Exploration

The Life & Times of a West Coast Photogrammetrist: Could it be the Almirante Barroso?

Seattle-based instructor and photogrammetrist Kees Beemster Leverenz recounts the challenges he and his team faced trying to amass sufficient detailed footage of a mystery steamship lying 75m/250 ft beneath the Red Sea, while Murphy hammered away on the team and their equipment. What’s a photogrammetrist to do?

by Kees Beemster Leverenz

Header image and photos courtesy of K. Leverenz unless otherwise noted.

[Ed.note: Be sure to make the jump on Leverenz’s 3D model ]

About four minutes into the dive I realized I should have listened to Faisal. Nine divers in three teams, myself included, had made it to around 40 m/130 ft when the warm calm water of the Suez gulf turned into a torrent. The thick rope that connected the surface to the wreck went from vertical to nearly horizontal, and started shaking due to the powerful water flow. With a rebreather, two decompression cylinders, and a camera, I could only make headway if I turned my scooter to its maximum speed and kicked as hard as I could. Even then, progress was slow. The wreck was 37 m/120 ft away, resting in just over 75 m/250 ft of clear blue water. We had a long way to go.

Faisal Khalaf—the proprietor of Red Sea Explorers and our deep diving guide for this trip—had told us what to expect. Perhaps “warned” is a better word. However, besides being a talented diver, Faisal is an excellent storyteller with a flair for the dramatic. This had led me to believe he was being theatrical during the dive briefing in the morning, describing surging currents underwater despite placid surface conditions. He was not exaggerating.

The flow was strong, and our three dive teams resorted to a combination of negative buoyancy, scootering, kicking, and pulling ourselves hand-over-hand down the rope to get to the wreck. As I struggled against the current, another bit of the dive briefing drifted through my head: We were less than a kilometer from one of the largest shipping lanes in the world, and it would be quite dangerous to get swept off the line. Even if a large container ship could spot a diver (they can’t), and they wanted to turn, they’d be unable to. The turning radius of a modern container ship is measured in kilometers.

