Diving Safety

The Cause Of The Accident? Loss Of Situation Awareness.

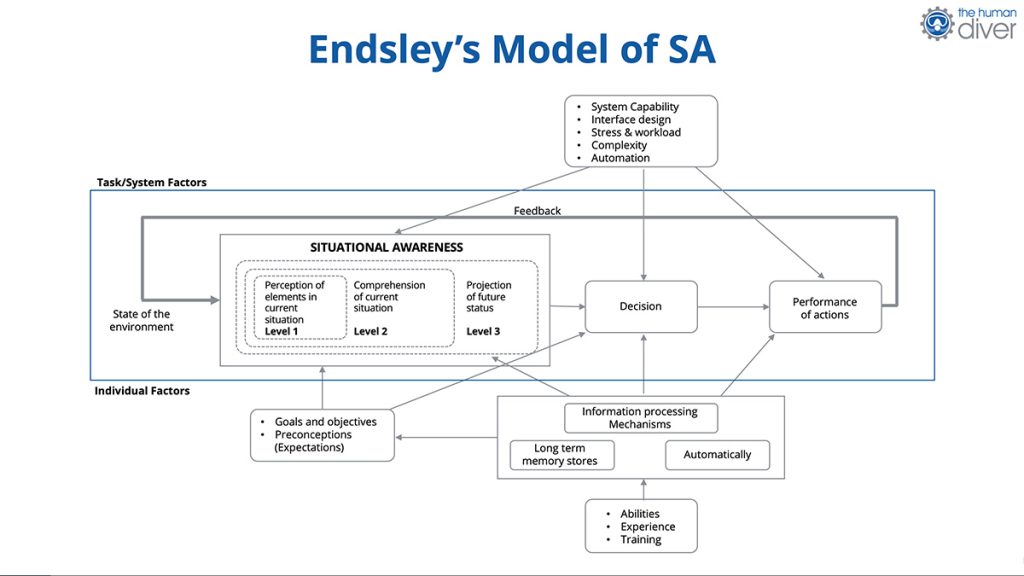

Because of our innate biases, it’s easy to blame an individual for causing an adverse event, even if that individual made good choices. In fact, according to research, in the majority of adverse events, individuals make good decisions informed by incomplete information and NOT the other way around. As Human Factors coach Gareth Lock explains, if we want to improve our outcomes, we need to understand how decisions or choices are made and how “situation awareness” fits into this. Mr. Lock proceeds to lay out his case.

Text by Gareth Lock. Images courtesy of G. Lock. Note that The Human Diver is a sponsor of InDepth.

The title of this blog comes from the numerous reports I have seen attributing the cause of an accident to be a loss of situational awareness. This could be a direct statement like the title, or it could be something like ‘they should have paid more attention to…’, ‘they didn’t notice they had drifted off the wreck/reef’, ‘they weren’t focusing on their student’s gas remaining’, ‘they hadn’t noticed the panic developing’, or one of the most prevalent, ‘it was obvious, the diver/instructor just lacked common sense’.

How many times have you heard or read these sorts of statements?

The problem is that it is easy to attribute causality to something after the event, even if it is the wrong cause! In the recent blog on The Human Diver site, a number of biases were explained that makes it easy to blame an individual for the cause when, in fact, there are always external factors present that lead those involved to make ‘good choices’ based on their experiences, skills, and knowledge, but those choices still led to a ‘bad outcome’.

Previous research has shown that the majority of adverse events are not due to ‘bad decisions’ or ‘bad choices’ with ‘good information’, rather they are ‘good decisions’ informed by incomplete information. If we want to improve the decision making of divers, we need to understand how decisions or choices are made and how situation awareness fits into this. You might notice that I have used situation awareness instead of the more common situational awareness. The reason is based on language – you can’t be aware of ‘situational’ but you can be aware of the situation.

Mental Models, Patterns and Mental Shortcuts

Our brains are really impressive. We take electrical signals from our nervous system, convert these into ‘something’ which is interpreted and matched against ‘patterns’ within our ‘memory’, and then based on memories of those experiences, we tell our bodies to execute an action, the results of which we perceive, and we go through the process again.

What I have described above is a model. It approximates something that happens, something that is far more complex than I can understand, but it is close enough to get the point across. Data comes in, it gets processed, it gets matched, a decision is made based on experiences, goals and rewards, and I then do something to create a change. The process repeats.

Models and patterns allow us to take mental shortcuts, and mental shortcuts save us energy. If we have a high-level model, we don’t need to look at the details. If we have a pattern that we recognise, we don’t have to think about the details, we just execute an action based on it. Think about the difference between the details contained within a hillwalker’s map, a road map and a SatNav. They have varying levels of detail, none of which match reality.

The following example will show how many different models and patterns are used to make decisions and ‘choices’.

Entering the Wreck

A group of three divers are swimming alongside an unfamiliar wreck and one which is rarely dived. They are excited to be there. The most experienced diver enters the wreck without checking the others are ok, and the others follow. As the passageway is relatively open, they do not lay a line. They start moving along a passageway and into some other rooms. As they progress, the visibility drops until the diver at the back cannot see anything.

