Education

The Thought Process Behind GUE’s CCR Configuration

Global Underwater Explorers is known for taking its own holistic approach to gear configuration. Here GUE board member and Instructor Trainer Richard Lundgren explains the reasoning behind its unique closed-circuit rebreather configuration. It’s all about the gas!

By Richard Lundgren

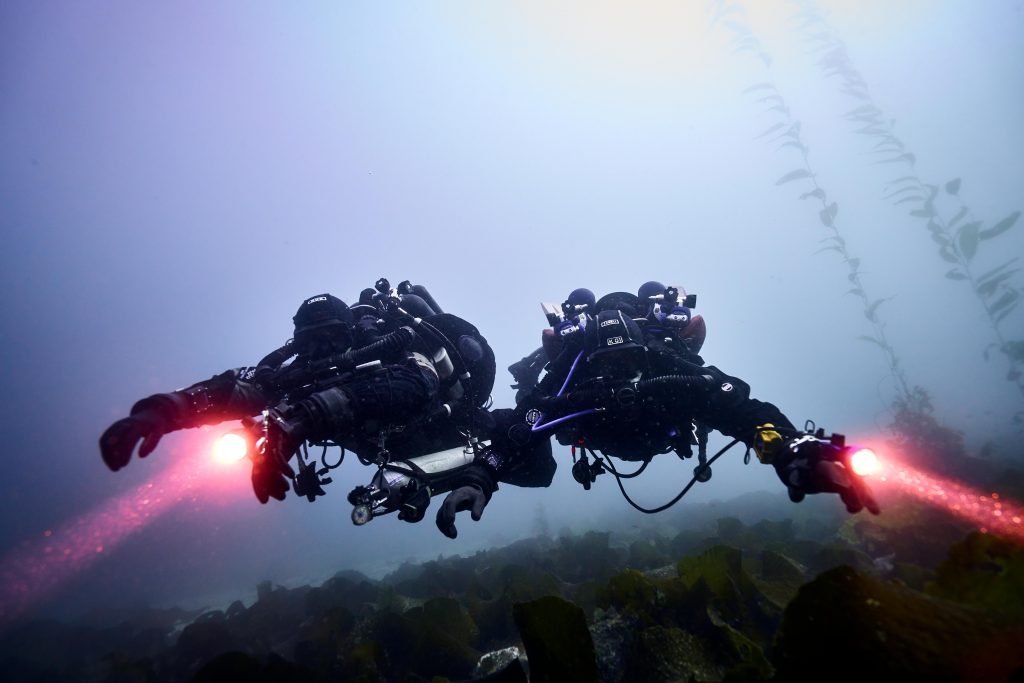

Header photo by Ortwin Khan

Numerous incidents over the years have resulted in tragic and fatal outcomes due to inefficient and insufficient bailout procedures and systems. At the present time, there are no community standards that detail:

- How much bailout gas volume should be reserved

- How to store and access the bailout gas

- How to chose bailout gas properties

Accordingly, Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) created a standardized bailout system consistent with GUE’s holistic gear configuration, Standard Operating Procedures(SOP), and diver training system. The system was designed holistically; consequently, the value and usefulness of the system are jeopardized if any of its components are removed.

Bailout Gas Reserve Volumes

The volume of gas needed to sustain a diver while bailing from a rebreather is difficult to assess, as many different factors impacts the result— including respiratory rate, depth and time, CO2 levels, and stress levels. These are but a few of the variables. All reserve gas calculations may be appropriate under ideal conditions and circumstances, but they should be regarded as estimates, or predictions at best.

The gas volume needed for two divers to safely ascend to the first gas switch is referred to as Minimum Gas (MG) for scuba divers. The gas volume needed for one rebreather diver to ascend on open-circuit during duress is referred to as Bailout Minimum Gas (BMG). The BMG is calculated using the following variables:

Consumption (C): GUE recommends using a surface consumption rate (SCR) of 20 liters per minute, or 0.75 f3 if imperial is used.

Average Pressure (AvP or average ATA): The average pressure between the target depth (max depth) to the first available gas source or the surface (min depth)

Time (T): The ascent rate should be according to the decompression profile (variable ascent rate). However, in order to simplify and increase conservatism, the ascent rate used in the BMG formula is set to 3 meters/10 ft per minute. Any decompression time required before the gas switch (first available gas source) must be added to the total time. One minute should be added for the adverse event (the bailout) and one minute additionally for performing the gas switch.

BMG = C x AvP x T

Note that Bailout Minimum Gas reserves are estimations and may not be sufficient! Even though catastrophic failures are unlikely, other factors like hypercapnia (CO2 poisoning) and stress warrants a cautious approach.

