diving was just getting started.

Back in the early to mid-90s, technical diving pioneer Capt. Billy Deans, owner of Key West Diver observed that mix technology enabled us to “double our underwater playground.” Deans was contrasting the then existing recreational diving limits i.e. No stop dives to 130 ft/40 m to the new technical diving envelope that was made possible with the use of helium-based bottom gas and accelerated decompression using nitrox and oxygen. Note that during this period, the words Deep (beyond 40 m) and Decompression i.e. “The D-words,” were considered four-letter words by many in the recreational diving establishment.

At the time, we considered open water decompression dives with 15-25 min of bottom time to depths of 260 ft/79 m to represent a reasonably safe envelope for mixed gas tech dives, hence Dean’s comment about doubling of our recreational playground. Because of the ability to more easily stage bailout and decompression gas in the cave environment, the envelope there was considered deeper/longer. That is not to say that tekkies weren’t diving deeper than 260 ft/79 m and staying longer, but at that time, we considered these dives as “exceptional,” requiring special methods and work.

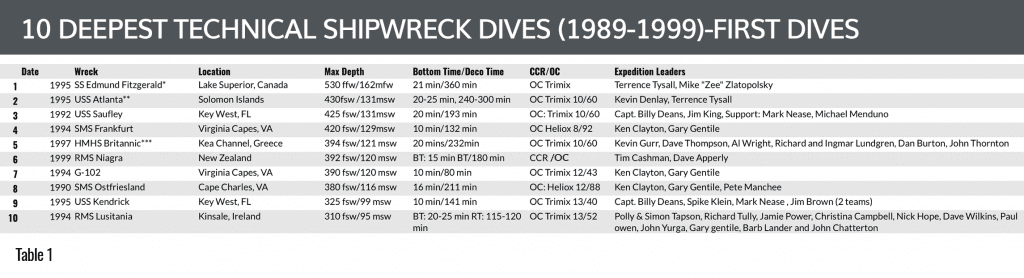

Deep Shipwreck Dives in The 1990s

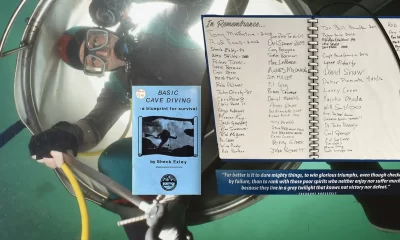

The first table (below) highlights the ten deepest tech wreck dives from 1989-1999, including the location, depth, dive profile, technology used and the technical divers who first dived the wreck in question. The majority of these dives was reported at the time in my magazine aquaCORPS Journal.

The deepest tech shipwreck dive at the time was on the Edmund Fitzgerald lying in 530 feet (162 meters) of fresh water in Lake Superior the equivalent of 514 ft/157 m of sea water. The shallowest was the RMS Lusitania near Kinsale, Ireland at 310 ft/95 msw.

Note that the depths listed in both tables should be considered as relative metrics. In most cases, the depth indicates the depth at the bottom of the wreck. In some cases, divers actually dived to the bottom. In other cases, the depth indicates the depth that divers actually reached. In other words, the depth numbers are a bit fuzzy.

There are several observations to be made. First, all of these dives but one, were conducted on open circuit scuba. At the time literally, only a handful of technical divers had rebreathers, which were either modified Carleton Mk 15.5s, Dr. Bill Stone’s handmade Cis-Lunar rebreathers, the Halcyon PVR-BASC semi-closed rebreather aka “The Fridge,” the predecessor of the RB80, or various prototypes. AP Diving’s Inspiration, the first production rebreather, wouldn’t be released until 1997. In the case of the RMS Niagara (392 ft/120 m), Tim Cashman and Dave Apperly were using rebreathers made by Apperly. Though mixed gas technology was a necessary precursor, rebreather usage would not hit its stride for another decade.

