Community

The Price of Helium is Up in the Air

With helium prices on the rise, and limited or no availability in some regions, we decided to conduct a survey of global GUE instructors and dive centers to get a reading on their pain thresholds. We feel your pain—especially you OC divers! InDEPTH editor Ashley Stewart then reached out to the helium industry’s go-to-guy Phil Kornbluth for a prognosis. Here’s what we found out.

By Ashley Stewart. Header image by SJ Alice Bennett.

Helium is one of the most abundant elements in the universe, but here on Earth, it’s the only element considered a nonrenewable resource. The colorless, odorless, and tasteless inert gas is generated deep underground through the natural radioactive decay of elements such as uranium and thorium in a process that takes many millennia. Once it reaches the Earth’s surface, helium is quickly released into the atmosphere—where it’s deemed too expensive to recover—and rises until it ultimately escapes into outer space.

Luckily for divers who rely on the non-narcotic and lightweight gas for deep diving (not to mention anyone who needs an MRI scan or who uses virtually any electronic device), some helium mixes with natural gas underground and can be recovered through drilling and refinement.

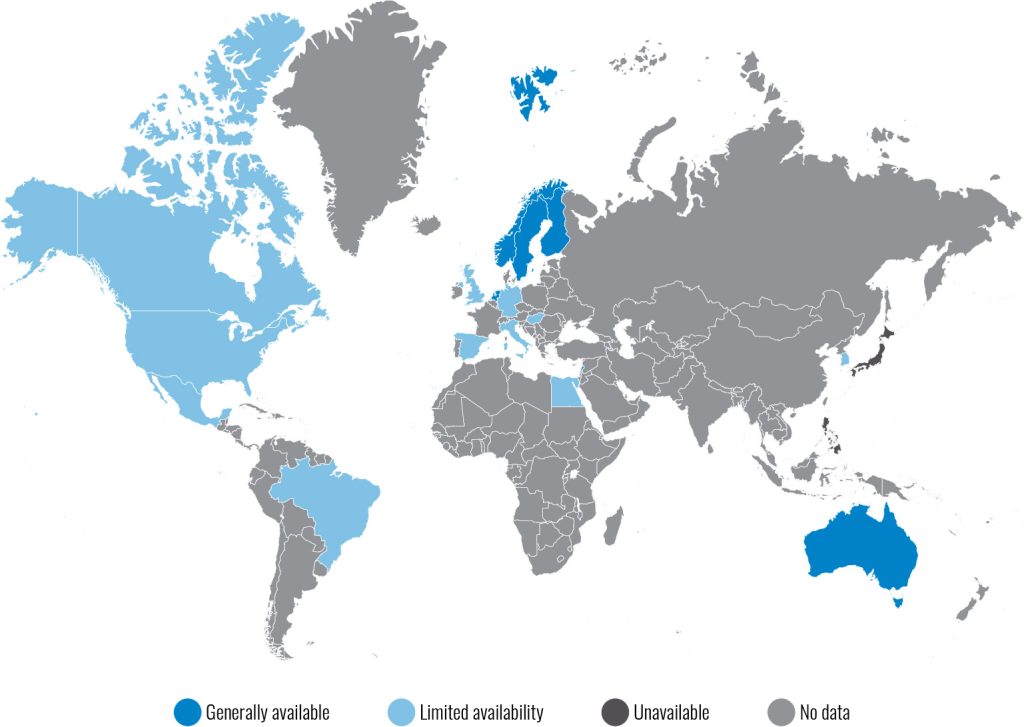

Yet the world’s helium supply depends primarily on just 15 liquid helium production facilities around the globe, making the industry uniquely prone to supply chain disruptions, which this year caused the industry’s fourth prolonged shortage since 2006. The shortage has caused many technical dive shops around the world to raise prices, limit fills, or stop selling trimix altogether, according to an InDEPTH survey of GUE instructors and affiliated dive centers.

Longtime helium industry consultant Phil Kornbluth, however, expects the shortage will begin to ease gradually now through the end of the year, and for supply to increase significantly in the future.

While a majority of the world’s helium is produced in just a few countries, a new gas processing plant in Siberia is expected to produce as much as 60 million cubic meters of helium per year, about as much as the US—the world’s largest helium producer—was able to produce in 2020. The Siberian plant ran for three weeks in September, but experienced major disruptions over the past year, including a fire in October and an explosion in January, that delayed its planned opening until at least 2023.

Meanwhile, according to Kornbluth, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management in Texas closed down from mid-January to early June due to safety, staff, and equipment issues, wiping out at least 10% of the market supply. The plant reopened in June and is back to normal production as of July 10. The supply of helium was further reduced as two of Qatar’s three plants closed down for planned maintenance, a fire paused production at a plant in Kansas, and the war in Ukraine reduced production of one Algerian plant.

