Latest Features

The Case for Biochemical Decompression

How much do you fart during decompression? How about your teammates? It turns out that those may be critical questions if you’re decompressing from a hydrogen dive, or more specifically hydreliox, a mixture of oxygen, helium, and hydrogen suitable for ultra-deep dives (Wet Mules, are you listening?). Here the former chief physiologist for the US Navy’s experimental hydrogen diving program, Susan Kayar, gives us the low down on biochemical decompression and what it may someday mean for tech diving.

by Susan R. Kayar, PhD

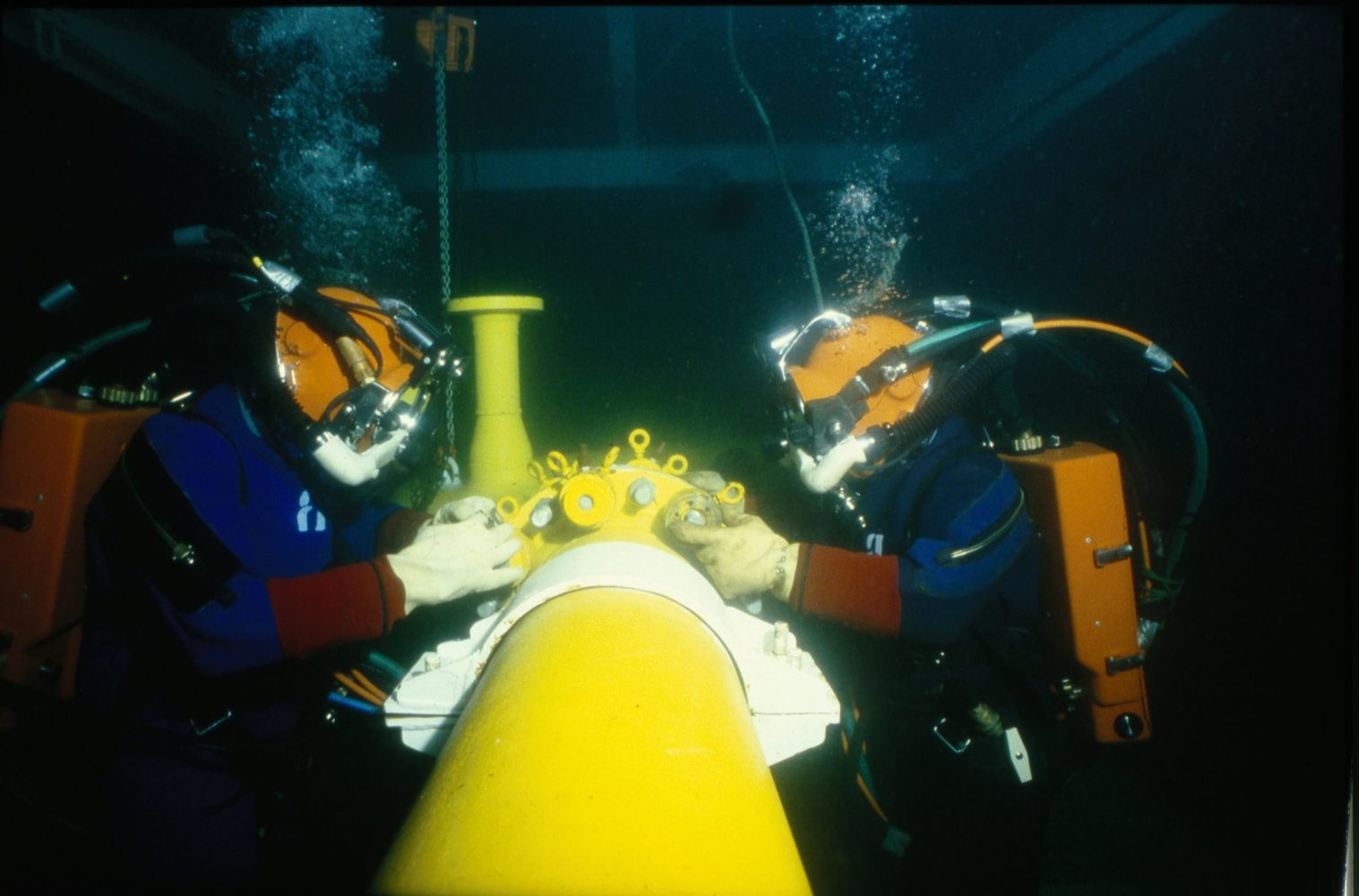

Header courtesy of A. Tocco Comex

Thirty years ago, the Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI) in Bethesda, Maryland, hired me for what at the time I thought was the coolest job I could ever be asked to do. I still think so. I was hired to be the physiologist for their experimental hydrogen diving program. Why dive with hydrogen? A recent InDepth article by Reilly Fogarty, “Playing with Fire: Hydrogen as a Diving Gas”, does an excellent job of explaining this subject. The short answer: because hydrogen is the smallest molecule.

