Exploration

U-1105: The Black Panther, The World’s Most Accessible U-Boat

Explorer and maritime historian Erik Petkovic details the development, history and eventual demise of Germany’s U-1105, which represented the cutting edge of the arm’s race between subsea hunters and the hunted during WWII. Resting in the brackish waters of the Potomac River near Piney Point, Maryland, USA, the U-1105 is the most accessible sunken U-boat along the US East Coast.

by Erik Petkovic

All photos by Erik Petkovic unless otherwise noted.

In the infancy of 1942, the American shoreline was ablaze and its waters ran red with blood and black with oil. Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat) had just commenced. The mastermind of Paukenschlag, Admiral Karl Donitz, authorized five Type VII U-boats to unleash hell in American waters.

Reinhard Hardegen, commander of U-123, and his fifty-one man crew were in one of the U-boats assigned to Paukenschlag. Although unknown at the time, the world would know who he was in short order as he took aim at a tanker from 4 km/4,400 yards. U-123 hit the tanker with multiple torpedoes and sank Norness off New York. When Americans awoke to the headlines the next day, America would never be the same, and neither would the American psyche. This was the second time in five weeks (Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941) and the second time since the War of 1812 that America was attacked on its home soil.

Paukenschlag was a massive success from the Kriegsmarine perspective. From the Allied perspective, it was massively destructive. Paukenschlag was just the initial onslaught. The drum continued to beat long after Donitz’ five U-boats returned home. In the first seven months of 1942, 109 ships were lost in American waters along with 2,081 mariners.

To combat the significant loss of life and vessel, the Allies—through ingenuity and engineering—developed three keys to turning the Battle of the Atlantic. The first was High Frequency Direction Finder aka “Huff-Duff”. Although this technology was not new (as the ability to locate low frequency bearings had been used for years) the British were able to tune the technology to be able to take bearings on high frequencies when U-boats surfaced to transmit weather reports or to coordinate wolf pack attacks.

The second advancement—breaking the secret code of the German Enigma machine—was arguably the most significant. The painstaking work by Alan Turing and those at Bletchley Park not only turned the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic, but of World War Two.

The further development of ASDIC, named after the Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee, proved an effective weapon against the Grey Wolves. Known as SONAR to the Americans, ASDIC evolution was war-changing. The hunters became the hunted.

These advancements were so effective that while 109 ships were lost in American waters in the first half of 1942, zero vessels were lost in the second half of the year. As a result, U-boats were being obliterated at an alarming pace. The horrific U-boat losses caused a change in tactics: Donitz recalled the U-boats from the western Atlantic, the Kriegsmarine shifted back to lone wolf operations from wolf pack attacks, and the Allied advancements necessitated new U-boat design and engineering. Enter U-1105.

Construction

When U-1105 was launched on April 20, 1944, (Hitler’s 55th birthday) World War Two was a year from being over. The “Happy Times” had long since disappeared. The wolves were being slaughtered in high numbers. By the end of the war, the casualty rate for Kriegsmarine submariners was nearly 75%—upwards of 28,000 sailors and nearly 800 U-boats would be lost.

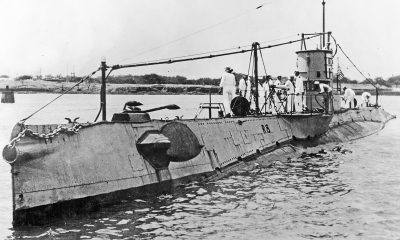

The Germans built seven varieties of Type VII U-boats. Of the 709 Type VII U-boats completed, 577 were Type VIIC, including U-1105. However, U-1105 was not a typical Type VIIC. U-1105 was a highly modified Type VIIC with the latest in German engineering.

