Cave

The Taming of the Slough: P3 Edition

Explorer Steve Lambert reports on the latest exploration push at Peacock 3, aka P3, in Wes Skiles Peacock Springs State Park, enabled by long range scooters, CHO2ptima rebreathers, electric heat, and a deco habitat with scrubber. Having teamed up with Karst Underwater Research (KUR), Lambert and friends have now pushed P3 penetration to 2286 m/7500 ft, at depths to 61m/200 ft with run times in excess of 5-6 hours. Scoop that booty!

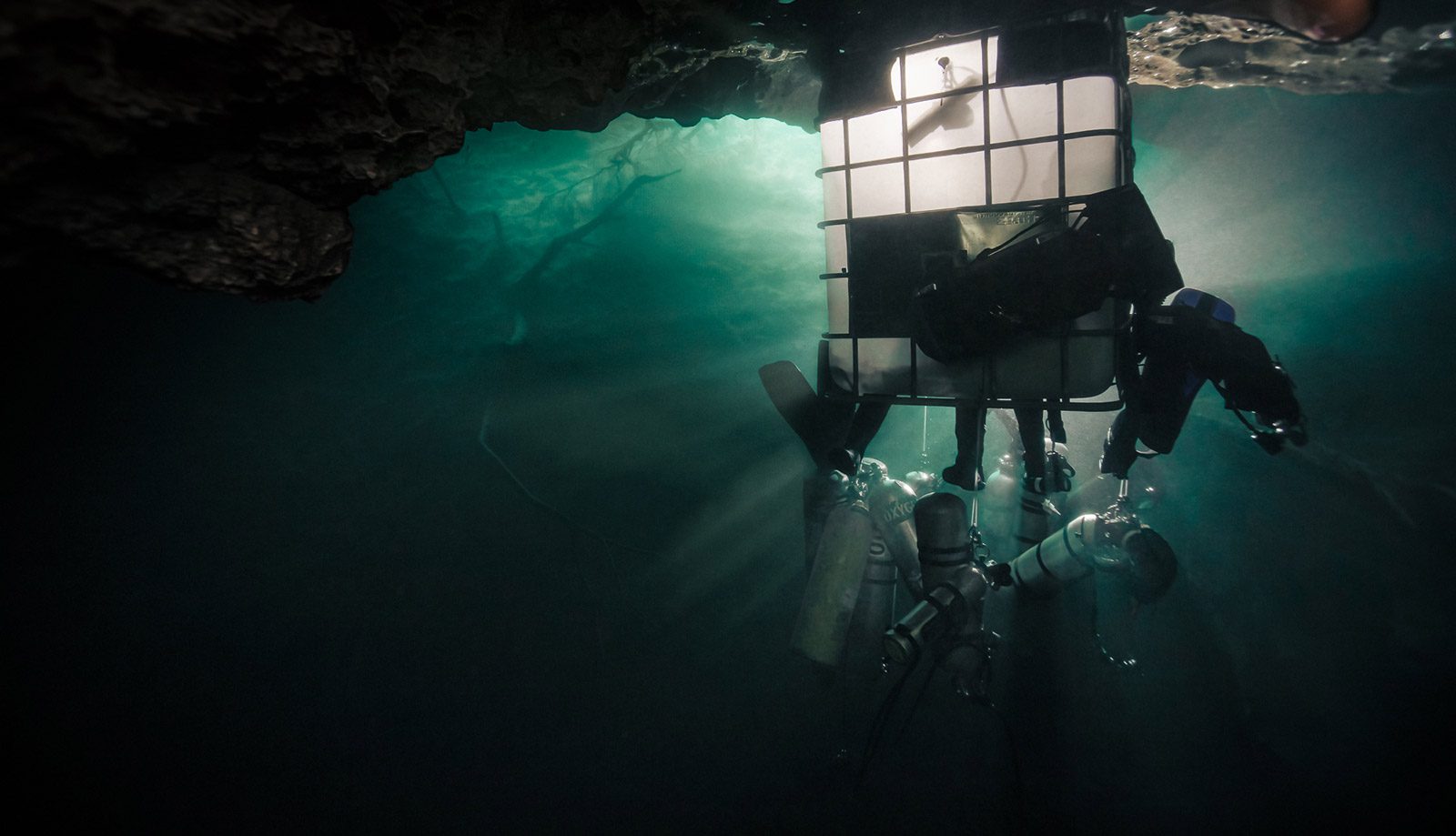

By Steve Lambert. Header image: P3 deco habitat at 6m/20 ft by Fan Ping. Images courtesy of Steve Lambert unless noted.