With the exception of the plant in Siberia, Kornbluth said virtually all of the recent disruptions to the helium supply chain have been resolved and should yield some relief. And the future looks promising. Once the Siberian plant is online, it’s expected to eventually boost the world’s helium supply by one-third. While sanctions against Russia could prevent some buyers from purchasing the country’s helium, Kornbluth expects there will be plenty of demand from countries that as of now are not participating, like China, Korea, Taiwan, and India, though there could be delays if those countries have to purchase the expensive, specialized cryogenic containers required to transport bulk liquid helium. “Sanctions are unlikely to keep the helium out of the market,” Kornbluth said.

Meanwhile, there are at least 30 startup companies exploring for helium, and there are other projects in the pipeline including in the U.S., Canada, Qatar, Tanzania, and South Africa. “Yes, we’re in a shortage and, yes, it’s been pretty bad, but it should start improving,” Kornbluth told InDEPTH. “The world is not running out of helium anytime soon.”

THE SURVEY:

To find out how the helium shortage is affecting divers, InDEPTH surveyed Global Underwater Explorers’ (GUE) instructors and dive centers and received 40 responses from around the world.

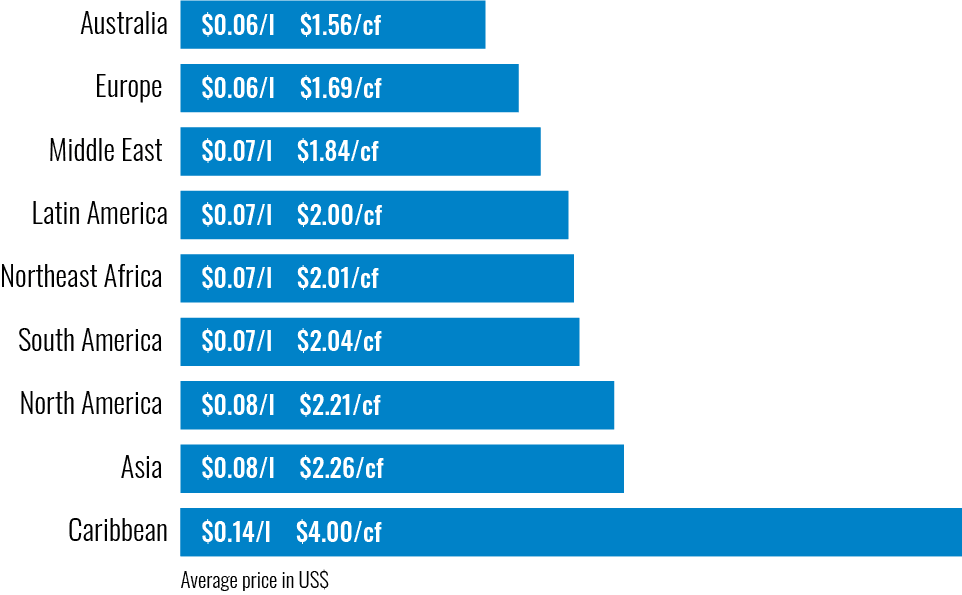

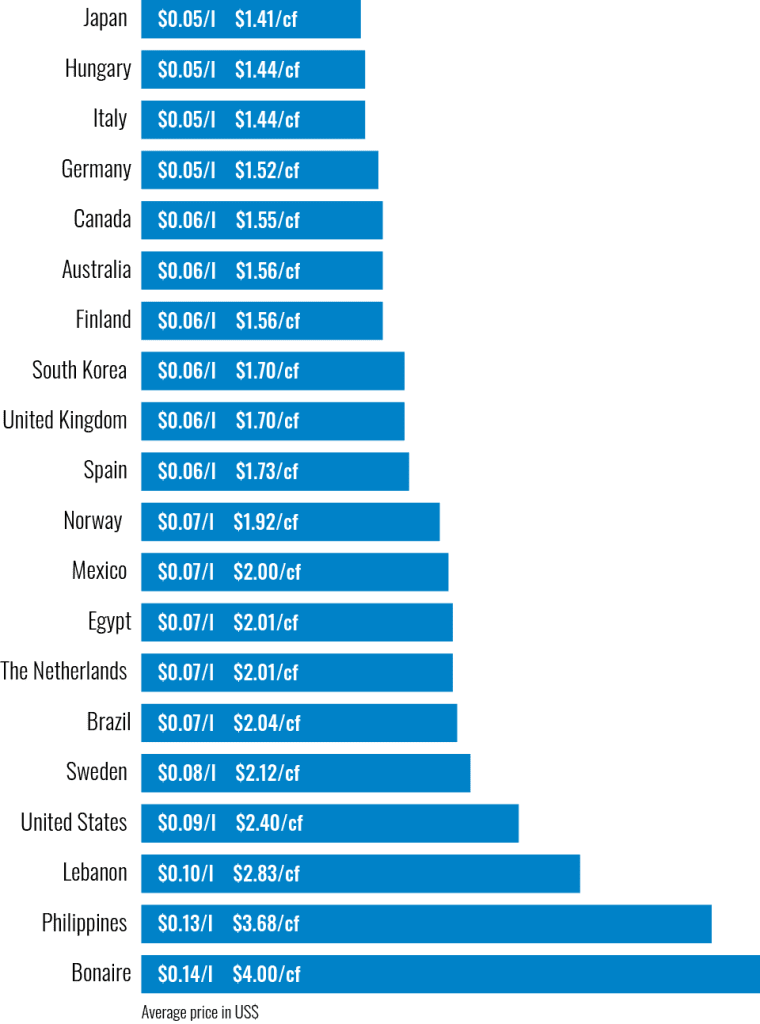

The survey’s highest reported helium price was in Bonaire—a Dutch island in the Caribbean that imports its helium from the Netherlands—where helium costs as much as US$0.14 Liter(L)/$4.00 cubic foot (cf) and is expected to rise. At that price, a set of trimix 18/45 (18% O2, 45% He) in double HP100s (similar to D12s) would cost around $360.00 and trimix 15/55 would cost $440.00.

“We have enough to support both open circuit and CCR, but in the near future, if the situation remains, we may be forced to supply only CCR divers,” Bonaire-based GUE instructor German “Mr. G.” Arango told InDEPTH. “We have enough for 2022, but 2023 is hard to predict.”

Not far behind Bonaire was the Philippines, where helium costs around US$0.13 L/$3.68 cf—if you can even get it. Based on the responses to our survey, Asia is experiencing the greatest shortages. Supply is unavailable in some parts of the Philippines, limited in South Korea, and unavailable for diving purposes in Japan as suppliers are prioritizing helium in the country for medical uses, according to four instructors from the region. In Australia, it’s relatively easy to obtain.

Four US-based instructors reported that helium prices are increasing significantly and supply is decreasing. Helium remains “very limited” in Florida and prices in Seattle increased to $2.50 from $1.50 per cubic foot ($0.09 L from about $0.05 L) in the past six months, and there was a period when the region couldn’t get helium as suppliers were prioritizing medical uses. In Los Angeles, prices have reached as high as $2.80 cf (nearly $0.10 L) and one instructor reported helium is only available for hospitals and medical purposes, even for long-term gas company clients who are grandfathered in. Another Los Angeles-based instructor said direct purchases of helium had been limited to one T bottle per month, down from three.

