Exploration

The Swan—A 17th Century Story at the Bottom of the Baltic Sea

The Finnish dive team Badewanne has helped complete the documentary “Fluit,” about the 17th century Dutch fluyt shipwreck, The Swan, they discovered at a depth of 85 m/279 ft in the Baltic Sea in 2020. Explorer/instructor Edd Stockdale recounts the tale.

by Edd Stockdale

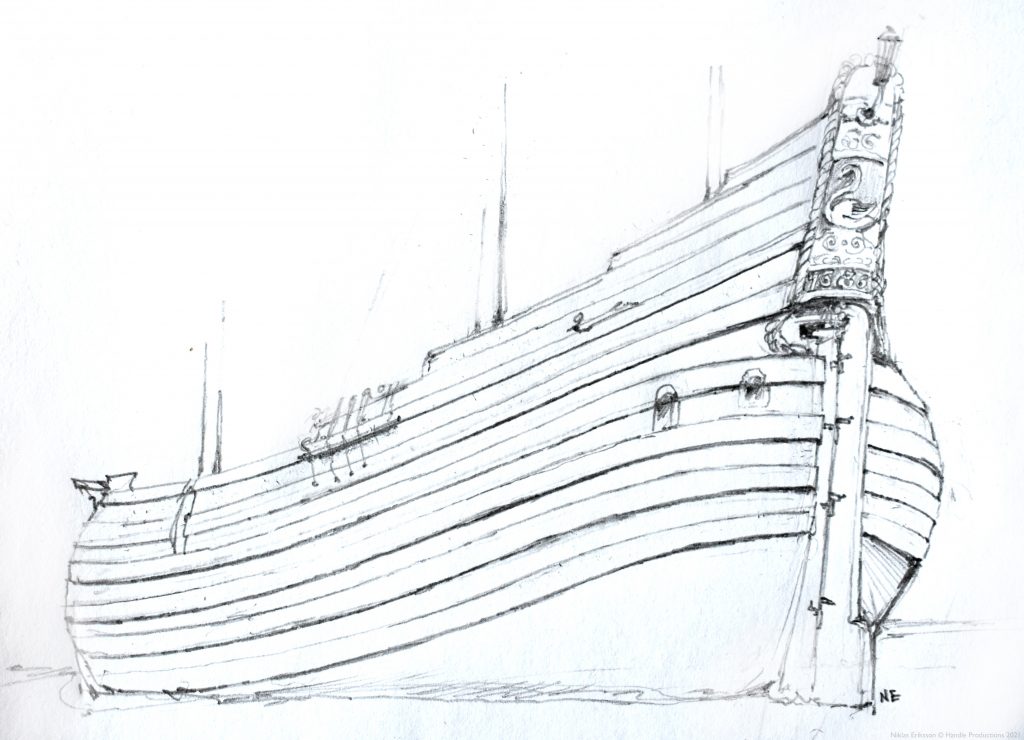

Header image: Photogrammetric 3D model of the wreck shown from starboard-bow side (ortho-metric projection). Photos by Badewanne Team, copyright Handle Productions 2021. Drawing by Niklas Eriksson copyright Handle Productions 2021

There are very few places where the preservation of shipwrecks is as good as in Baltic Sea. Due to low oxygen, cold water, low light, and absence of wood-boring organisms, the condition of ships that have sunk in these waters is extraordinary and, combined with the importance of the Baltic Sea for maritime trade, and as a site of historical conflicts, has resulted in large numbers of underwater time capsules in the form of well preserved wrecks.

The Badewanne team of volunteer divers based in Finland has for the last 20 years made it their mission to explore and document these historical shipwrecks and bring video evidence to the surface in order to share it with the general public.

Through close collaboration with researchers, heritage organisations, and governmental departments around the world, the team has found, identified, and documented many wrecks lost from the 17th century to WWII.

One such wreck was discovered in July 2020, when the team descended to 85 m/279 ft onto what they thought was a WWI minesweeper. To their great surprise and excitement, they instead discovered a 17th century vessel of Dutch fluyt built sitting upright on the bottom in an almost-intact condition aside from some trawl damage.