Alberich

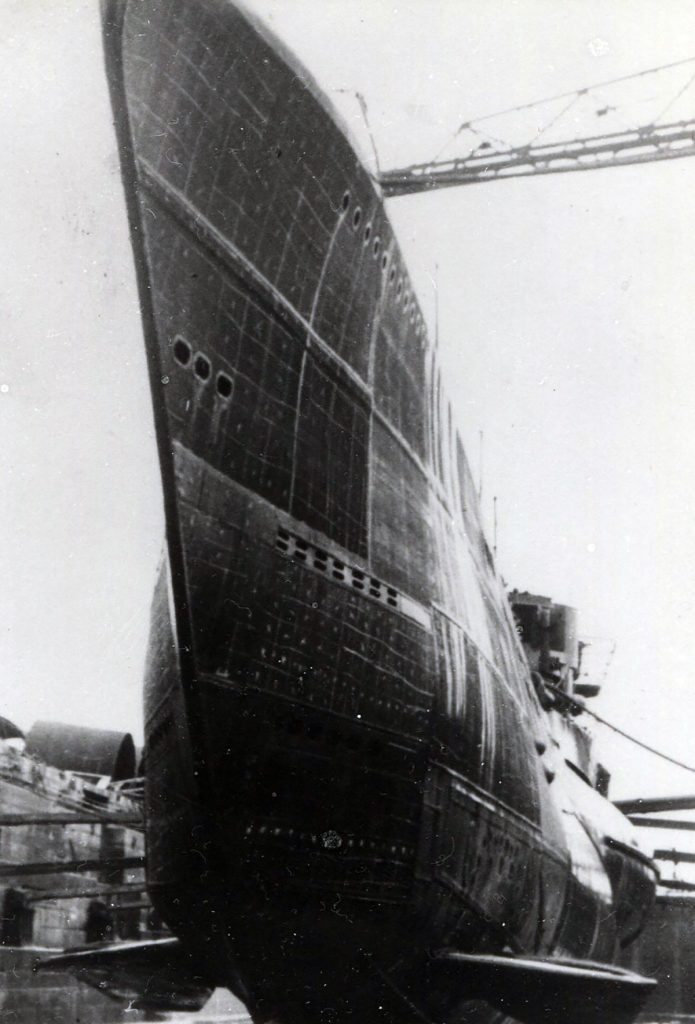

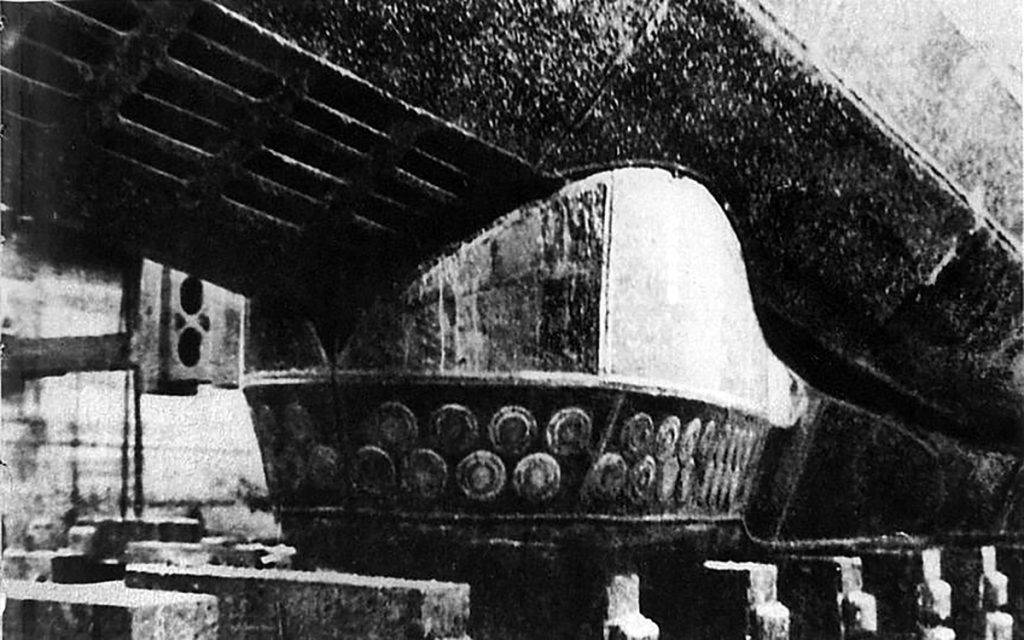

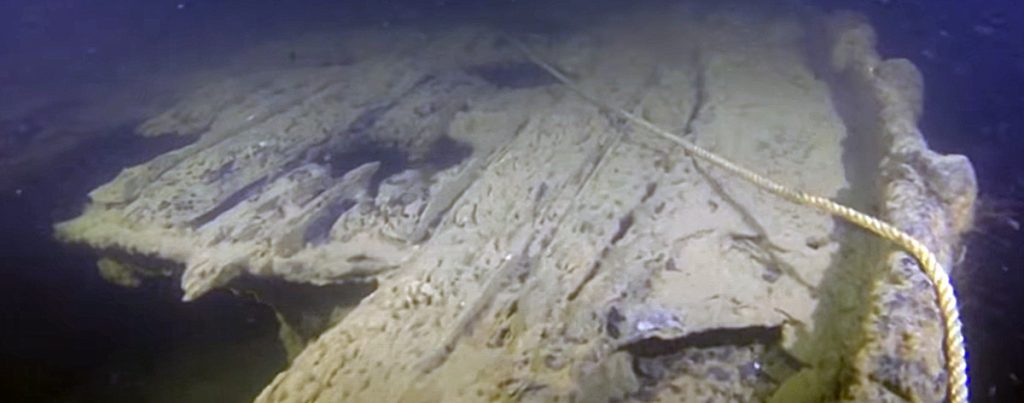

The Kriegsmarine attempted to counter the effect SONAR was having on their disappearing U-boat fleet. The Germans developed a synthetic rubber material which absorbed and dispersed sound waves—in effect, they engineered an acoustic camouflage dubbed Alberich.

An early form of stealth technology, Alberich tiles were engineered with different patterns of holes perforating the rubber which allowed the rubber to absorb the sound pinging them by SONAR from Allied ships. Similar to the tiles on the space shuttle decades in the future in which tiles were specifically engineered for a certain part of the space shuttle, specific hole patterns were engineered for specific parts of the U-boat.

Studies showed Alberich could reduce the likelihood of detection by up to sixty percent. Despite the technological and engineering innovation further enhanced by successful trials, only thirteen U-boats were outfitted with Alberich. U-1105 was one of only four U-boats outfitted with Alberich that went on a war patrol.

GHG Balkon

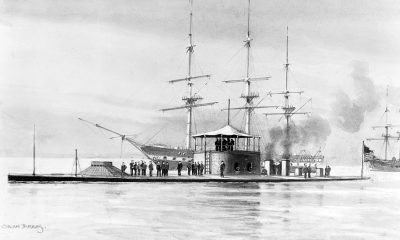

Early U-boats were outfitted with a passive sonar array called Gruppenhorchgeraete (GHG). The GHG was placed just aft of the torpedo tubes on either side of the bow containing a dozen hydrophones which helped the U-boat listen to underwater sounds and decipher Allied propellers.

Limitations with GHG lead to the development of the GHG Balkon—an advanced listening system with 48 hydrophones. The GHG Balkon increased the effective range of the U-boat’s listening capability by an astounding 70 percent. The system was so effective sounds could be heard over the horizon. U-1105 was one of nearly two dozen U-boats to be equipped with GHG Balkon.

Schnorkel