The reduced visibility was caused by two main factors:

- Silt and rust particles falling down, having been lifted from the surfaces by exhaled bubbles

- Silt stirred up from the bottom—and which stayed suspended due to a lack of current— caused by poor in-water skills, i.e. finning technique, hand sculling, and buoyancy control.

The divers lose their way in the wreck. Through luck, they make their way back out through a break in the wreck they were unaware of.

This story is not that uncommon but, because no one was injured or killed, it likely doesn’t make the media, thereby possibly allowing others to learn from this event. Publicity or visibility of the event is one thing, learning from it is another.

They Lost Situation Awareness in the Wreck

We could say that they lost situation awareness in the wreck. However, that doesn’t help us learn because we don’t understand how the divers’ awareness was created or how it was being used. Normally, if such an account were to be posted online, the responses would contain lots of counterfactuals – ‘they should have…’, ‘they could have…’, ‘I would have…’ These counterfactuals are an important aspect of understanding situation awareness and how we use it, but they rarely help those involved because they didn’t have the observer’s knowledge of the outcome.

Our situation awareness is developed based on our experiences, our knowledge, our learnings, our goals, our rewards, our skills, and many other factors relating to our mental models and the pattern matching that takes place. Our situation awareness is a construct of what we think is happening and what is likely to happen. Crucially, it does not exist in reality. This is why situation awareness is hard to teach and why significant reflection is needed if we want to improve it.

The Mental Models and Patterns that were Potentially Matched on this Dive

As described above, our brains are really good at matching patterns from previous experiences, and then coming up with a ‘good enough’ solution to make a decision. The following shows a number of models or patterns present in the event described above.

- “the divers are excited…” – this reduces inhibitions and increases risk-taking behaviours. Emotions heavily influence the ‘logical’ decisions we make.

- “the most experienced diver enters the wreck…” – social conformance and authority gradient. How easy is it to say no to progressing into the wreck? What happened the last time someone said no to a decision?

- “passage is relatively open…” – previous similar experiences have ended okay, it takes time to lay line, and time is precious while diving. We become more efficient than thorough.

- “diver at the back cannot see anything.” – the lead diver’s visibility is still clear ahead because the silt and particles issues are behind them.

- “exhaled bubbles…poor in-water technique…” – none of the divers had been in a wreck like this before where silt and rust particles dropped from the ceiling. Their poor techniques hadn’t been an issue in open water where they could swim around or over the silting. They had never been given guidance on what ‘good’ can look like.

- “they lose their way…” – they have no patterns to match which allows them to work out their return route. The imagery when looking backwards in a wreck (or cave) can be different from looking forward. They laid no line to act as the constant in a pattern.

I hope you can see that much of the divers’ behaviours were based on previous experiences and a lack of similar situations. The divers didn’t have the correct matching patterns to help them make the ‘good’ decisions they needed to. Even if they did have the patterns for this specific diving situation, was there the psychological safety that allowed the team members to question going into the wreck, or signal that things were deteriorating at the back before the visibility dropped to almost zero?

As described in the recent article, ‘Challenger Safety’, team members will look to see if learner safety is present before pushing the boundaries. Learner safety is where it is okay to make a mistake; this could be a physical mistake or a social one.