Decompression bailout gas volumes are calculated based on the diver’s actual need (based on their decompression table/algorithm), and no additional reserve is added.

It should be noted that GUE does not endorse the use of “team bailout,” i.e. when one diver carries bottom gas bailout and another diver carries decompression gas based on only one diver’s need. A separation or an equipment failure would quickly render a system like this useless.

Common Tech Community Rebreather Configuration

- Backmount rebreather (note side mount rebreathers are gaining in popularity)

- Typically, three-liter oxygen and a three-liter diluent cylinder on board (each hold 712 l/25 f3)

- Bailout gas in one or more stage bottles which could be connected to an integrated Bailout Valve (BOV).

Containment and Access

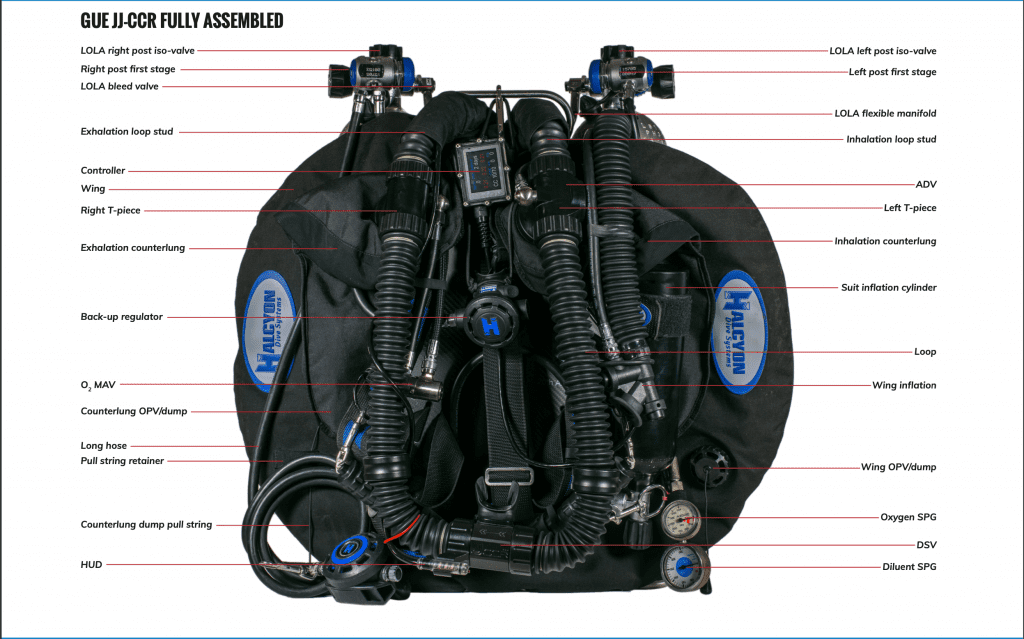

Rather than carry bailout minimum gas (BMG) in a stage bottle, which is typical in the rebreather diving community, GUE has designed its bailout system as a redundant open-circuit system consisting of two 7-liter, 232 bar cylinders (57 f3 each) that are integrated into the rebreather frame, and called the “D7” system, i.e. D for doubles, 7 for seven liter. Note that GUE has standardized the JJ-CCR closed-circuit rebreather for training and operations.

These cylinders, each with individual valves, are linked together using a flexible manifold. This system holds up to 3250 liters of gas (114 f3), of which only about 10% is used by the rebreather as diluent. Hence, close to 3000 liters (106 f3) is reserved for a bailout situation. This gives a tremendous capacity and flexibility in a relatively small form factor for dives requiring additional gas reserves (when direct ascent is not possible or desirable).

The following advantages were considered when designing the bailout system:

- The D7 system is consistent with existing open-circuit systems utilized by GUE divers. A bailout system that is familiar to the user will not increase stress levels, which is important. A GUE diver will rely on previous experience and procedures when most needed.

- The system contains the gas volumes needed according to the GUE BMG calculations as well as the diluent needed for a wide range of dive missions.

- The system is fully redundant and has the capacity to isolate failing components, like a set of open-circuit doubles and still allowing full access to the gas.

- The overall weight of the system is less, compared to a standard system with an AL11 liter (aluminum 80 f3) bailout cylinder. In addition, it contains 800-900 liters/20-32 f3 more gas available for a bailout situation compared to the AL11 liter system. Weight has been traded for gas.

- The system does not occupy the position of a stage bottle which allows for additional stages or decompression bottles to be added.

- If the ISO valves on each side were closed, the flex manifold can be removed and the cylinders transported individually while still full.