One might think that in an era with excellent one-atmosphere hard suits, and multiple forms of submersibles and robotics, there is no need to send bare-naked divers to the sorts of depths involved in hydrogen diving, as will be described shortly. If these alternatives to divers are so great, why do we still use commercial divers at all? One needs to ask an operational person this question, rather than a scientist like me. But I think the words “logistics”, “costs”, “safety,” and “the direct human touch” would figure in the answers.

Once a diver dives deep enough to exceed safe limits with regard to nitrogen narcosis, the usual gas switch for the diluent to oxygen is helium. However, if a diver keeps on going into the range of 1000 to 2000 feet of seawater (roughly 300-600 msw), a helium-oxygen gas mixture becomes dense enough that the work of breathing becomes difficult. Divers fight to move this dense gas into and out of their lungs, making the effort to breathe a serious source of fatigue and a distraction to their assigned jobs. (See “Maintaining Your Respiratory Reserve,” by John Clarke). Hydrogen is a diatomic molecule (i.e. H2) with two protons and no neutrons, and is therefore half the molecular weight of helium, a monatomic molecule with two protons and two neutrons. Therefore replacing helium with hydrogen, eases a diver’s respiratory distress i.e. work of breathing.

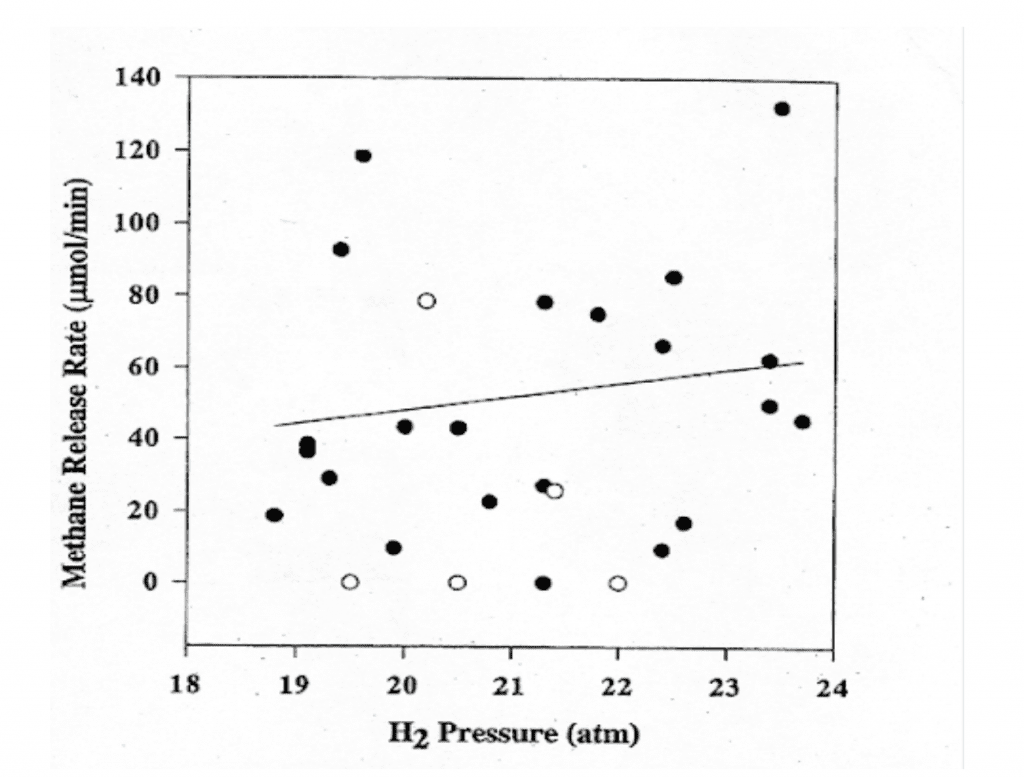

There is also a phenomenon of ultra-deep diving known as High Pressure Neurologic Syndrome, or HPNS, (also known as High Pressure Nervous Syndrome) which is evidently a function of high pressure interfering with the transmission of signals in the nervous system. Symptoms of HPNS can range from tremors to confusion to psychosis and are highly variable in depth at onset and from diver to diver. For unknown reasons, hydrogen at high pressure is narcotic and can suppress HPNS. Past a very high pressure that again varies with the diver, but generally on the order of 23 atmospheres partial pressure of hydrogen, its narcotic properties can become overwhelming and have their own psychotic effects.