Peacock Springs in North-Central Florida is almost synonymous with cave diving. Since the dawn of the sport, divers have been exploring the beautiful blue sinks that now make up Wes Skiles Peacock Springs State Park. Many of the household names in cave diving took part in the exploration of the system in the 60s and 70s, and even more well-known names did the full survey in the 90s. The last significant exploration was done in 2010, when Agnes Milowka and James Toland connected the system with Baptizing springs, adding over 3,084 m/10,000 ft to the total length of the system.

My first experience with Peacock 3 (P3) was during my full cave course with Reggie Ross, the former training director for the NSS-CDS. I stood near the system map tucked in the corner of the Peacock 1 (P1) parking lot, shivering in my 5 mm wetsuit and kicking myself for being too cheap to fork over the money for a drysuit while listening to Reggie explain what to pay attention to while diving a siphon. I vividly remember the deep tunnel sticking out to me, thinking it didn’t belong with the rest of the park. It was strange to me that a system so big would have such a drastic and seemingly random change in depth. Of course, at that time, I didn’t have a “feel” for what caves do. I just thought it was strange.

Several years later, in May of 2019, Paul Heinerth and I decided to go for a dive past the restriction at the bottom of Hendly’s Castle. Paul said he hadn’t been back there in years, and it sounded like an intriguing dive to me. Coincidentally, that morning we ran into James Toland while gearing up in the parking lot. He had the end of the line in the deep section and shared with us how to navigate through the restriction and what to expect in the passage below. When I curiously asked him why he turned when he did, he said he wasn’t able to see because of how silty the area was.

Using Sidewinder rebreathers and trimix, Paul and I swam down to the bottom of Hendly’s Castle and, thanks to James, we were able to find our way through the restriction and into the lower section. The passage was stunning. Incredible Goethite formations blanketed the ceiling, like nothing I had ever seen. Intensified by the subtle narcosis overtaking me, I was awestruck at the unique features of the passage. We swam at an enjoyable pace, assisted by the slight siphon. I was floating along the line with Paul just behind me, soaking up every second of the dive, when all of a sudden I was greeted by a “Saber” arrow at the end of the line.

I was in disbelief that we had reached such a remote place so easily and unintentionally. Suddenly, James’s words stuck out to me—“because I couldn’t see.” I was hovering there, and I could see. A decompression penalty was piling up and I knew I couldn’t stay long, but I could not pass up the opportunity. I scrambled to tie in my safety reel and set off. James had tied off at what seemed like the end of the passage with the right side tapering off into mud, but the left side looked promising. The flow had to be going somewhere.

I headed off toward the left where there was a breakdown pile. The silt I knocked up seemed to be sucked into it. I could tell that was where the water was going. As the adrenaline of seeing something new coursed through my veins, I decided to “modify” a few things and see what was going on. I shoved a few pieces of breakdown to the side, stirring up clouds of fine clay silt but opening up a space just big enough to fit my head and shoulders into. I saw black. A hill was sloping upward and above it was only darkness. I wiggled forward, but the scrubber cans of my sidewinder prevented me from getting any further. The silt was beginning to obstruct my view, and I watched as the promise of finding something new was overtaken by a gray cloud of silt.

Suddenly fear started to creep into my mind—that little voice that says, “think about how far you are from home, and now you are in zero vis in a passage you aren’t familiar with.” Excitement morphed into fear, and I quickly spooled up my safety back to the main line, in a hurry to be back to where I could see Paul. We swam back to the cavern and swam in circles to stay warm as we did our deco. The dive was 5 hours and 45 minutes. I finished cold and tired, but excited for the potential of what might lie beyond the breakdown.

My Return to P3

During the two years before I returned to P3, that darkness was always in my head. I tried getting several buddies to come with me to take a second look at the area, but my story wasn’t convincing enough to get lazy divers to “swim like a peasant” in a place where DPVs are not allowed. During these two years an important piece of this story was born, Dive Rite created the chest mounted CHO2ptima rebreather.