Two of the dives shown on the chart, the SMS Frankfurt (420 f/129 m) dived in 1994, and the Ostfriesland (380 f/117 m) dived in 1990, were conducted by wreck diving pioneers Ken Clayton and Gary Gentile on heliox. Clayton also dived an experimental Neox mix (02 and Ne) for their last dive on Ostfriesland to 340 f/104 m with 20 min BT.

In 1989, the Clayton, Gentile and their team also conducted a deep air dive, with air decompression—can you imagine??—on the USS Washington (290 ft/89 m), which would have been #11 in the 1990s table. Ironically, though cave divers quickly embraced “special mix” technology, the majority of dedicated U.S. Northeast wreck divers were slow to adopt mix technology to replace their deep air diving though they did add oxygen and or nitrox for decompression.

In terms of divers, Terrence Tysall, now the training director for National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI), made the two deepest dives on the list in 1995, first on the Fitzgerald in 1995 with Mike “Zee” Zlatopolsky, and then on the Atlanta with Aussie pioneer Kevin Denlay.

Though the rumor was that Tysall and Zee had made a “sneak dive” on the Fitzgerald which was a grave site, the two were able to obtain a permit, but it did not allow them to tie into the wreck. They ended up using the drop camera umbilical as a downline, and left a plaque on the “Fitz” to commemorate the sailors that had been lost. However, they were only able to make a single dive due to the weather.

Clayton, Gentile and their teammates accounted for three of the ten deepest wrecks while Gentile was involved with four of 10, and Deans and his team accounted for two dives on the list. Note also that British tekkie Polly Tapson, one of the first female tech expedition leaders, and her team Starfish Enterprise captured the imagination of the community at the time with the preparations and their successful dives on the “Lucy” in 1994.

Three years later, British tech pioneer and inventor Kevin Gurr launched the first technical expedition on the Britannic with Dave Thompson, founder of JJ CCR, Al Wright, Global Underwater Explorers’ (GUE) Richard Lundgren, his brother, photographer Ingmar Lundgren, photographer Dan Burton, and British tekkie John Thornton. Of course, the wreck was first discovered and dived by Jacques Cousteau and his team in 1976, see footnote.

In terms of depth, the average depth of these 1990s wrecks is 389 ft/122 m average bottom time: 16.7 min, and average run time: 192 min or just more than three hours.