The fluyt design, a three-masted ship, with a very large cargo capacity for its r size, and an innovative technical design which allowed a smaller crew to man it, were highly successful vessels that increased the profitability of their voyages. Due to these features, their success hugely expanded Dutch trade throughout the world, including the Baltic Sea trading for wood, tar and hemp, as part of the merchant navy.

The original discovery in 2020 was well received by world-wide media, and the story was shared through many media channels, including Quest V 21 No.3, “Project Baseline in Finland Raises Awareness of Threats to the Baltic.” Collaborative links to continue research of the wreck were also made with maritime archaeologists Minna Koivikko from the Finnish Heritage Agency and Martijn Manders from the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, along with fluyt expert and maritime archaeologist Niklas Eriksson from Stockholm University.

In 2021, the team returned to continue research on the vessel and filming for the historical documentary film “Fluit” (alternate spelling), produced by Handle Productions, following the investigation of the origin and the mission of the fluyt, the identity of her sailors, and her untimely fate in the 17th century Baltic Sea.

As the team recorded photogrammetry footage to produce a detailed model in 2020, specific tasks were already established for the 2021 return. These included making exact measurements of specific sections of the wreck to get an accurate 3D model, searching for specific sections of the wreck, and investigating the debris field around the actual hull.

Located in this field was a specific artefact of interest, which was previously thought to be the ‘Hoekeman’ feature, a carving of strong men aimed to display the success of the merchant but, with more detailed survey, it was identified as the transom plate of the vessel, face down. This was highly exciting, as these often displayed the date of manufacture and a pictographic form of the ship’s name and as such was highly valuable for expanded insight into the history of the vessel.

After consultation with the archaeology team and careful planning of how to proceed, the transom plate was turned over to reveal both the date and a carving of a swan to the huge excitement of the team.

“The identities of ships were revealed by the carved motifs on the transom. Fragments of such motifs have been found before, but now that we have the entire composition, we are able to identify the ship in the same way as people in the 17th century did. The ship was named “Swan” and built in 1636. A closer examination of the transom will most likely reveal the coat of arms for the ship’s home port, as well,” celebrates maritime archaeologist Niklas Eriksson.

After documenting the transom plate both for video and 3D photogrammetry modelling, we began the next stage of research into this rare remaining example of what was once a hugely common ship and insight its history:

“These new findings are a great starting point to do more research. Knowing the launch year of the ship, 1636, and having an indication of the name of the ship helps us to learn more about the historical context. We may even be able to identify the people on board. The new findings also help us to learn more about the fluyt: a simple, common ship that created the right circumstances for early globalization. The fluyt highlighted the typical Dutch approach to ship building, and symbolized the flourishing seafaring trade of the time,” states maritime archaeologist Martijn Manders.

Jouni Polkko, one of the founding members of Badewanne and a leader of the team, sums it up well, “It was incredible to be the first people to see the wreck since it sank nearly 400 years ago, and now we have the opportunity to take her story up to the surface.” Twenty years of discovering and documenting un-dived wrecks in the Baltic gives an insight into the level of excitement that this work has produced as well as the opportunity to share it with the public with the Handle Production documentary.

”Fluit” is a documentary film project by Handle Productions. The film is directed by Sakari Suuronen, written by Beata Harju, and produced by Hanna Hemilä. Co-producer is Annemiek van der Hell from Windmill film, Netherlands. The diving project has been financed by i.a. the Foundation of Antero and Merja Parma and Swedish Television.

Badewanne consists of volunteer divers from different nationalities. The team specializes in documenting wrecks in the Gulf of Finland. Badewanne is also involved in research of environmental threats of shipwrecks. The divers participating in the research of the fluyt have been Jouni Polkko, Tommi Toivonen, Sam Stäuber, Jani Tattari, Ivar Treffner, Mauro Sacchi, Tiffany Norberg, Edd Stockdale, Harri Laakso and Juha Flinkman.

Edd Stockdale has worked in scientific and technical diving for over a decade and joined as Badewanne team member in 2019. He is the coordinator of the newly established Finnish Scientific Diving Academy at the University of Helsinki which was established to develop scientific diving training to further research abilities and develop new approaches to data collection in cold water based science. When not working on research diving, Edd can be found exploring the mines and wrecks in the Nordic region or planning the next adventure. He is supported by Divesoft as well as Santi, Halcyon, and REEL Diving in Scandinavia.