In April of 2021 I was finally able to find a diver who feared neither deco nor swimming; Zeb Lily was in town and I conned him into going with me. Not sure if I had embellished my own memory in the past two years, I anxiously swam back to the breakdown choke. I could see the black hole where I had “adjusted” several large rocks on the previous dive. I persuaded a few more pieces of breakdown to identify as positions to the right and left of their natural state, and with my CHO2ptima, I was able to squeeze through. While in the breakdown, I could feel the flow intensifying and continued to wiggle forward, trying my best to stay ahead of the silt cloud I was creating. At the same time I was memorizing the shape of the passage so I would not panic while trying to find my way back through the restriction in bad visibility.

The moment I popped out into an absolutely massive room was surreal. Visibility was markedly better than in the passage, and the temperature was noticeably warmer. Even with the improved visibility, from right to left my light did nothing to penetrate the darkness, and I was following an upward slope into the unknown. It was one of those rare moments when exploration goes exactly how you want it to. Instead of pinching off in some sort of death trap, the cave went onward. I savored the moment and did my best to find the way on, but the passage was so massive I was disoriented. I swam in a zig zag until my reel ran out of line, and tied off at 41 m/135 ft on the left wall of what seemed like a massive debris cone.

I surveyed out and Zeb and I exited, ecstatic that we had found something new in such a thoroughly explored system. Once again I thought of what James Toland had said when he and Milowka connected Baptizing to Peacock back in 2010. “Many divers from the Florida cave diving community are focusing on exploration around the world, but I think it’s important to focus on exploration in our own backyard – a little something I like to call tailgate diving,” he said. “There is still a lot of cave here waiting to be pushed, and with the evolution of dive gear and divers alike comes the ability to do deeper and longer dives. This opens up new and exciting opportunities that were overlooked or never considered in the past.”

More Cave To Go

After Zeb and I discovered that the cave continued, I ramped up my efforts to recruit buddies for exploration at P3. On the next dive, we continued from where I had tied off at the top of the 41 m/135 ft mound and continued downward, back to 55 m/180 ft, where a spring vent was coming out of the wall. I remembered having heard people speculate that Lower Orange Grove was tied to P3, and was very excited. The entrance was too small to go into without advanced planning, so we tied off and surveyed out from there, but the springing passage certainly had our attention.

On the way out of the massive room, while going back through the breakdown restriction, I noticed that the flow from the newly discovered room and the flow form the previous EOL was combining, and going off in a different direction through the breakdown. I quickly grabbed my reel, and proceeded to empty it into the siphoning passage. I turned the dive with an empty reel and safety spool, extremely excited that we had located the continuation of the siphon, and ended in a large passage. The next dive was going to be good.

The next dive was one of the best I’ve ever had. Adam Hughes and I arrived as the gate to the park opened, and we pushed off shortly after. Worried about what kind of decompression obligation we might encounter, we swam along the 61 m/200 ft passage as fast as possible. Arriving at the end of the line in a borehole passage, we soaked up every moment, as it is a rarity in modern Florida cave diving. We slowed down to a relaxed pace and savored each foot of line that emptied off of our reels. We navigated through a large bedding plane and ended up in a springing passage. The visibility was perfect, but the passage seemed to get smaller and smaller. Eventually we had to tie off, realizing that the passage was probably an in feeder, and not the continuation of the siphon. We surveyed out and completed our decompression for a six and a half hour dive.

We started our next dive beelining for the EOL. Right before the spring vent, we found where the siphon continued on. We tied in and once again slowed down to enjoy the exploration. The passage was big, and the flow was strong. In a few fleeting moments of perfection, line fell off the exploration reel effortlessly, as the siphon pulled us deeper into the earth. After 244 m/800 ft had disappeared, the passage once again seemed to pinch off. Following the flow seemed to take us to a hole in the ceiling, once again pinched off by breakdown.