“Currently, we are only providing trimix fills for our CCR communities,” GUE instructor Steven Millington said. “Possibly this will change, but the current direction for active technical divers is CCR. I agree (and already see) that open circuit technical diving in some regions will go the way of the dinosaur.”

In Western Europe, helium is becoming more difficult and expensive to acquire, 10 instructors in the region told us. Instructors in the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, and Germany reported longer wait times, high price increases, and limited supply.

Meanwhile, Northern Europe appears to be a bright spot on the map with comparatively reasonable prices and general availability. In Norway, two instructors reported helium is easy to obtain, with no lead time from suppliers. Likewise in Sweden and Finland, though one Finnish instructor told us that in the past year prices have increased significantly.

Three instructors in Northern Africa and the Middle East said helium is easy to get, but is becoming more expensive. The price of Sofnolime used in rebreathers is increasing in Egypt as helium becomes more expensive and more difficult to obtain. Lebanon has minimal lead times, but helium is among the most expensive in all of the responses we received at US$0.10 L/$2.83 cf.

Helium is generally easy to obtain in Mexico, though prices are increasing dramatically and instructors are starting to see delays. In Brazil, prices in São Paulo quadrupled in the past 12 months and by 30% in Curitiba. Suppliers there aren’t accepting new customers and existing customers are having difficulty obtaining supply. Supply is mostly constrained in Canada, with the exception of one outlier: an instructor who has a longstanding account with the gas company and pays less than US$ 0.035 L/$1.00 cf. “I have been hearing of helium shortage every year for the last decade,” instructor Michael Pinault of Brockville Ontario told InDEPTH, “but I have never not been able to purchase it.”

Many instructors around the world said that helium shortages and skyrocketing prices are, no surprise, fueling a shift to CCR for individual divers and exploration projects. “CCR is saving our exploration projects,” GUE instructor Mario Arena, who runs exploration projects in Europe, said. “These projects would be impossible without it.”

Please let us know what helium prices and availability are in your area: InDEPTH Reader Helium survey

Dive Deeper

US Geological Survey: Helium Data Sheet: Mineral Commodity Summaries 2021

NPR: The World Is Constantly Running Out Of Helium. Here’s Why It Matters (2019)

The Diver Medic: The Future of Helium is Up in the Air,” Everything you wanted to know about helium, but were too busy analyzing your gas to ask—talk by InDEPTH chief Michael Menduno

InDepth Managing Editor Ashley Stewart is a Seattle-based journalist and tech diver. Ashley started diving with Global Underwater Explorers and writing for InDepth in 2021. She is a GUE Tech 2 and CCR1 diver and on her way to becoming an instructor. In her day job, Ashley is an investigative journalist reporting on technology companies. She can be reached at: [email protected]