Cave

Thoughts on Diving To Great Depths

By Jim Bowden, March 7, 1998

Header image: Explorer Jim Bowden surveys Zacatón. All photos courtesy of Jim Bowden and Proyecto de Buceo Espeleologico Mexico y America Central

Deeper into, the abyss, knees bent and streamlined for speed. The feeling of space and the suspicion that the void goes on and on. The darkness closes in, embraces me, not hostile, not threatening, just black like eternity. My light, a sword with nothing to touch, only my line, and the limits that my fears decree.

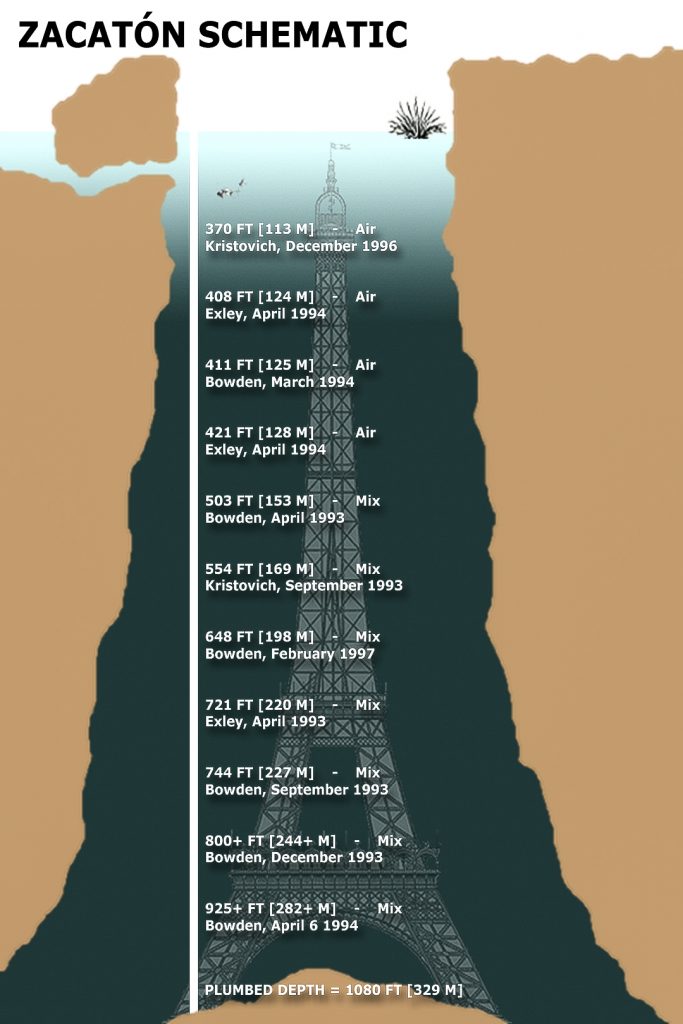

These last few years I have wondered about my comrades in arms who have experienced that immersion into great depths. In 1993, Sheck Exley published an article in aquaCORPS # 7 C2 titled, “Beyond 500 feet (150 m)” listing sub-500 ft/153 m open circuit technical dives. There were thirteen at the time, completed by six divers, five men and one woman. All but one were in fresh water and in caves, though Exley commented that the wreck divers were sure to ”catch up.” Other than general fatigue, and one case of skin bends, no DCS symptoms were reported. The decompression models used were customized and often proprietary. My intention here is to update the list of sub-500 ft dives/153 m. To date, at least thirty-seven have been completed in this range and technical diving is no longer the realm of the lunatic fringe, at least in comparison to a few years ago. This paper will embrace the sub-500 ft/153 m dives made to the present and the known physiological challenges to those who dare. At best, it is an incomplete report and it will be dated by the time it finds print. The participants are not always forthcoming with all the details of their activities (myself included) and not all the individuals involved in these dives are known. Not everyone is interested in sharing their passion with the world. It is an immensely personal endeavor whether they chose media coverage or not.

The dives in the chart Deep Dive List (1982-1998) [See: Diving Beyond 250 Meters] reflect the historical journey rather than a listing of progressively greater depths. To list them according to depth would imply a status that deeper is the greater accomplishment. The deepest depth is a coveted goal and I cannot exclude myself in this desire. However, some of these dives, such as Jochen Hasenmayer’s (sneak) dive in Vaucluse, Nuno’s difficult access and altitude, the cold and strong currents that some of the wreck divers must face, makes the distinction that just the volume of water over one’s head is a poor gauge of the individual’s accomplishment. It must be considered that many of these dives were preparation dives for a much more ambitious effort in the future. In Sheck’s article, I was one of the six divers in the sub-500 ft/153 m group. I was honored to be there. In less than six months I had made two more dives and found myself with the record. This is waiting to happen on the world scene. Somewhere someone—South African, French, German, Swiss—is on the brink of accomplishing the impossible.