U-boats had two ways of operating – either by electric, battery powered motors or by diesel engines. U-boats could not use the diesel engines while submerged; otherwise, the engines would suck all the air in the U-boat into the engines and the crew would suffocate.. Installation of a schnorkel allowed the U-boat to operate submerged while using the diesels.

The introduction of the schnorkel was more successful than any navy would have imagined. At the beginning of the war, U-boats could stay submerged for three days. By the end of the war, schnorkel technology had been perfected to allow a U-boat to stay submerged in excess of sixty days. This remained a record until the US Navy broke it in the 1970s, but only by use of nuclear power and after decades of Cold War engineering.

Black Panther

U-1105’s conning tower emblem depicted a black panther sprawling over the world. U-1105 commanding officer, Oberleutenant zur see Hans-Joachim Schwarz explained how U-1105 received its nickname: “The name and the heraldic figure were the result of a competition in the crew. A black panther is a beast of prey in the open country. In wartime, a U-boat is also a beast of prey that attacks ships on the surface. Because the boat was covered with a black rubber coat, we thought that the name was very suitable for U-1105.”

WAR

On April 12, 1945, U-1105 ventured out in the name of the Fatherland to the western approaches of Ireland—U-1105’s hunting grounds. Careful transit of the North Sea saw U-1105 arrive west of the Outer Hebrides on April23. Schwarz surfaced briefly to send a transmission to Befehlshaber der U-boote (BdU)—U-boat headquarters. The message was short and concise: “My position is AM 0213. Weak defense and patrol.” The U-boat was so close to shore the men could see advertisements, lights, and vehicles. No one knew U-1105 was there.