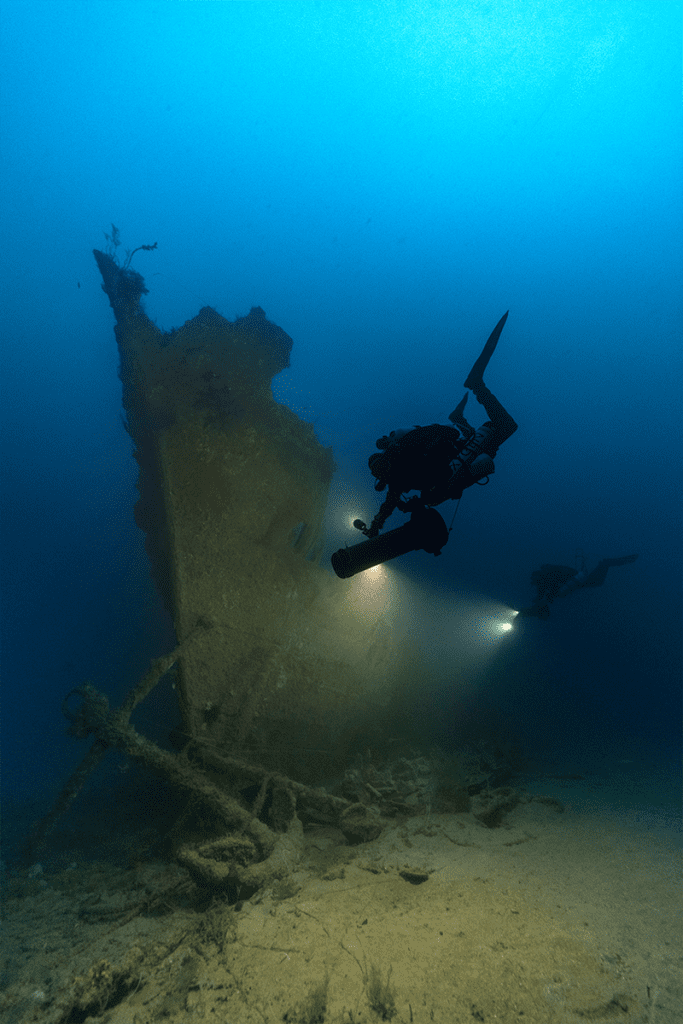

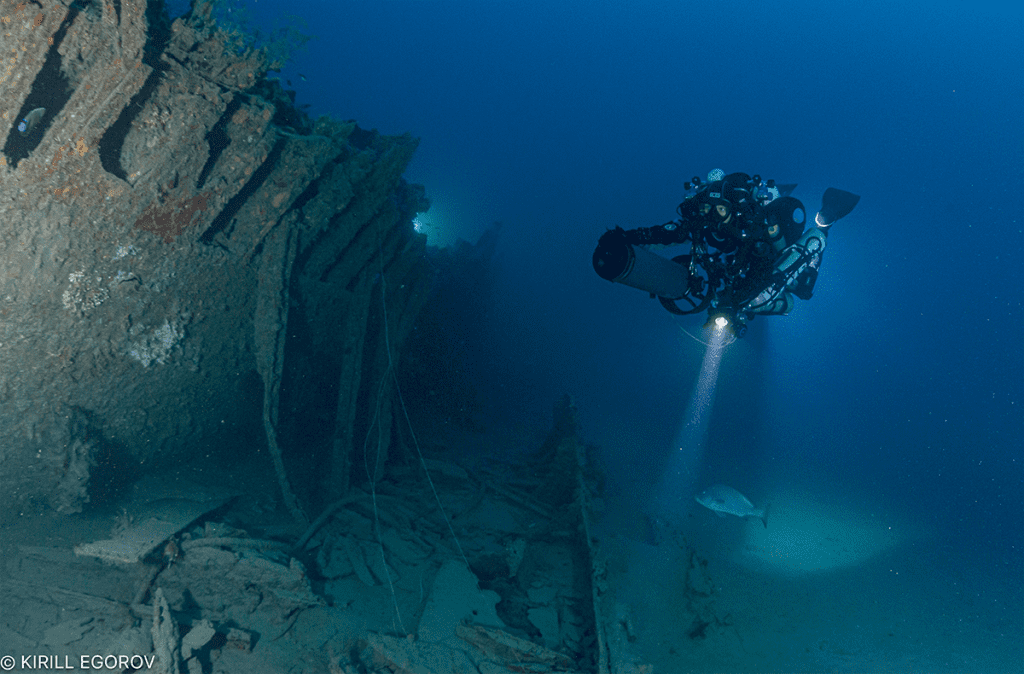

Around 60 m/200 ft, the wreck came into view for the first time: an enormous hulk, with two anchors at the bow and a large twin steam boiler at the stern. Schools of giant trevallies—each over a half meter long—darted around the wreck feeding on other marine life sheltering in the hull. On that first dive, our nine divers landed somewhat ungracefully in the protection provided by the thick steel of the wreck, which acted as a break-water to shield us from the powerful current that had challenged us on the descent. We got our bearings, breathed deep, and began our dive.

Faisal believes this wreck is the remains of the three-masted steel-hulled Brazilian steam corvette SC Almirante Barroso, sunk in 1893 when it struck the rocks of Al Zait. The SC Almirante Barroso was on a training mission for Brazilian Navy Cadets, and was attempting to circumnavigate the globe when it went down. Thankfully, the crew of the SC Almirante Barroso were rescued by the English ship Dolphin, but the wreck’s exact location remains a mystery. Although the identity of this wreck has yet to be confirmed, the location, size, and type of wreck matches closely.

Imaging A Mystery

This was my first encounter with the mystery ship, a single day expedition to an exciting new wreck in the midst of my first visit to the Red Sea. It was one of the more challenging dives I’ve ever done, somewhat surprising given the generally forgiving conditions in the Red Sea. It was a lesson in the fact that cold water and poor visibility aren’t the only thing that can make a dive difficult. Our team was one of several to visit the wreck since its discovery in early February of 2018. Previous dives had focused on taking pictures, shooting video, and searching the debris for something that would confirm its identity. However, the identity of the wreck remained an open question.