DEEP DCS

Diving at the edge of the envelope obviously invites the possibility (probability) of decompression illness. “Bends is a statistical inevitability” says Bret Gilliam. The true pioneers in this exotic discipline were extremely exposed. Jochen Hasenmayer and Sheck Exley had little history to guide them in their efforts. Decompression software and models that would fit their particular techniques were not available, and everything was experimental. We have all benefited from their courage and their accomplishments.

It is remarkable, considering the extreme nature of the dives, that there have been few incidents of DCS among the divers listed. The inert gas exposure facing each of these individuals is mind boggling, and the lack of CNS compromise in this series of dives is interesting. Jochen’s unfortunate incident occurred because of the cascading number of mistakes brought about by equipment malfunctions; he was also subject to inappropriate recompression treatment. My hit was multiple joint involvement, Nuno’s was inner ear, Gilberto’s was, by his report, the result of poor choices in the decompression profile. We have all recovered and are still diving aggressively.

Complicating the risk of DCI and the hope of resolution of symptoms is the remoteness of many of the dive sites. Nature is seldom kind enough to grant us sites that provide ease of excavation and treatment. In water recompression and/or aggressive medical management in the field are often the only options available for immediate DCI management.

High Pressure Nervous Syndrome

Sheck experienced HPNS on his August 1993, 863 ffw/265 mfw dive in Bushmansgat, SA. It occurred below 700-750 ffw/215-230 m. Descending at greater than 100 fpm/30 mpm, he first experienced visual disturbances at or just below 700 ft/215 m. His entire field of vision became a series of small concentric circles with black dots in their centers. Distant vision deteriorated, and objects began to blur. He slowed his descent and paused at 750 ft/230 m in the hope of relieving the problem. Around 800 ffw/245 m he experienced itching all over his body that soon became a stinging sensation (Inert gas counter diffusion?). Tremors ensued and increased in intensity until he reached the bottom at 863 ffw/265 m. According to Sheck, ”the tremors were quite intense by the time I reached the bottom, severe enough to make operation of my inflator difficult. Essentially, the bottom stopped the descent. My entire body began trembling, gradually escalating to uncontrollable shaking by the time I landed.” On ascent, all of his symptoms disappeared by the time he reached 400 ffw/123 m.

Interestingly enough, Sheck did not experience HPNS during any of his dives in Mante, all of which were in excess of 500 ft/153 m (see chart below). His descent rate was slower than the 100 fpm/30 mpm rate in Bushmansgat due to the current, but still very fast compared to commercial protocol. He mentioned no problems with his 721 ffw dive in Zacatón in which his rate of descent was greater than 100 fpm. I dove with him that day, and I am sure he would have mentioned it. We were planning our future dive to the bottom of Zacatón, and we discussed every aspect of our plans and concerns. Sheck called it “addressing our fears.” Very appropriate and necessary on dives of this magnitude.

Nuno Gomes reported on all his dives to 581 ft/178 m and on his recent dive to 925+ ft./284m. Nuno has made at least two other dives in excess of 500 ft, one to 754 ft/231 m and the other to 826 ft/253 m. I have no information revealing that he experienced HPNS on those dives. On his deepest dive he experienced tremors beginning at 600 ft/184 m but felt comfortable continuing his dive. “I had felt this before; therefore, I was not alarmed,” Nuno said.

Gilberto Menezes de Oliveira, diving Agua Milagrosa in Brazil, experienced slight trembling in his left arm which he presumed was HPNS. It occurred as he approached 500 ffw/153 m. He later made another dive to 592 ffw/182 m m the same system and did not experience HPNS.

Out of dives to 504, 648, 744, 800+ and 925 feet, I have experienced what I perceived to be HPNS on only one dive. On the dive to 800+ ffw/245 m I experienced tremors in my latissimus dorsi and my arms. It was noticeable but not serious enough to abort the dive. It occurred around 700 ft/215 m. I had been ill with the flu just prior to the dive. Other deep colleagues, Dr. Ann Kristovich, Terrence Tysall, and Mike Zee have not mentioned any problems with HPNS.

