Latest Features

The New Clinical Discipline: Diving Psychology

There’s a growing awareness that like ear barotrauma or DCI, divers can also be subject to mental and emotional traumas—whether it’s overcoming a newbie’s fear of mask clearing, or coping with the aftermath of a CO2 hit that nearly cost a wreck diver her life. Welcome to the emerging new discipline of “Diving Psychology!” Clinical psychologist and scuba instructor Laura Walton ventures a diagnosis of what’s going on.

by Laura Walton

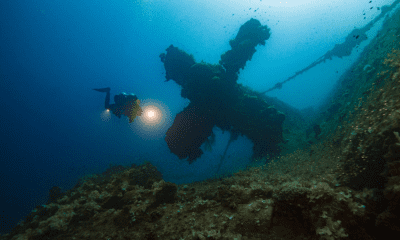

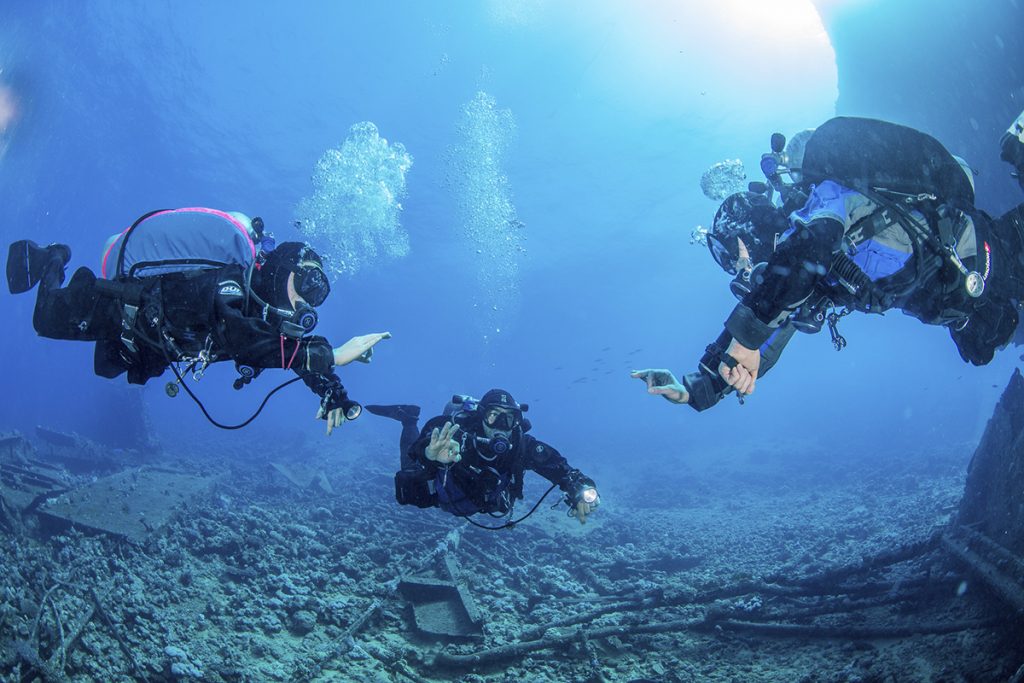

Header photo by SJ Alice Bennett.

“It can be optimistically stated that world literature provides an increasing number of reports connected with the mental functioning of divers and, to a certain extent, the new psychological discipline—diving psychology—has become more established.” Dorota Niewiedział et al, Psychological Aspects of Diving in Selected Theoretical and Research Perspectives

“I feel like someone handed me gold!” This was one of the first reactions I got when I began to provide psychological support to scuba divers a couple of years ago. The comment was from a professional diver, who was experiencing some specific anxieties while diving, and who expressed relief upon finding someone who understood what they had been struggling with for a long time. It has been a continuing theme among my clients.

Commonly, the divers I see have gotten entangled in an increasingly knotty issue, and all their efforts to escape are only making things worse. On top of that, they have often been unwilling or unable to talk to fellow divers about the issue, and when they do, the answers are not always helpful.

If you were a runner, and your foot was injured, would you continue to run on it? A high proportion of the people I work with have kept limping on, sometimes for hundreds of dives. When we have physical injuries, these cause pain and send clear signals that we need to do something about the issue. But with psychological issues, we do not always respond to the signs, and there is often more of a pressure to keep going. This is especially the case for professional or technical divers: How do you tell your boss or your buddies that you feel like you are going to lose control underwater? People understandably fear losing their jobs or being rejected from their group of divers.