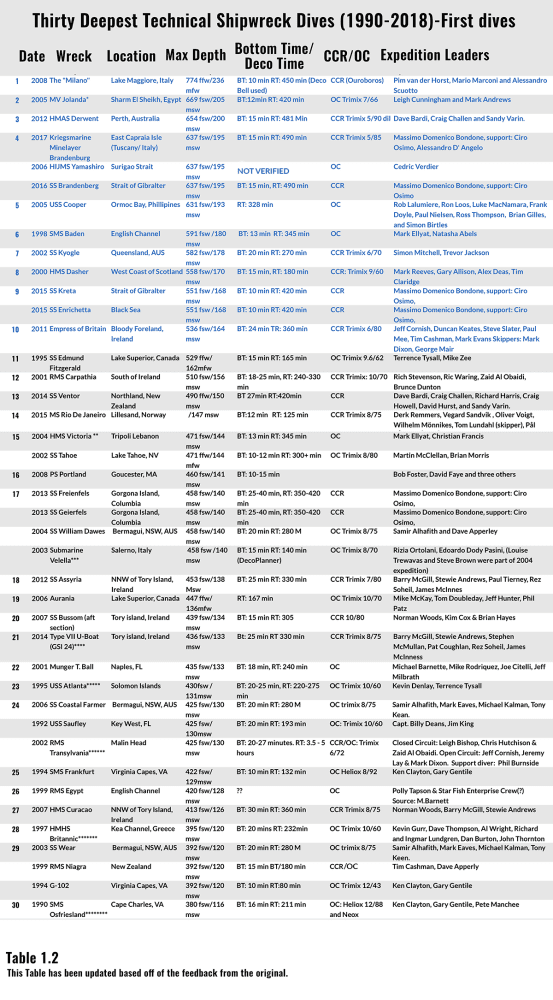

The Deepest Shipwreck Dives Today

The second table shows the 30 deepest technical shipwreck dives as of this year identifying the first tech teams to dive on the wrecks. Note that only the eight deepest shipwreck dives from the 1990s made it on the list. The deepest tech shipwreck dive, was on the Milano lying at a depth of 774 fresh water (236 mfw) in Lake Maggiore, Italy, (the equivalent of 751 fsw/176 msw), conducted by Pim van der Horst, Mario Marconi, and Alessandro Scuotto in 2008, with the help of diving pioneer Nuno Gomes who was a consultant and witnessed the dive.

August 14, 2022—Editor’s Note: Leo Fielding reports that he and his team explored the SS Mahenge located in the English Channel at a maximum depth of 121msw /395 fsw, which would make it the 27th deep tech shipwreck dive. The dive was conducted on CCR using a trimix 8/80 diluent; bottom time was 28 minutes, runtime was 238 minutes.Expedition team: Leo Fielding, Joe Colls-Burnett, Andrew Colderwood and Luke Sibley skippered by Ian Taylor on the boat Skin Deeper. The wreck was reportedly dived in 2006 by a UK team skippered by Grahame Knott on the boat Wey Chieftain III, and dived again in the 2010s by a UK team led by Jos Greenhalgh and skippered by Ian Taylor. Thank you for the update Leo Fielding!

The 30th deepest wreck dive is now the SMS Ostfriesland (380 ft/116 m), which was just slightly shallower than the average depth of the Ten Deepest Shipwrecks from 1990. The deepest wreck dive in the 1990s, that being the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, aka ‘The Fitz,” laying at 529 ffw/162 mfw, is now #11 when viewed from today. That is to say that the top ten deepest shipwreck dives were all conducted after 2000.

Note also there is one high altitude shipwreck dive on the list being the SS Tahoe at 471 feet of fresh water/144 m, the equivalent of 457 ft/140 m of seawater, which lies in Lake Tahoe at an altitude of 6224 ft/1897m. The altitude makes the SS Tahoe a no-man’s land in terms of decompression knowledge; there is almost no data to validate procedures for aggressive dives at that altitude. Only Sheck Exley and Nuno Gomes’ series of sub-500ffw/153mfw open-circuit cave dives in 1992-1996 at Boesmansgat sinkhole that lies at an altitude of 5000 ft/1500m in South Africa were possibly more extreme.

Also interesting, 9 of the 13 wreck dives in the deepest 10 today (there were multiple shipwrecks at the same depth) were conducted on rebreathers vs. four on open-circuit scuba. All but one of the 10 deepest shipwreck dives in the 90s were conducted on open circuit. All the 30 deepest dives but two, were made using trimix as a back gas or diluent, the exception was the Frankfurt and Ostfriesland first dived by Clayton and Gentile and team as noted above.

Closed-circuit technology is largely responsible for the deeper depths and longer dives we see today. The average depth of the ten deepest shipwreck dives listed in chart two is 576 ft/176m, or 178 ft/75 m deeper than the ten deepest shipwreck dives from the 1990s. Average bottom time for the deepest 10 today was 15 minutes compared to 16.7 min for the 1990s wrecks, however average run time was 316 minutes or more than five hours, compared to a little over three hours in the 1990s.

The amazingly prolific Italian diver Massimo Domenico Bondone and his team accounted for six of the dives in the 20 of the 30 deepest shipwrecks! Wow! He is followed by Irish tekkie and photographer Barry McGill, his colleague Stewie Andrews, and their various teams who were responsible for four of the deepest dives shown on the table. Aussie tekkies Dave Bardi, Craig Challen, Richard “Harry” Harris and their colleagues from the “Wet Mules,” who were prominent in the Thai cave rescue earlier this year, were responsible for three of the dives as were Ken Clayton and Gary Gentile (from the 1990s). Tysall was responsible for two dives on the list, the Fitzgerald and the Atlanta.