On April 27, 1945, HMS Conn, HMS Redmill, and HMS Rupert, members of the Royal Navy’s 21st Escort Group, were in Irish waters carrying sonobuoys to detect U-boats. U-1105 heard the noises of the three ships. At this time, HMS Conn picked up a sonar contact which was believed to be a U-boat, but was in fact an incoming torpedo from U-1105. Fifty-seconds after firing the T5, a massive explosion rocked HMS Redmill. U-1105 remained undetected.

U-1105 attempted to descend to 100 m/330 ft to escape what was believed would be an imminent and ferocious depth charge attack. The emergency descent quickly became uncontrolled with two tons of water in her ballast tanks. U-1105 hit bottom at 570 feet. U-1105 turned off its engines and sat on the bottom. Schwarz counted 299 depth charges dropped on U-1105. After 31 hours on the bottom while avoiding detection, U-1105 surfaced.

Surrender

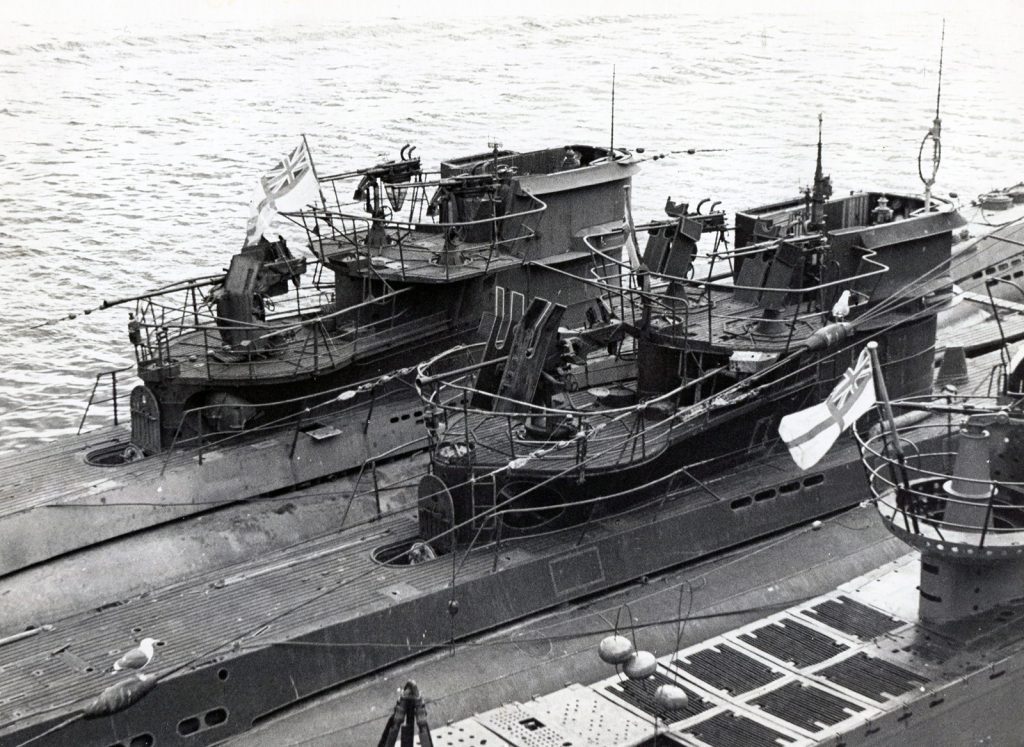

Six days later U-1105 received the order to cease all combat. World War Two was over. U-1105 surrendered at Lisahally. En route, U-1105 destroyed all classified material, communications, and paper, including her log book. All torpedoes in the tubes were discharged overboard. Additionally, all ammunition and seals for the submarine’s weapons were dumped overboard. Ironically, U-1105 surrendered to the 21st Escort Group – the same group U-1105 attacked and killed 32 of its men when it torpedoed HMS Redmill.

Testing & Evaluation

All U-boats surrendered at Lisahally, with the exception of U-1105, were destroyed per Operation Deadlight. Intelligence personnel knew from previous prisoner interrogations that Alberich existed and that the Allied forces were keen to start testing and evaluations. U-1105 was the one prize the US, British, and Soviet forces were interested in testing. The Americans were eager to get their hands on U-1105, but would have to wait until the Royal Navy completed their own trials and testing.