Bailout gas can be accessed quickly by a bailout valve (BOV), which is typically configured as a separate open-circuit regulator worn on a necklace, consistent with GUE’s open-circuit configuration. However, some GUE divers use an integrated BOV. After evaluation of the situation, while breathing open-circuit from the BOV, the user can transition to a high-performance regulator worn on a long hose if the situation calls for it.

The long hose is carried under the loop when diving the rebreather. The chances of having to donate to another GUE rebreather diver is low, as both carry redundant bailout. Still, GUE maintains that the capacity to donate gas must be present. The process is more likely to involve a handover of the long hose rather than a donation.

Still, if needed, such a donation is made possible by either removing the loop temporarily or by simply donating the long hose from under the loop.

Bailout decompression gasses are carried in decompression stage bottles. If more than three bottles are needed, the bottles that are to be used at the shallowest depths are carried on a stage leash (i.e. a short lease that clips to your side D-ring to carry multiple stage bottles). Maintaining bottle-rotation techniques and capacity through regular practice is important and challenging, as this skill is rarely used with the rebreather.

Bailout Gas Properties

The choice of bailout gas is extremely important, as survival may well depend on it. It is not only the volume that is important, the individual gas properties will decide if the bailout gas will be optimal or not. As the D7 system contains both the diluent and bailout gas, both gasses share the same characteristic. The following gas characteristics must be considered when choosing gas:

Density

The equivalent (air) gas density depth should not exceed 30 meters/100 ft or 5.1 grams/liter. This is consistent with the latest research by Gavin Anthony and Simon Mitchell that recommends that divers maintain maximum gas density ideally below 5.2 g/l, equivalent to air at 31 m/102 ft, and a hard maximum of 6.2 g/l, the equivalent to air at 39 m/128 ft. You can find a simple gas density calculator here.

Ventilation is impaired when diving, due to several factors which increase the work of breathing (WOB); when diving rebreathers, the impairment is even more so. High gas density, for example, when diving gas containing no or low fractions of helium, significantly decreases a diver’s ventilation capacity and increases the risk of dynamic airway compression. CO2 washout from blood depends on ventilation capacity and can be hindered if a high-density gas is used. The impact of density is very important, and the risk of using dense gases is not to be neglected. Note that this effect is not limited to deep diving. Using a dense gas as shallow as 30 meters/100 ft reduces a diver’s ventilation capacity by a staggering 50%.

Narcosis

The (air) equivalent narcotic depth should also not exceed 30 m/100 ft, or PN2=3.16. Rebreathers and emergency situations are complex enough without further being aided by narcosis.

Oxygen Toxicity

The PO2 should be limited to allow for long exposures. GUE operating standards call for a maximum PO2 for bottom gases of 1.2 atm, a PO2 of 1.4 for deep decompression gases, and a PO2 of 1.6 for shallow decompression gases. GUE recommends using the next deeper GUE standard bottom gas for diluent/bailout when diving a rebreather in combination with GUE standard decompression gases.

Bailout gasses are not chosen in order to give the shortest possible decompression obligation. They are chosen in order to give the best odds of surviving a potentially life-threatening situation.

In Summary

GUE’s D7 bailout system is flexible and contains the rebreather’s diluent as well as bailout gas reserves needed for a range of different missions. The familiarity the system, along with the knowledge that they are carrying ample gas reserves, gives GUE divers peace of mind. Choosing gases with properties that will aid a diver in duress while dealing with an emergency completes the system.

GUE did not prioritize the ease of climbing boat ladders or reducing decompression by a few minutes. These are more appropriately addressed with sessions at the gym, combined with finding aquatic comfort. Nothing prevents a complete removal of the entire system at the surface if an easy exit is needed.

Founder of Scandinavia’s Baltic Sea Divers and Ocean Discovery diving groups, and a member of GUE’s Board of Directors and GUE’s Technical Administrator, Richard Lundgren has participated in numerous underwater expeditions worldwide and is one of Europe’s most experienced trimix divers. With more than 4000 dives to his credit, Richard Lundgren was a member of the GUE expeditions to dive the Britannic (sister ship of the ill-fated Titanic) in 1997 and 1999, and has been involved in numerous projects to explore mines and caves in Sweden, Norway, and Finland. In 1997, in arctic conditions, he performed the longest cave dive ever carried out in Scandinavia. Richard’s other exploration work has included the 1999 filming of the famous submarine, M1, for the BBC; the side scan sonar surveys of the Spanish gold galleons outside Florida’s Key West in 2000; and the search for the Admiral’s Fleet, an ongoing project that has already led to the discovery of more than 40 virgin wrecks perfectly preserved in the cold waters of the Swedish Baltic Sea.