There are also serious issues involving the explosivity of hydrogen in combination with oxygen, but these issues are manageable with the care one always uses in handling oxygen and other combustible and hyperbaric gases. Hydrogen and oxygen can be combined safely if the oxygen content is less than 4% of the gas mix, with dive operations usually opting for 2% oxygen as their safe upper limit. A 2% oxygen mixture is breathable if the total pressure is 10 atmospheres (roughly 90m/295 f) or more. This is normally accommodated by starting a pressurization with helium and then switching to hydrogen after 10 atm. As a final consideration, the price of helium is rising, and may make hydrogen substitution increasingly attractive. Consequently, for a variety of practical reasons, hydrogen has a potential place in ultra-deep diving beyond 10 atmospheres of pressure.

Investigating Biochemical Decompression

As the physiologist to the hydrogen diving program at NMRI, my assignments were two-fold: first, to determine if there are any dangerous biological effects that had been previously overlooked of breathing hyperbaric hydrogen, and second, to look into something that NMRI was calling “biochemical decompression,” or “biodec,” a term they had coined themselves.

The unknown dangerous biological effects portion of the research was addressed first. The short answer to that was “none”. We found no evidence that inhaled hydrogen could participate in any unwanted biochemical reactions in the body, discounting whatever reactions eventually make hydrogen narcotic. We still do not know exactly why hydrogen becomes narcotic, but it is unlikely from the physical properties of hydrogen that its narcotic effects are permanently harmful post-dive.

Then we got to the really exciting part of the hydrogen research program at NMRI: biochemical decompression. A few years before I was hired in 1990, a biochemist at NMRI, Dr. Lutz Kiesow, heard it was possible for divers to use hydrogen as a breathing gas. He knew there were many microbes that possessed a hydrogenase enzyme allowing them to consume hydrogen gas as a metabolic source equivalent to the consumption of oxygen as a metabolic source for most land organisms. End products for hydrogen metabolism can vary with the microbe, but is often methane (CH4). Hence, as a class, such microbes are called “methanogens”.

Dr. Kiesow proposed that NMRI establish a research project to isolate the hydrogenase from a methanogen, and insert it somewhere in the body of a diver to effectively create a chemical scrubber unit for hydrogen. If a diver could continuously scrub out some of the hydrogen going into solution in his body during the dive, the diver would have a reduced body burden of inert (to the diver) gas, and could subsequently decompress more rapidly with lower risk of decompression sickness (DCS).

What a cool concept! I loved it from the moment I heard it. But the real challenge was to resolve Dr. Kiesow’s “somewhere in the body” requirement into a safe, readily reachable, functionally useful body location. The director who hired me understandably warned me that divers would be opposed to receiving routine injections, or any sort of biological implant making them Bionic Men, permanently different from their former selves or from other divers. So what was left?

On my first musings with the scientific head of NMRI when I was hired, I wondered if we could perhaps encapsulate the hydrogenase enzyme, or better yet just whole methanogens, and swallow the capsules down for delivery to the large intestine as the working location for this scrubber unit. The scientific head instantly responded he had been thinking the same thing, but had not wanted to bias my thinking by saying it first. The approach met all our criteria. Taking capsules by mouth is as easy and as non-invasive a way to get things into the body as there can be. The large intestine has many microbial species living there safely and performing many jobs that we are slowly realizing are important to our health.

Trust Your Gut?

Methanogens typically are anaerobic organisms that would die quickly if exposed to oxygen, and the large intestine is the only part of the body that provides an anaerobic environment. Some species of methanogens are even a normal part of our intestinal flora, where they consume traces of hydrogen manufactured by other intestinal microbes. We were therefore confident that adding more methanogens should do no digestive harm. The amplified population of methanogens in the intestine would be likely to stay high only for as long as the divers breathed hydrogen, and return to baseline shortly after the exposure to hydrogen ended. The methane end product of this hydrogen scrubbing has a safe means of escaping from the intestine.