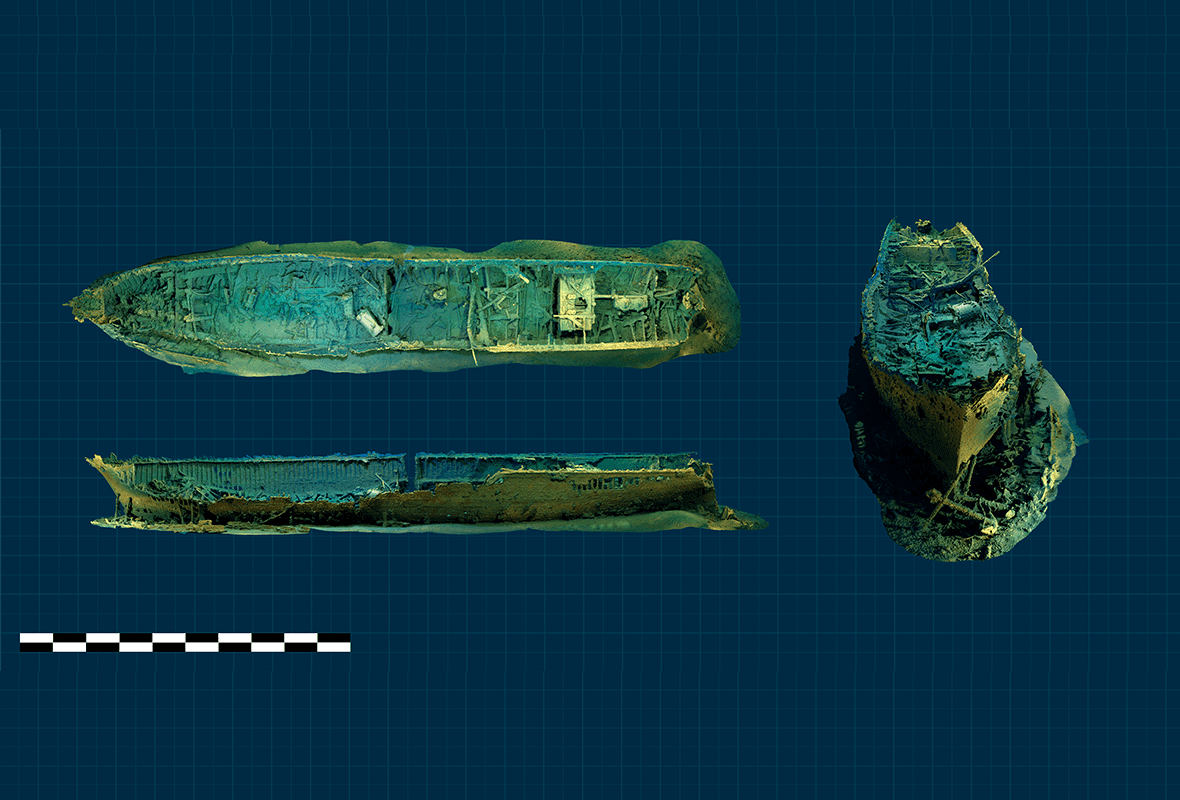

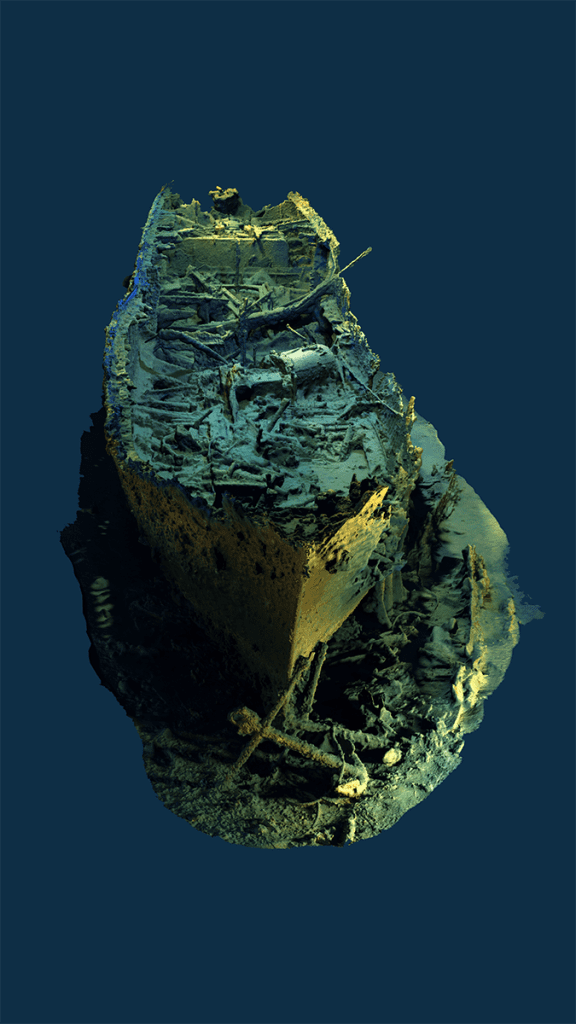

A little over eight months after my first visit, Faisal invited me to come back for the 2020 Wreck Exploration Project to try to create a 3D photogrammetry model of the wreck. The 3D model would make it easier to take measurements and to share the discovery with experts, and to perhaps allow us to unravel the mystery at the bottom of the Red Sea.