We pushed and pulled, and rocks began to drop down on our heads. The hole was about 0.6m/2 ft wide, and after a decent workout, we had a mound of large rocks under the hole. I poked my head up and could fit my shoulders through, but because of our “modifications” the visibility was reduced to almost zero. I felt with my hands, and it seemed like once again we had broken into a room, and I was excited to come back to confirm our findings. The increasing flow of the siphon made the journey back to the cavern quite difficult, and I began to realize that at around 1,372 m/4,500 ft of penetration at 55-61 m/180-200 ft of depth, we had come close to the limit of what was possible on a swim dive. Our lungs burned from the hard work we were doing at depth, as well as the long exposure to high PO2. We were going to need help.

A Little Help From My Friends

I had been talking to Brett Hemphill with Karst Underwater Research (KUR) about the new find, and after explaining our situation, we decided it was time to put the project under the KUR permit. The permit would allow us to continue the exploration and documentation of the system while utilizing more tools to increase our safety and efficiency. The permit would also allow us to stay in the park after hours, as the dives were getting to a length that did not allow us to complete them within the regular park hours.

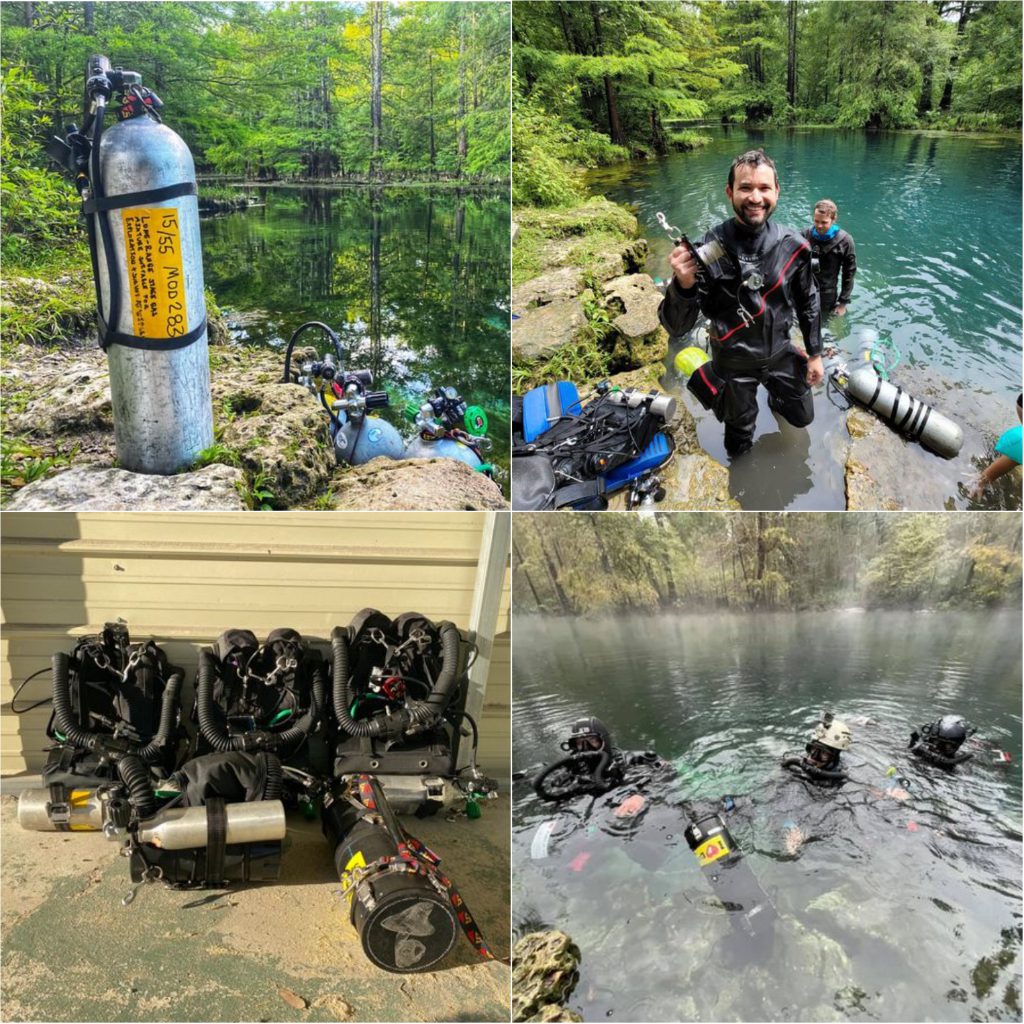

Having the backing of KUR, and the tools that come with it, we were able to make quick progress of the exploration. Jefferson Marchand was back in town from the Dominican Republic, and the two of us made the project our priority, diving every weekend we were able. While some dives ended with confusion, most of them ended with empty reels and smiles.