The methane-releasing issues were the only parts of this research that got a little weird at times. I was very carefully coached by Navy people to use lengthy euphemisms such as “the methane is released to the environment following the path of least resistance,” or “methane has an obvious means of egress from the intestine.” I was warned never to use what I have come to refer to as “the four-letter f-word” for methane release. But the euphemisms never helped. All audiences instantly understood the euphemisms as such.

Indeed, I came to consider it a sign that my audience was truly listening to me and following the science when they suddenly started squirming in their seats and trying with greater or lesser success to cover their laughter when I started explaining the fate of methane. Jokes followed. One Navy brass listener asked me if the implementation of hydrogen biochemical decompression meant a negation of the stealth intended for Navy SEALs when they used closed-system (i.e., non-bubbling) breathing rigs. The only sensible thing for me to do was laugh along with the room.

An interesting phenomenon happened as soon as people got over their initial laughter at this childishly scatological word that I did not say but that they obviously thought of themselves. They started thinking about the physiology and the gas transfer physics I was describing, and they liked it. No more laughter after that moment of enlightenment arrived. So go ahead and laugh now. “Better out than in” applies to laughter also. I got a million of ’em. I am known in some circles as the “Queen of Farts” with good reason.

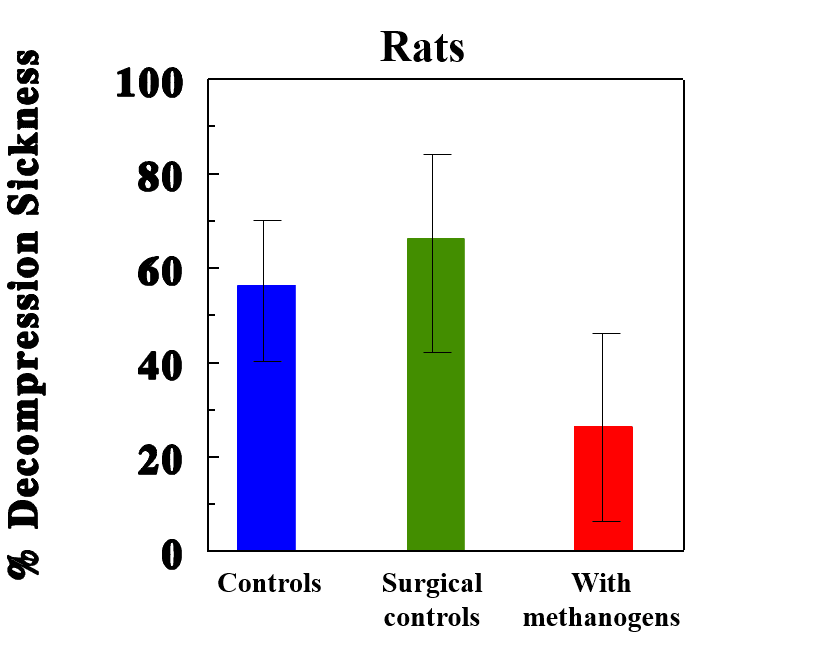