Staying ‘Ahead’ of the Problem

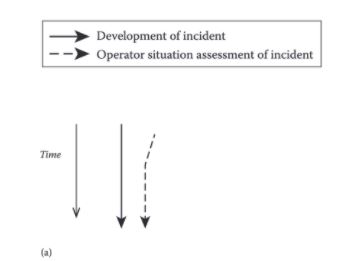

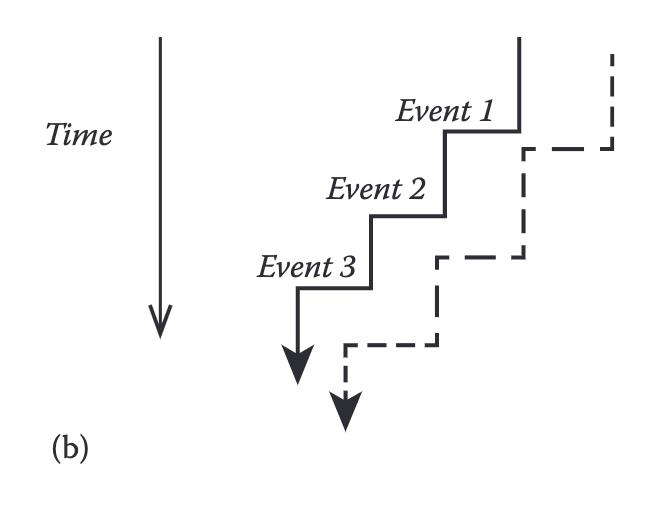

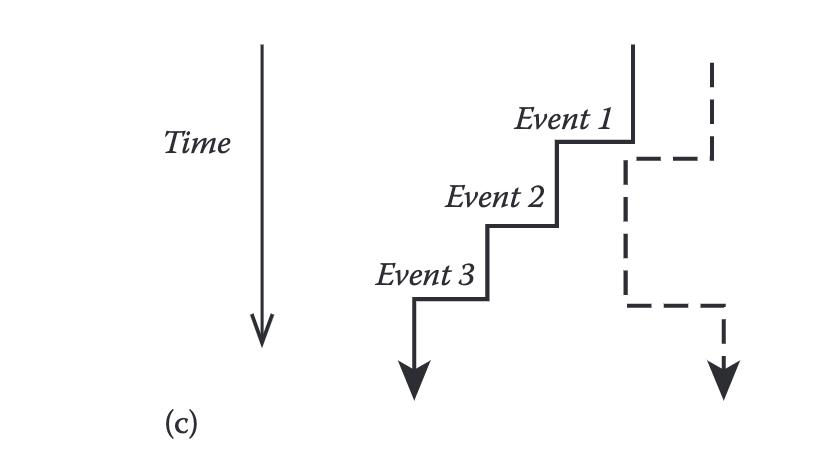

The following three models from David Woods (Chapter 3, Cognitive Systems Engineering, 2017) show how we can think about how a diver deals with an incident as it develops. Each incident is not one thing, it involves multiple activities that need to be dealt with in a timely manner. If they aren’t dealt with, there is a potential that the diver is trying to solve an old problem when the situation has moved on.

The image above shows how we used to think people dealt with problems. There was a single diagnosis to the problem, and the operator would start to align their thoughts and actions with ‘reality’ based on the feedback they were receiving.

This second image shows how a ‘perfect’ operator would track the changes as an incident developed and adapt their behaviour as a consequence. There would still be a lag, but the problems would be dealt with.

However, this image shows what happens when the operator falls behind the adaptation process, often still trying to solve an old problem, or they don’t have the models/patterns to pick up the changes then track more closely to the issue.

Consider how this would apply to the divers in the wreck penetration scenario above. Accidents and incidents happen when those involved lose the capacity to adapt to the changes occurring before a catastrophic situation occurs.

Building Situation Awareness

If situation awareness is developed internally, how do we improve it?

- Build experience. The more experience you have, the more patterns you have to subconsciously match against. This means you are more likely to end up with an intentionally good outcome rather than a lucky one.

- Dive briefs. Briefs set the scene, so we understand who is going to do what and when. What are the limits to ending the dive? We understand the potential threats and enjoyable things to see. Dive briefs also help create psychological safety, so it is easier to question something underwater.

- Tell stories. When things go well and when they go not so well, tell context-rich stories. Look at what influenced your decisions. What was going on in your mind? What communication/miscommunication took place?

- Debriefs. Debriefs are a structured way of telling a story that allows team members to make better, more-informed decisions the next time around. They help identify the steps within the events that lead to capacity being developed.

Can We Assess Situation Awareness during Dives or Diver Training?

The simple answer is no, not directly.

As described above, situation awareness is a construct held by individuals, even when operating as a team, with the team model being an aggregation of the individual’s models. The goal of The Human Diver human factors/non-technical skills programmes is to help divers create a shared mental model of what is going on now, what is going to happen, and update it as the dive (task) progresses so that the ‘best’ decisions are made.

In-water, we can only look at behaviours and outcomes, not situation awareness directly. We can observe the outcomes of the decisions and the messages being communicated which are used to share individual divers’ mental models with their teammates. This means for the instructor to be able to comprehend and then assess the ‘situation awareness’ behaviours/outcomes displayed by the team, the instructor must have a significant number of patterns (experiences) so that they can make sense of what they are perceiving. The more patterns, the more likely their perception will match what is being sensed in front of them and that their decision is ‘good’. Those patterns are context-specific too! An instructor who is very experienced in blue water with unlimited visibility will have a different set of patterns from a green water diver with limited visibility, or a recreational instructor compared to a technical instructor.

The best way to assess how effective situation awareness was on the dive is via an effective debrief which focuses on local rationality. How did it make sense for you to do what you did? What were the cues and clues that led you to make that decision? Cues and clues that would have been based on experience and knowledge. Unfortunately, a large percentage of debriefs that are undertaken in classes focus on technical skill acquisition and not building non-technical skills.

Summary

Situation awareness is a construct, held in our heads, based on our experiences, training, knowledge, context, and the goals and rewards we are working toward. It does not exist. You cannot lose situation awareness, but your attention can be pointing in the ‘wrong direction’. You are constantly building up a mental picture of what is going on around you, using the limited resources you have, adapting the plan based on the patterns you are matching, and the feedback you are getting. Therefore to improve, you must learn what is important to pay attention to and how you will notice it. It isn’t enough to say, “Pay more attention.” We should be looking for the patterns, not the outcomes.

If we want to improve our own and our teams’ situation awareness, i.e., the number of, and the quality of, the patterns we hold in our brains, we need to build experience. That takes time, and it takes structured feedback and debriefs to understand not just that X leads to Y, but why X leads to Y, and what to do when X doesn’t lead to Y. The more models and patterns we have, the better the quality of our decisions.

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 350 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and A Just Culture.