The cave alternates between borehole passage and large dome rooms choked by breakdown. The passage is mostly in the 58 m/190 ft range, and the tops of the debris mounds in the rooms usually go to around 46 m/150 ft. Each time a room is encountered, divers have to wiggle through breakdown restrictions to get both in and out of the room, which makes the dive technically challenging, especially considering the amount of equipment required to be carried by the divers.

There comes a point when a dive has such unique challenges that equipment doesn’t exist to meet them. Luckily, KUR has more than a decade and a half of experience with these kinds of problems, so Jefferson and I were able to draw on their experience to develop solutions and keep exploring. We bought a 1364 l/300 gallon intermediate bulk carrier (IBC) container and turned it into a habitat, which Brett Hemphill helped us to install in the cavern.

With help from Andy Pitkin, Matt Vinzant, and Daniel Vickers, we built a habitat scrubber, which made the long decompressions much safer. It had the added benefit of allowing us to remove all of our equipment and relax while staying warm. In the habitat we could eat, drink, watch movies, and chat. We also created very large battery packs in case of a flood during the in-water portions of the deco and a two-way telephone system that allowed easy communication between divers and surface support.

Dive Rite was a very big supporter of the project. Our equipment was built with the aid of their facilities, and in addition to sponsoring much of our gas, they helped with scooters, staged rebreathers, and regulators for safety bottles as well. It would not have been possible for us to acquire the massive amount of equipment necessary for the exploration without their help.

| “The current end of line is around 2,286 m/7,500 ft. At the peak of our efforts, we had over 20 safety bottles staged in the cave and the dives were running up to 12 hours—even with a relatively aggressive profile.” |

Unfortunately, Jefferson had to return to the Dominican Republic, and things I had been putting off were catching up to me, so progress came to a temporary halt. We were also having trouble with our staged safety bottles in the back of the deep section corroding much quicker than expected. We lost gas due to corrosion in several bottles after only three months.

During this pause, we have been formulating a plan to deal with the increasing demands of the dive. This summer of 2022 we are gathering a group of people who have the experience on sidemount rebreathers to do such a challenging dive, and who will commit to the project. We are also hoping to prepare a second habitat to put somewhere around Hendly’s Castle to further increase our safety margin.

We will be making further attempts to locate the resurgence in the river and push from that end. As the crow flies, there is still almost 2438 m/8000 ft between our end of line and the river, and caves usually don’t go in straight lines. No matter what happens, it is going to be a massive undertaking and will require a full team of push divers and support divers to make the project a success.

Just like in the 90s when Mark Long was the first person able to explore the system, because he was the first to have tanks big enough to give him the required gas for such an extreme dive, we were only able to continue exploration in this section because of the current diving technology including; long range scooters, removable chest-mount rebreathers, habitats and habitat scrubbers, dry suit heat, waterproof tablets for entertainment, and last but most certainly not least, reliable dive computers that can accommodate multiple gasses and adjustable algorithms was available to us.

I shudder to think about how little cave might be left in Florida if Woody Jasper and the other incredible explorers who came before us, had access to the equipment we are using today.

I shudder to think about how little cave might be left in Florida if Woody Jasper and the other incredible explorers who came before us, had access to the equipment we are using today. If all goes well, we will use the incredible tools we have access to today to push the cave until the connection to the river is confirmed.

Dive Deeper:

Ezine Articles: The Taming Continues: The Peacock to Baptizing Connection by Agnes Milowka & James Toland

Cavesurvey.com: Peacock Springs

NSS-CDS bookstore: THE TAMING OF THE SLOUGH – HISTORY OF PEACOCK SPRING by Sheck Exley

Steve Lambert lives in North Florida where he works at Dive Rite and is actively involved in the exploration and survey of underwater caves with Karst Underwater Research. He frequently joins expeditions with Beyond the Sump and Hole Patrol. His hobbies include quitting when things get too hard, residential construction, and compiling Kpop playlists.