Measuring Flatulence err Farts

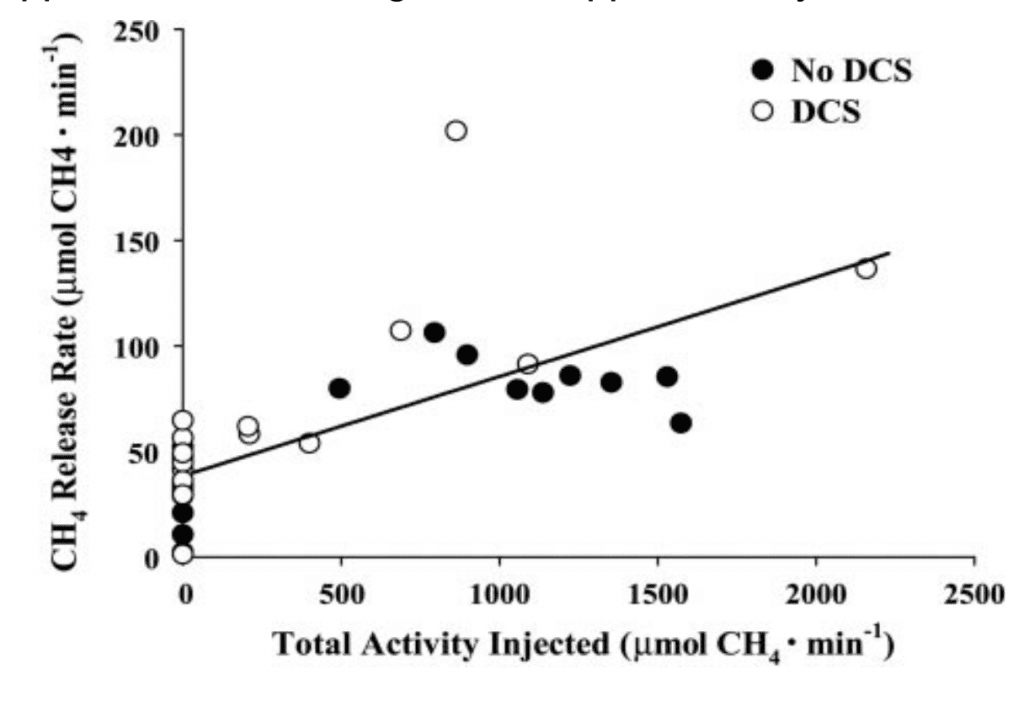

I retired from Navy civilian service years ago, so I can say whatever I wish. I measured farts. Measuring farts is funny. And measuring farts in rats and pigs is exactly how my NMRI team and I succeeded in demonstrating the feasibility of hydrogen biochemical decompression to reduce the incidence of DCS following hydrogen dives by roughly half. As far as we know, methane release rate is the only variable that can be biologically manipulated with a measurable effect on DCS incidence following any kind of dive. There is nothing humorous about reducing DCS incidence.

The methanogenic species we chose has a rather grand first name but oddly mundane last name: Methanobrevibacter smithii. It is native to the intestinal flora of many mammals, including humans and pigs, and thus does not cause digestive issues when added to the intestines. The metabolic equation for M. smithii is the following:

4H2 + CO2 = CH4 + 2H2O

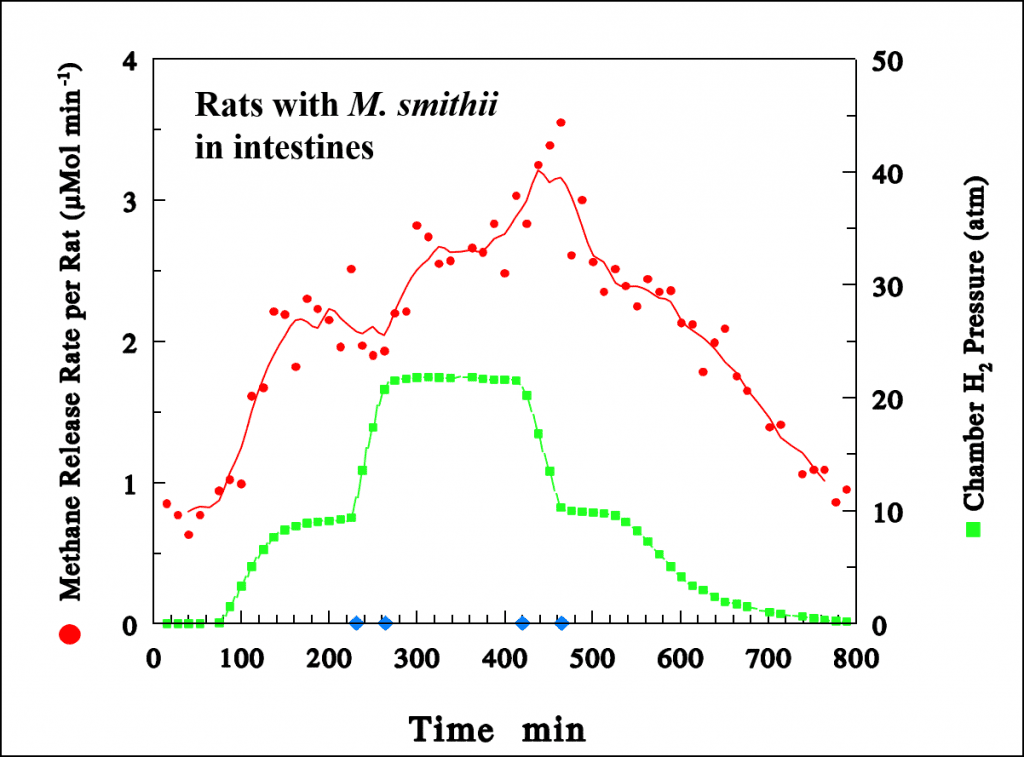

To speed things along in the lab, we surgically injected M. smithii cultures into the upper end of the large intestines of our lab animal models of divers, which were initially rats and later pigs. The animal-divers were then placed in a hyperbaric chamber which we pressurized with hydrogen and oxygen. Some hydrogen and oxygen breathed by an animal-diver dissolves in the blood for transport throughout the body. When the blood circulates through the vasculature of the intestinal wall, some hydrogen diffuses down its partial pressure gradient into the intestinal cavity, where the M. smithii are housed.