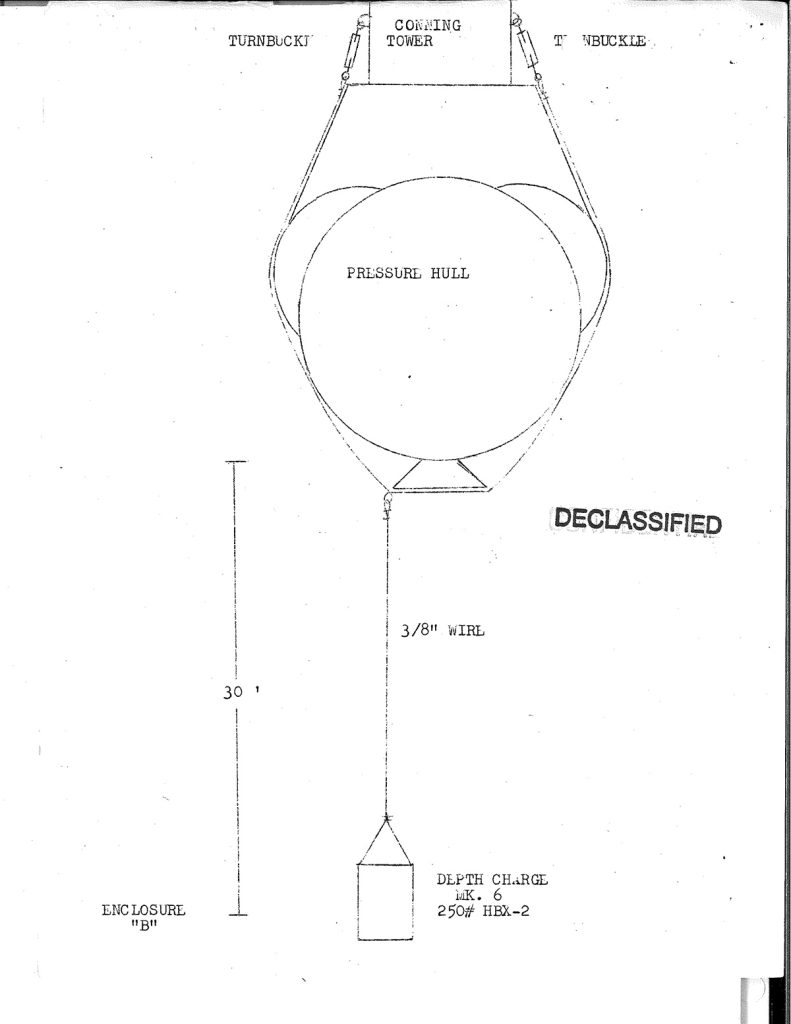

In January 1946, after a harrowing trek across the angry North Atlantic, U-1105 finally arrived in the United States and was authorized for salvage and explosives testing. At the conclusion of the proposed tests, U-1105 “shall be finally disposed of by sinking in waters of such depth as to assure a swept depth of at least fifty feet.”

Thirteen months of testing saw U-1105 sink five times. On September 19, 1948, at 1229 hours, a 113 kg/250 pound MK2 depth charge suspended 9 m/30 ft below U-1105’s conning tower was detonated. U-1105 sank in less than one minute for the sixth and final time.

Diving U-1105

U-1105 rests at a depth of 28m/91 ft in the brackish waters of the Potomac River off Piney Point, Maryland—the most accessible sunken U-boat along the US East Coast. U-1105’s bow points south toward the Chesapeake Bay. The wreck sits in an area with heavy commercial shipping traffic. Not only is the wreck easily accessible, but from April to November the wreck is easy to locate—a buoy marks the site.

The buoy is marked with several advisories including: POOR VISIBILITY, STRONG CURRENTS and US NAVY PROPERTY OBJECT REMOVAL PROHIBITED.

A small diver ball is tied directly to the top of the conning tower at a depth of 20 m/65 feet. The line is usually secured around the base of either the attack periscope or sky periscope. Free descents or hot drops are not advisable on this wreck. With the limited visibility and a seemingly ever present current, one would not be guaranteed to see the wreck if a free descent was performed. It is recommended to dive the wreck based on tide tables, with the best conditions being at or near slack high tide.

The fall and winter months allow for better visibility, less pleasure boat traffic, and fewer jellyfish. Visibility can double or triple in the winter months (2-3.5m/6-12 ft) compared to the summer months (1-1+m/3-4 ft).