For those readers unfamiliar, the process of 3D photogrammetry relies on taking high-quality photos of every bit of a wreck, each image overlapping the last. If done correctly, sophisticated software can process the images and generate a photomosaic in three dimensions. Precise measurements can be taken from this model. However, even a small gap in the chain of images can make the whole process fail.

While we had a skilled crew and a roster of talented divers for the 2020 Wreck Exploration Project, the powerful current would make the process of taking the thousands of photos necessary exceedingly difficult, perhaps even impossible. There was only one reasonable way to conquer the currents while simultaneously taking photos, and that was to mount my camera on a scooter and take pictures on the go. This wasn’t something I’d done before.

In preparation for the challenge, I consulted two friends on their equipment preferences and bought the scooter camera mount they both recommended. I had it shipped from Italy, and it was set to arrive a week prior to my departure for Egypt. I thought a week would be more than enough time to test the scooter mount. Of course, I was wrong.

When the scooter camera mount arrived, I was shocked to discover that it didn’t work with my camera’s underwater housing. The mount used metric M6 screws to secure a camera, not the imperial ¼-20 screws my housing used. An adapter plate was available, but even if I ordered it, it would never arrive in time. Thankfully I was able to call in a favor from my friend Koos DuPreez, and we spent a day at his workshop machining an adapter from scratch. Another friend, Fritz Star, was able to give me some syntactic foam to make the scooter mount neutrally buoyant. Thanks to their generous help, my gear was ready to go for the project with a whole 24 hours remaining before my flight took off!

Hail Hail The Gang’s All here

The next morning, I started the three hops necessary to get to Egypt. First from Seattle to Washington DC, then from Washington DC to Zurich, and finally from Zurich to Hurghada. I was met at the airport by a smiling man holding a sign with my name on it. He was one of the Red Sea Explorer’s staff, sent to help shuttle me through airport security and ferry me to the MV Nouran, which would be our base of operations for the week. Considering the wide array of electronics, photo gear, and dive equipment I was traveling with, as well as the challenges of navigating airport security in a foreign country, his help was most welcome. We made it through the airport, and after a short ride through town, I arrived at the dock—exhausted but eager to see if we could make it happen.