Oxygen is taken up by the cells of the intestinal wall and aerobically metabolized to carbon dioxide (CO2), some of which also diffuses into the intestinal cavity. M. smithii metabolizes the hydrogen and carbon dioxide to methane and water. The animal-diver safely absorbs the water. It is a real scientific benefit that the methane exits the body as easily as it does. Since no mammalian cell manufactures methane, we could track the metabolism of our methanogens inside our animal-divers simply by measuring the rate of release of methane from them to the surrounding environment by gas chromatography. As the hydrogen pressure in the chamber increased, we measured increasing quantities of methane in the chamber gases

When we then decompressed our animal-divers, on average, the animals with supplemental methanogens had approximately half the incidence of DCS as those without supplements. As the volume of methane they released during the dive increased, their incidence of DCS decreased.

Knowing from the metabolic equation above that four hydrogen molecules are consumed for each methane molecule manufactured, we could easily estimate the rate of hydrogen-scrubbing inside our animals. Based on the solubility of hydrogen in body tissues (which we guesstimated as being similar to water), and the time at pressure of the dive, we could estimate how much hydrogen would dissolve in an animal of a given body mass by the end of the bottom time, and what fraction of that body burden of hydrogen had been eliminated by our process. We computed that when M. smithii eliminated approximately 5% of the hydrogen dissolved in our animal-divers’ bodies, DCS incidence was reduced by 50% (Fahlman et al, 2001).

Human Biodec

Having succeeded in demonstrating hydrogen biochemical decompression in a small animal model, the rat, and a larger animal model, the pig, we are at least scientifically prepared to extend this work to human divers. A diver would make a saturation dive (commonly abbreviated to “sat”, meaning a dive sufficiently long i.e. 24 hours or more, to saturate the diver’s tissues with the breathing mixture) using a hydrogen-oxygen blend we usually call “hydrox”, or a hydrogen-helium-oxygen trimix which goes by the awkward name of “hydreliox”, depending on practicalities.

Dive operations may even opt for a quad-mix including nitrogen. The ultra-deep diving trials at Duke University found the narcotic properties of nitrogen helped to suppress HPNS, which was so problematic for their divers breathing heliox. However, the interaction is complex. Since we are still working out the exact mechanisms that make nitrogen and hydrogen narcotic under pressure, it remains to be determined if combining nitrogen and hydrogen for deep sat dives makes narcotic issues better or worse. The issue deserves testing.

Regardless of the other gases in the sat diver’s mix, if there is hydrogen, then hydrogen biochemical decompression could be considered. A couple of days before the end of the bottom time, the diver would prepare to biochemically decompress as a supplement to the physical decompression. The basic process would be identical to that for our animal models, except for a gentler way of delivering the methanogens to the diver. We would freeze-dry cultures of M. smithii and pack them into oral-delivery capsules designed to dissolve only under the conditions inside the large intestine. It would take around 24-36 hours to have a capsule arrive in the intestine, dissolve, and re-activate the methanogens. We would know that the M. smithii were on site and sufficiently active by chemically analyzing the sat chamber gases for methane output. Then we would get to watch the diver not bend as he decompressed faster than divers in other hydrogen diving operations without biochemical decompression. As I said, coolest job ever, or what?

But wait!