Have we bottomed out our depth capability as self-contained divers? If history is any judge likely not. My long-held belief is that self-contained atmospheric diving systems aka Exosuits or hard suits, such as those pioneered by commercial pioneer Phil Nuytten, founder and CEO of Nuytco Research, represent the next wave of technology that promises to extend our envelope even further. However, given the slow pace at which diving technology evolves (it’s a matter of economics), it may be a while before divers will have access to $10,000 swimmable Exosuit.

Even so, it will be interesting to see what the list of the 10 deepest tech shipwrecks dives will look like in 2029.

For the deepest cave dives see: Diving Beyond 250 Meters: The Deepest Cave Dives Today Compared to the Nineties

Editor’s Note: This post evolved based on input from our readers. Here were the two earlier versions:

Resources

How Deep is Deep? The 20 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives and How They Compare to Dives in the 1990s

Extending The Envelope Revisited: Correcting The Record of the 30 Deepest Tech Shipwreck Dives

A printed version of this article was published in the “Journal of Diving History, Third Quarter 2019, Vol 27 Number 100.

Footnotes

Table 1: 1990s

Deepest 10 (1989-1999): Average depth: 398 fsw/122 msw, Avg Bottom Time: 16.7 min Average Run Time: 192 min

*Note that Tysall & Zee’s dive on the Fitz was not a “sneak” dive. The two obtained permits to dive the wreck but they didn’t allow the divers to tie in.

** Denlay & Tysall’s first dive in 1995 was to 361 fsw/110msw on the shallow stern of the Atlanta. They returned in 1997/98 where they made their deepest dive to the bow.

** Jacque Cousteau, Albert Falco (team leader), Raymond Coll (camera), Ivan Giacoletto (lights) and Robert Pollio (photo), were the first to dive the Britannic in 1976. Their first recon dive was on air!! Subsequent dives with BT: 15 min were made with Trimix 14/54. The team deco’d in a bell. GUE launched its own expedition in 1999 which included the Lundgren brothers.

Table 2: 30th Deepest

Deepest 10 (1990-2018): Average depth: 576 fsw/1176 msw, Avg. Bottom Time: 15min, Avg. Run Time: 374 min

*The Jolanda sits vertically from 70-150 msw. According to M. Ellyat, Gregory ‘Banan’ Dominik found and dived the deep bit of the Yolanda in Sharm 3 years before Mark Andrews and Leigh Cunningham.

** According to M. Ellyat When he found the Victoria in 2004 it was almost intact in 156m. Subsequent dynamite fishing has blown the inner decking down to the seabed making it appear 144m.

***Rizia Ortolani set the then Deep Wreck Female record on this dive.

**** Scuttled in Operation Daylight, Operation Deadlight Type VII.

*****Denlay & Tysall’s first dive in 1995 was to 361 fsw/110msw on the shallow stern of the Atlanta. They returned in 1997/98 where they made their deepest dive to the bow.

****** The wreck had been dived previously in September 2000 by Richie Stevenson, Chris Hutchison and Dave Greig but only as a bounce w/ 2 min bottom time. Subsequent dives with BT: 15 min were made with Trimix 14/54. The team deco’d in a bell. Greek commercial diver Kostas Thoctarides followed Cousteau in 1995 making a solo 20-min dive, and returned in 2001 with a submersible.

********Clayton dived Neox mix (O2 and Ne) for their last dive on Ostfriesland to 340 f/104 m with 20 min BT.

Michael Menduno is InDepth’s executive editor and, an award-winning reporter and technologist who has written about diving and diving technology for 30 years. He coined the term “technical diving.” His magazine “aquaCORPS: The Journal for Technical Diving”(1990-1996), helped usher tech diving into mainstream sports diving. He also produced the first Tek, EUROTek, and ASIATek conferences, and organized Rebreather Forums 1.0 and 2.0. Michael received the OZTEKMedia Excellence Award in 2011, the EUROTek Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012 and the TEKDive USA Media Award in 2018.