In some cases, taking a break is appropriate. But a lot of the people I speak to are highly controlled in their behaviour: It is not always about panic. Sometimes divers are just feeling very worn out by irritating, repetitive mental blocks or unwanted reactions. In fact, most of the people I have worked with are highly safety-conscious divers who find ways to mitigate risks. Unfortunately, this ability to keep going often is causing more issues. The classic reason for this is that fighting with stress or anxiety creates ever-increasing tension. By finding inventive ways to fight, suppress, or otherwise hide these issues, the diver unwittingly entrenches them.

The Need For A Diving Doc

Numbers are small, but there does seem to be a clear need for psychological support for divers, especially regarding anxiety and post-trauma reactions following distressing dives. What is wrong with a non-diving psychologist? Well, for a start, most non-divers know almost nothing about the physics and physiology of diving. Few psychologists would be able to tell you what a recompression chamber is and hardly any have an awareness of the medical treatment of decompression illness and arterial gas embolism/cerebral arterial gas embolism (AGE/CAGE).

If you were unlucky enough to have gone through a diving accident, then a non-diving psychologist would have little concept of what the treatment had entailed. Even when the diver seeking help has not been involved in an actual incident, their concept of what the issues are is limited. In most cases, the diver would need to spend time explaining why their fear of losing control and making a fast ascent is a significant risk, even for a recreational diver. Much of the session could be taken up with the diver providing definitions for words like “drop-off”, “off-gas” and “decompression stop.”

The time and effort required by the diver to bridge the gap would be significant. This vocabulary issue drains resources, but that’s not the only problem. The words we use generate shared meaning and connection; it’s hard to connect with someone who cannot see or feel what you are trying to explain to them. Diving has its own language, and speaking that language is a necessary part of working with our unique community.

There are also clear signs that direct experience of the underwater environment is clinically important. For example, when divers are addressing anxiety or apprehension, part of the work would often be to set appropriate dives to reduce psychological avoidance and increase confidence. A non-diving psychologist is limited in perspective on (1) the actual risk of the activities being set and (2) ensuring the tasks are pitched at the right level of challenge to help the diver overcome the issue safely. In fact, many of my psychology colleagues react with fear or awe at the thought of scuba diving, so their comprehension of risk is unhelpfully skewed. Furthermore, perception and acceptance of risks varies greatly in divers; a recreational holiday diving enthusiast and an elite technical diver have obvious differences when you live in the diving world.

What sort of help may divers benefit from?

Diving psychology can help and support divers in their efforts to address a range of behavioral concerns that are problematic in their diving. A recent review highlighted the need for anxiety and post-trauma treatment—which could potentially play a role in assessing a diver’s fitness to dive when experiencing psychological issues—and interventions to support a safe return to diving. There are evidence-based psychological approaches to help people who experience difficulties following a distressing or traumatic incident. A diving psychologist could adapt these approaches for diving contexts, since they would have an understanding of the nature of underwater emergencies such as running out-of-gas, entrapment/entanglement, being left at sea, unplanned/rapid ascent, and being injured in or witnessing a serious accident: essentially, the issues we see listed in accident and incident reports.

Fortunately, these incidents are rare. More commonly, divers have developed specific fears and phobias, or problematic recurrent anxiety that is a frustrating feature of their dives. In addition, sometimes issues that divers are struggling with underwater turn out to be a compartmentalized presentation of a wider concern, such as burnout, depression, or other forms of stress. It’s not unusual for someone to seek help with an issue that is showing up under the surface only to find that it links to the rest of their life.

It’s not unusual for someone to seek help with an issue that is showing up under the surface only to find that it links to the rest of their life.

Divers frequently note how important it is that when consulting medical doctors, we seek out ones who understand diving, because if they don’t, their advice can be incorrect or misleading. It is the same in clinical psychology, and there is an apparent need to support divers when needed. Diving Psychology is emerging as a niche specialty, one that can help divers understand and cope their concerns, return safely to the water, and get more out of their diving.

Special thanks to SJ Alice Bennett for the dive therapy pics! You can find more of her work here.

References

- *Dorota Niewiedział et al., (2018). Psychological Aspects of Diving in Selected Theoretical and Research Perspectives. Polish Hyperbaric Research 62(1):43-54

- Walton, L. (2018). The panic triangle: onset of panic in scuba divers. Undersea and hyperbaric medicine, 45(5), 505-509.

Dive Deeper:

- SCUBAPSYCHE: Dive Beneath The Surface

- Fixing Problems Underwater: Laura Walton takes psychology underwater.

- PADI Blog: Laura Walton Posts

Laura Walton is a clinical psychologist and scuba diving instructor bringing together psychology and scuba diving to help people with their diving. She provides specialist psychological services for scuba divers and accessible courses. Laura has been guiding and teaching scuba diving in the UK since 2012, and is currently a PADI IDC Staff Instructor at The Fifth Point Diving Centre, Blyth, UK.