HPNS can occur as it pleases. Immunity one day does not insure that it will not occur on a subsequent dive. In some cases it can be mild enough to be tolerated. On brief technical dives, perhaps the worst effects of HPNS—nausea, vertigo, and convulsive jerking—would not take place. Without the saturation habitat environment used by commercial divers, the occurrence of these types of symptoms would probably be fatal.

The whole concept of diving for records carries emotional responses that often confound and confuse the explorer/adventurer. The desire to excel in some way is a powerful drive that has existed since the beginning of civilization. Usually a solitary and driven individual, divers who find themselves suddenly thrust into their 15 minutes of fame, also find themselves both respected and vilified. Not only in diving to extreme depths but in almost all extreme sports the accomplishment of the task carries the burden of attention, both positive and negative. Divers who are kindly labeled pioneers, and brave adventurers are also labelled thrill seekers, insecure individuals seeking attention, and just plain crazy.

The situation is further confused by the public desire for a champion. I think this is more of a European thing than here in the states. Competition becomes a factor. Accomplishments are often segmented to allow for champions in methods and degree of risk: a different, more difficult route climbed, a breath-hold dive made without assistance, or with assistance either on descent or ascent or freestyle. The media stokes the fire with the promise of a future story. In 1993, it was a simple catalogue of divers who made dives to deeper depths. Now there is talk of having different categories.

My dialogue with divers throughout the world in researching this article revealed proposals that range from some degree of practicality to the absurd. Suggestions have come from the European community about categorizing records by scuba or surface supplied, requirements that all decompression gases be carried by the diver, the diver must have no help from the surface, extra tanks can be available but the diver cannot use them (I presume you could in an emergency). Other styles would allow surface support, deco gases hanging on a line, habitat use, heating, and so on. There is no “official” delineation but there is a trend in that direction. Perhaps this is inevitable. Already there are claims based on experts assessing the depth reached by the severity of HPNS symptoms. Give me a break.

Nuno had HPNS on his shallowest sub-500 ft/153 m dive, look what he has done since. I had HPNS on my 800+ ft/245 m dive, but no noticeable symptoms on my dive 125+ ft/37 m deeper. When there’s talk about depths of 500 ft/153 m and greater, there is a difficulty of accurately recording the depth with existing technology. Already there have been mathematical calculations based on environmentally difficult premises. Sheck was never happy with the need to calculate his record depth at Mante. Allowing for errors, he estimated the depth of his dive between 867 ft to 880 ft/266-270m. Ever modest, he personally chose the lesser number. He wrote that his 863 ft/265 m dive in Bushmansgat was just four feet shy of his record. Those of us who admired him chose the latter.

Dr. Kristovich, out of respect and admiration for M. E. Eckhoff [Sheck’s widow], stated that she would not claim the woman ‘s record unless it was decisive. At 554 ft/170 m, her dive surpassed the record by 154 ft/47 m, but if it had been less than 100 ft greater/30 m, she wouldn’t have claimed it. I believe her. So the whole vague, confusing and admirable issue of personal ethics clouds the question as well.

The depth of my dive was determined by the UWATEC computer I sent to the media representatives waiting for me to finish my greater than ten hours of decompression. Concerned and desperate to arrest my descent because of inadequate gas volumes to continue the dive, the 925 ft/283 m marker on the descent line passed through my hand. Where did I stop? Who knows? I was desperate to get out of there. The writer from Sports Illustrated and Discover Magazine chose my depth for me from the read out on the UWATEC, 925 ft/283 m. At the time, I was shocked and grief stricken over the loss of Sheck. It was hardly a time for rejoicing. For the next year both the criticism and the loss of my friend did not allow me to accept the fact that I had made a ”record” dive.

Nuno is the man of the time in my opinion. I will not concede that he went deeper, but if he had not bottomed out Bushmansgat, then he would have been the first man to make a sub-300 m dive. Nuno and I both have done more sub-500 ft dives than anyone else in the world. As fortune would have it, we are tied in that number. Fate is fickle and a tie carries about as much excitement as kissing your sister. The public and the media cry for a decisive champion. If succumbed to, then that pressure can kill you. I hope that we are both too smart for that.

Unfortunately, some of us will die in pursuit of great depth. The continued efforts in the face of danger is unanswerable to anyone but the participants. I do believe that every man and the one woman here would agree that the intense freedom of the now, a moment that is unique and life enhancing and the pushing oneself in order to find oneself is, indeed, a reaffirmation of life.

My colleagues, I salute you. We are brothers and sisters of a kind. A bond of having been in the belly of the beast. No one can understand who hasn’t been there.

Return to the main story: Diving Beyond 250 Meters