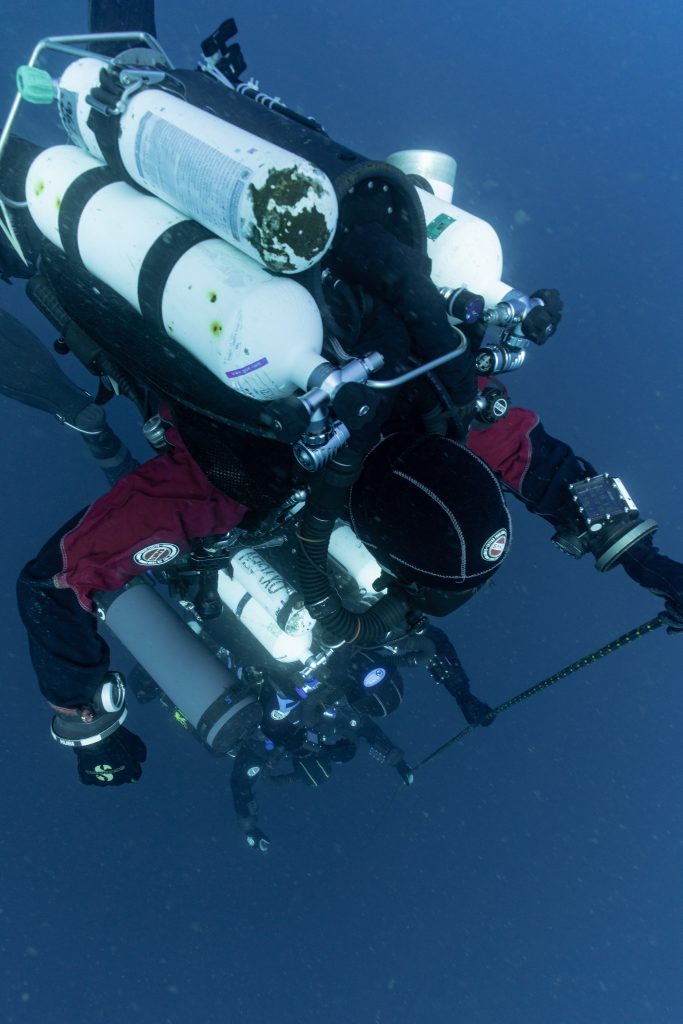

The team for this trip was originally eight strong, a small complement for the MV Nouran which could fit 24 if all her berths were filled. On arrival, I discovered that three of our divers had to drop out due to last minute complications. That shrunk our already small dive team even further. At the time of departure, the team consisted of only five divers able to safely dive the wreck: Faisal Khalaf, Kirill Egorov, Dorota Czerny, Marcus Newbold, and myself. Bernard Djermakian and Olga rounded out the team as the ship’s dive guides. While they weren’t trained to dive deep enough to reach the mystery wreck, they are both experienced divers who could act as in-water support if needed. A most welcome addition.

With such a small team and such a large boat to dive from, I immediately spread out my camera equipment on one of the MV Nouran’s four dining tables, to take stock of which pieces of dive gear survived three country’s worth of baggage handlers. I’d brought three video lights to use during the photogrammetry project. Even though I can only use two lights at a time, experience has taught me that having a spare is a good idea. Many of my diving instructors have taught me the same lesson. It was a good tip, as my quick check revealed quickly one of my three lights had broken in transit. A small but essential O-ring was protruding in a way that wouldn’t be repairable until I returned to the United States. I sent the manufacturer a message, and they confirmed what I already believed to be true: the light shouldn’t be taken in the water. I was down to the bare minimum: two lights.

The next morning, the Nouran departed with the team in high spirits and with high hopes. We wanted to waste as little time as possible, so we planned our first and second diving days to be on the mystery steamship. If all went to plan, we’d have the opportunity to dive the wreck four, maybe five times.

In addition to the mystery steamship, Faisal had secured two more leads for the Wreck Exploration Project. First, he wanted to explore a newly discovered wreck laying in 30 m/100 ft of water near an oil field. It had been scanned by a well-equipped survey ship in the area, and the wreck was definitely interesting but had never been explored. Second, he wanted to explore a pit at 95 m/310 ft near the wreck of the SS Rosalie Moller. The pit was said to contain the bow of an unknown wreck, but the only divers that had been there weren’t able to confirm anything. Of course, the team was excited by the prospects, so these two targets were added to the itinerary.

Managing Mister Murphy

On the morning of February 27, 2020, Marcus and I jumped in the water with our rebreathers, deco bottles, scooters, and my camera for our first dive of the project. Conditions were good, and currents were calm at the surface. However, we both knew the docile surface conditions betrayed nothing about the powerful flow below us. Several enormous cargo ships coasted by, carrying goods to and from Europe and Asia via the Suez Canal.

We made the short surface swim to the downline, and I decided to do a quick check of my gear before we descended, knowing that we’d incur a decompression obligation in the fight to get to the wreck itself. I examined my camera first: it was fine. My right-hand side video light also worked, and after flipping it on, it was bright even in the bright light of the midday sun. I moved to examine my left-hand side video light, and was immediately disappointed. I turned it on and I was met with several quick flashes—the death throes of the LED contained in the light—then nothing. I looked at the front of the device and discovered that its dome port was half full of salt water. It had flooded in the time it took to swim to the downline.

I shouted to Marcus about the problem and we immediately turned tail to get back to the Nouran to try to salvage our first dive of the trip. We were able to jury-rig a working light out of the corpse of the light that broke in the water and the remains of the one that broke in transit. We were back in business, in the water shortly, and on the wreck in record time.

Once we reached the bottom, I breathed a sigh of relief. After the logistical challenges and the three back-to-back flights, after all the planning and the broken lights, after the custom machining and the calling in of favors, we were here and ready to go. Blue light filtered through the deep water. Visibility was excellent. Hundreds of yellow fish were schooling around the wreck. It was time to get to work.