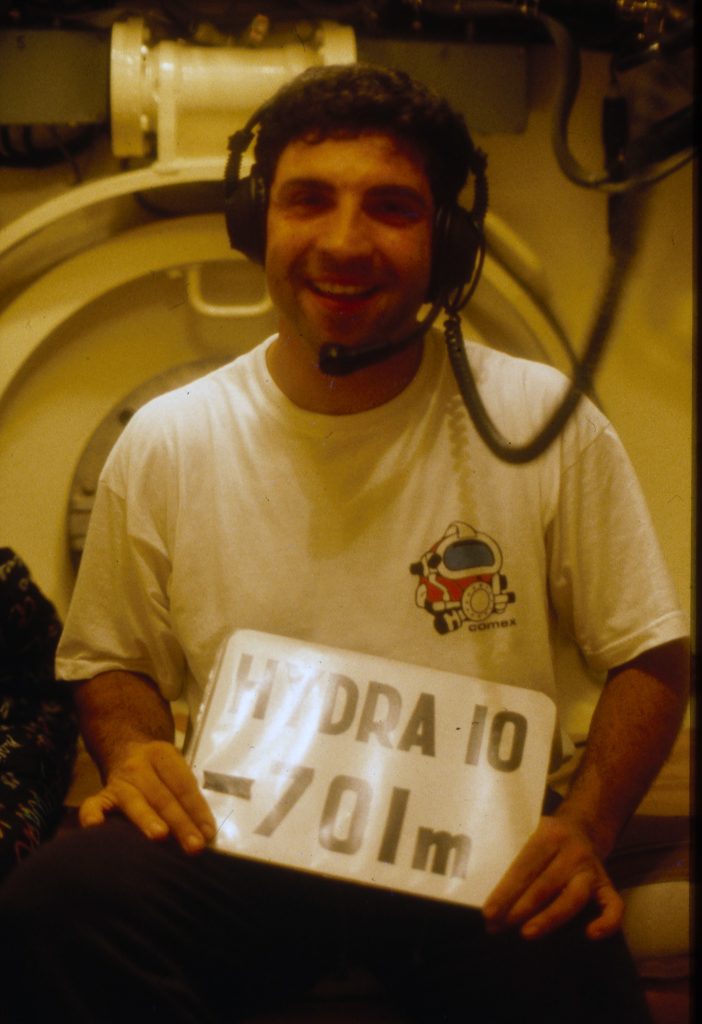

There is one more really exciting finding to report. We have evidence that even the quantity of methanogens native to the intestinal flora of a pig can provide sufficient hydrogen-scrubbing activity to reduce DCS incidence from a hydrogen dive (See Fig. 4 below). Humans and pigs are similar in many respects, including basic intestinal flora. It may well be that any human divers on a hydrogen dive, such as those at COMEX , have already benefited from hydrogen biochemical decompression without realizing it. They have only to test for methane in their chamber gases to know.

Skeptics have argued that the relatively small percentage of hydrogen scrubbing we have computed may be far too little to have any impact on DCS risk in human divers or to make a worthwhile reduction in decompression times. In addition to pointing to our DCS incidence data, we note that all divers are familiar with how important small differences in gas loads can be in DCS risk. If we dive within the time at depth limits of our chosen algorithms, we are confident to a very high level of probability that our dive will end safely. But exceeding our planned no-decompression limits by even a few minutes, and thus adding only a relatively small percentage increase in our inert gas load beyond what we think of as safe, makes our dive profile much riskier. [Ed. Note: These are computational risks not necessarily operational ones i.e. small changes in times/depths are unlikely to result in DCI] Likewise, we are all in the habit of making what we term a “safety stop” in 3-5m/10-15 ft even from a low-risk, no decompression time-requiring dive.

Sat dive operations currently using heliox and contemplating a shift to adding hydrogen will be dismayed to realize that hydrogen is considerably more potent at inducing DCS than is helium (Lillo R.S., E.C. Parker, W.C. Porter, 1997 Decompression comparison of helium and hydrogen in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 82(3) 892-901). This would mean that costs saved by substituting relatively inexpensively manufactured hydrogen (by electrolysis of water) for increasingly expensive imported helium could be overwhelmed by the costs added in significantly longer decompression time. This is where hydrogen biodec may provide its greatest advantage: in shaving down the extra time needed for safe decompression from a hydrogen dive to something closer to that of a heliox dive. Until someone takes the step of testing hydrogen biodec in human subjects, we will not know to what extent operational decompression times could be reduced.

Nitrogen Biodec?

What comes next? In an ideal scientific world, our research in animal models would be followed by equivalent studies in human divers. However, for the time being in the post-Russian Cold War Era, the US Navy has expressed no further interest in hydrogen diving and has not offered to support human studies in hydrogen biochemical decompression. To assuage my disappointment, I wrote a novel in which hydrogen biochemical decompression is used to help save the day in a submarine rescue scenario. The novel is entitled “Operation SECOND STARFISH, A Tale of Submarine Rescue, Science, and Friendship,” available as a paperback and Kindle e-book on Amazon.