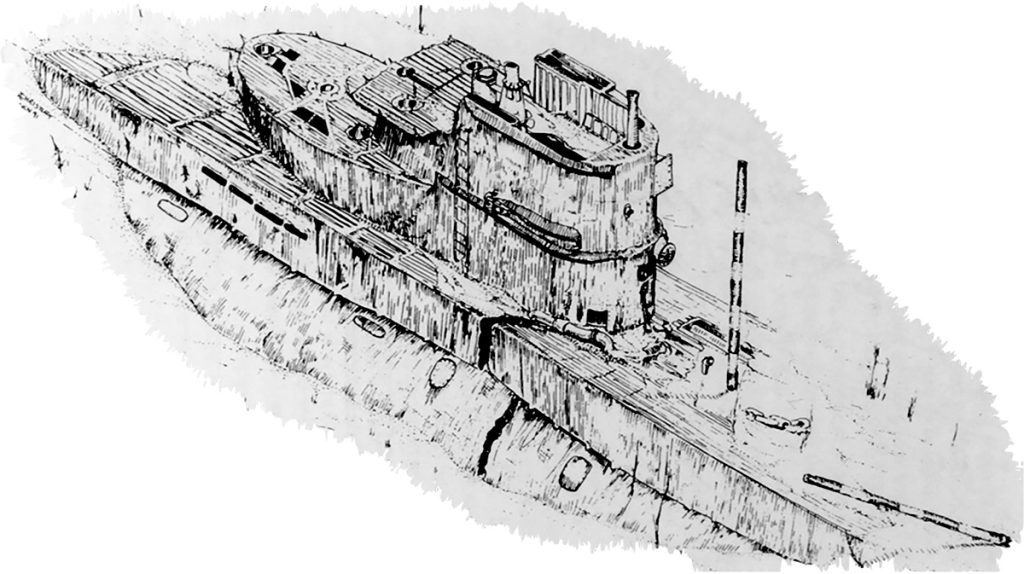

The Potomac quickly turns various hues of mundane color – greenish-brown, then brown, then shades of black. Regardless of color, it is murky. Vertical visibility is almost always better than horizontal visibility. As you approach the 18 m/60 ft mark in the black water, the faint outline of the top of the conning tower comes into view. The most prominent feature is the sky periscope housing and mount which projects above the conning tower.

Other features in the conning tower include original teakwood, attack periscope mount, diesel engine air intake, and housing for the FuMO Hohentwiel radar. The large 2 cm watertight ammunition container is located at the entrance to the upper Wintergarten. The Flak 38 gun mounts can be seen bolted to the original wood decking.

The diver will continue aft along the starboard side of the upper Wintergarten and drop onto the lower Wintergarten. Immediately to the diver’s left is the external watertight storage tube. This is where U-1105’s flags were stored. Two 3.7mm watertight ammunition containers and the M42 automatic machine gun mount can be viewed.

There are some interesting features to see while dropping down along the main deck and circumnavigating the superstructure. Below the sky periscope, flaring out from the conning tower on the right (while looking aft), is the rectangular base for the schnorkel. This is where the schnorkel would clamp into the conning tower when deployed. Along the starboard side of the conning tower is the exhaust trunking. This intricate piping is a very unique piece of maritime history, as this is one of very few sunken U-boats in the world where this can be seen.

Alberich can be seen in a multitude of places on and around the superstructure including the conning tower, both Wintergartens and saddle tanks. In 2009, the U-1105 Black Panther Historic Shipwreck Preserve was included on the inaugural list of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National System of Marine Protected Areas.

Dive Deeper

US Naval Institute: “To Hell, By Compass: The Remarkable Wreck and Rescue of USS S-5”

by Erik Petkovic

Osprey Publishing: German submarine U-1105 ‘Black Panther’ THE NAVAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF A U-BOAT

Wikipedia: German submarine U-1105

Erik Petkovic is an explorer, author, maritime historian, shipwreck researcher, and technical wreck diver. Erik is the author of multiple wreck diving and maritime history books. Erik has been featured in publications worldwide and is a consultant for various production companies. Erik regularly presents at the largest dive shows and museums and is a sought after presenter due to his unique storytelling and in-depth research. He currently lives in Southern Maryland with his wife and sons. ErikPetkovic.com