Marcus and I made several circuits of the wreck, doing our best to get the images we’d need for the photogrammetry model. I started the process with a circuit around the base of the wreck, making sure to capture the two anchors that lay beautifully under the bow. I then moved on to capturing the ground around the wreck, and finally I made several passes over the top of the mystery steamship, to capture the steam boilers, stove, and other debris that lay inside. The scooter-mounted camera worked beautifully, and we managed to achieve good coverage in under an hour. With our primary job complete (at least for now), we made our way back to the upline to start paying our tedious penalty for deep wreck exploration: decompression. We surfaced 202 minutes after we descended, excited to see the results of the day’s work.

In the afternoon, over lunch, I started a test run of Agisoft Metashape (the software used to create photogrammetry models). The test run was complete by dinnertime. The 3D model was more complete than I’d hoped, but less complete than I would have liked. With powerful currents running perpendicular to the wreck, staying in position was much easier on the sides of the wreck where the current was tempered by the structure of the ship itself. At the bow and stern, the weaker currents along the side of the wreck became an unobstructed flow. The sudden change in water speed makes it difficult to get the chain of images necessary for a 3D model. Despite my best efforts, the challenging conditions meant I wasn’t able to get the images I needed. The model had broken at the bow. We’d need to add more images in a subsequent dive.

Dogged Determination

The next day, the weather cooperated, and we had an opportunity to return to the wreck. Kirill and Dorota descended first, with Marcus and me following a few minutes behind. We added the pictures I believed were necessary to complete the model (and a few hundred extras, just to be sure), and then took to exploring the interior of the wreck, taking some fun pictures along the way. Sadly, we weren’t able to find anything that positively identified the wreck. We made our way back to the upline, pulled the anchor from where it’d lodged in the hull of the wreck and made the long ascent to the surface for the second time in two days.

The test processing of the model after day two showed that we’d almost certainly achieved our goal ahead of schedule. I didn’t have the computer hardware aboard necessary to complete the model, so final processing would have to wait until I returned to Seattle.

We shifted gears to explore our secondary target: the shipwreck in the oilfield. After documenting this new target, we believe it to be the wreck of an oil tender called the “Texaco Cristobal.” We also explored the pit near the SS Rosalie Moller, which was just as deep as we’d been told but far less interesting. We dubbed it the “pit of despair,” and I won’t be going back. I doubt anyone will. Although not without challenges, we’d had an extremely productive first four days of the project.

We were fortunate that the early days of the project were fruitful, as the remaining days of the project were fraught with issues. Dorota caught a bad cold, and was unable to dive for the remainder of the trip. This whittled our small dive team down to just four divers. Then (thanks to a scheduling mishap) Kirill had to depart early. He packed up and loaded his gear on a small sailboat, which took him back to port and to the Hurghada airport for his trip back home.

Our dive team was down to just three: Faisal, Marcus, and me. Fortunately, Irene Homberger was leading a trip on the Nouran’s sister-ship the Tala and was able to supplement our tiny team for a dive or two, before hopping back onto the Tala. Still, the final dives of the trip were funny: three divers diving from a ship built to comfortably accommodate 24 divers, 10 crew, and two dive guides.

We had two final dives on the mystery steamship to try to make a positive identification. Powerful winds kicked up on the second to last day, big enough to wash across the deck of the Nouran. Faisal, Marcus, and I geared up and got ready. The Nouran made several passes over the wreck, but we collectively made the decision to skip the dive. The conditions simply weren’t safe, despite the fact that the team was eager and enthusiastic to try to identify it. We dove another nearby wreck, the Ulysses, instead and were lucky enough to have a delightful encounter with an eagle ray during our dive.

Our final day of diving on the mystery steamship was safe, but uneventful. No artifacts were discovered, no markings were found, and the ship remains unidentified. The data we collected was enough to complete the 3D model. We’ve distributed the 3D model to the usual suspects: experts, researchers, and other interested individuals, but to no avail. While we still hope and believe the mystery steamship is the SC Almirante Barroso, its identity remains unknown.

We’ll just have to go back.

Dive Deeper

Here is Leverenz’s 3D model of the mystery steamship.

GUE offers a course in photogrammetry: GUE Photogrammetry.

Kees Beemster Leverenz is an enthusiastic diver and GUE instructor from Seattle, Washington, who enjoys getting in the water as often as possible. He has been deeply involved with GUE Seattle since it was founded in 2011. Currently, Kees is contributing to both local and global photogrammetry projects, as well as assisting with cave and wreck exploration projects whenever possible.