But I am still dreaming bigger than that. Since hydrogen biochemical decompression works, why not shoot for something everyone in the diving world could use? Nitrogen biochemical decompression! There are nitrogen-metabolizing microbes native to our intestinal flora. But the problems of experimentally making nitrogen biochemical decompression work are staggeringly complicated. One of many is that in nitrogen metabolism, usually referred to as nitrogen fixation, the end-products are molecules such as nitrites, nitrates, and ammonia, which are not gases that would just come bubbling out for us to measure.

These fixed nitrogen compounds would stay dissolved in the fecal material and join many more such molecules already there from protein digestion. (If you think the fart jokes are bad, consider the fecal jokes. “No shit!”-Ed.) The presence of fixed nitrogen products in feces (also known as “fertilizer” under other circumstances) suppresses the nitrogen-fixing microbes from fixing even more, since the process is energetically expensive to the microbes and done only by necessity. It would take some genetic manipulation of the microbes to get them to work for us, and some form of special molecular labeling to measure how much end products they are making. I leave those problems to future scientists to solve, while I enjoy my retirement in New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, and go on dive vacations to Hawaii, Papua New Guinea, Tahiti, Fiji, and Raiatea to keep my vestigial gills damp. I may even write another novel.

Dive Deeper

Operation SECOND STARFISH, A Tale of Submarine Rescue, Science, and Friendship

References

Bennett, P.B., R. Coggin, M. McLeod, 1982. Effect of compression rate on use of trimix to ameliorate HPNS in man to 686 m (2250 ft). Undersea Biomed. Res. 9(4)335-51.

Fahlman, A., P. Tikuisis, J.F. Himm, P.K. Weathersby, and S.R. Kayar, 2001. On the likelihood of decompression sickness during H2 biochemical decompression in pigs. J. Appl. Physiol. 91:2720-2729.

Imbert, J.P., C. Gortan, X. Fructus, T. Ciesielski, and B. Gardette, 1988. Ch. 13. Hydra 8: Pre-commercial Hydrogen Diving Project. Advances in Underwater Technology, Ocean Science and Offshore Engineering, Vol. 14, pp 107-116.

Kayar, S.R., M.J. Axley, L.D. Homer, and A.L. Harabin, 1994. Hydrogen gas is not oxidized by mammalian tissues under hyperbaric conditions. Undersea Hyperbaric Med. 21(3):265-275.

Kayar, S.R. and M.J Axley, 1997. Accelerated gas removal from divers’ tissues utilizing gas metabolizing bacteria. U.S. Patent No. 5,630,410.

Lillo R.S., E.C. Parker, W.C. Porter, 1997 Decompression comparison of helium and hydrogen in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 82(3) 892-901

Kayar, S.R., T.L. Miller, M.J. Wolin, E.O. Aukhert, M.J. Axley, and L.A. Kiesow, 1998. Decompression sickness risk in rats by microbial removal of dissolved gas. Am. J. Physiol. 275 (Regulatory Integrative Comp. Physiol. 44):R677-682.

Kayar, S.R., A. Fahlman, W.C. Lin, and W.B. Whitman, 2001. Increasing activity of H2-metabolizing microbes lowers decompression sickness risk in pigs during H2 dives. J. Appl. Physiol. 91:2713-2719.

Kayar, S.R. and A. Fahlman, 2001. Decompression sickness risk reduced by native intestinal flora in pigs after H2 dives. Undersea Hyper. Med. 28(2)89-97.

Valée, N., Weiss M., Rostain JC, Risso JJ, A review of recent neurochemical data on inert gas narcosis. Undersea Hyper. Med. 38(1)49-59

Susan grew up in the St. Louis, Missouri, area. An early fascination with the films of Jacques Cousteau inspired her to become certified as a scuba diver while still in high school. Her diving in Missouri was confined to artificial lakes with sunken rowboats, lost Coke bottles, and a few carp as the thrills. She persevered in her interests in marine sciences and attended the University of Miami as a biology major, remaining at that institution all the way through to a doctorate. After graduation, it did not take long to realize she would starve if she insisted on a job in marine biology, so she moved into studying physiology in extreme environments and exercise stress. Postdoctoral research appointments sent her from Colorado to Switzerland to New Jersey. Her dream job finally materialized in an appointment with the US Navy in the Washington, DC area, where she studied decompression sickness risk in animal models of ultra-deep diving.

Susan was inducted into The Women Divers Hall of Fame in 2001 in recognition of her Navy diving research. When funding for her Navy program ended, she managed research funding efforts for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Defense Advanced Research Programs Agency (DARPA), and the Office of Naval Research (ONR). Now in retirement, she has written a diving-themed novel, “Operation SECOND STARFISH.”