Community

Uncovering A Mass Extinction Event: The Lake Rototoa Mussel Survey

Water quality scientist Ebi Hussain led a Project Baseline citizen science team to determine what was happening to New Zealand’s Lake Rototoa mussel population. Crying cockles and mussels, alive, alive, No!! Here are the deets.

By Ebrahim (Ebi) Hussain

Header photo courtesy of Oliver Horschig.

Lake Rototoa, a cold, monomictic1 dune lake in a rural area northwest of Auckland, New Zealand, is in peril. With a maximum depth of 26m/85 ft, Rototoa is the largest and deepest of a series of sand dune lakes along the country’s western coastline. Known for its increasingly rare, diverse population of native submerged macrophytes i.e., aquatic plants, and large, freshwater mussel beds, this lake is under increasing threat from a deteriorated water quality. Although the exact cause of this deterioration is unclear, the likely culprit is a combination of factors: eutrophication, land use activities, pest invasion, and climate change.

In late 2019, the Project Baseline Aotearoa Lakes team noted signs of a freshwater mussel population collapse as well as other evidence of environmental degradation. This was alarming, as freshwater mussels are rapidly declining in New Zealand, and globally, with 70 percent of the species considered at risk or threatened.

Many people are unaware that freshwater mussels are an important part of a lake ecosystem; as biofilters and bioturbators, they filter out nutrients, algae, bacteria, and fine organic material which helps purify the water. The loss of these keystone species has likely contributed to the decline in water quality seen at Lake Rototoa.

The team’s observations prompted the design of a collaborative project between Project Baseline Aotearoa Lakes and the Auckland Council Biodiversity Team. This project is the first of its kind in New Zealand; it aims to fill critical knowledge gaps and, for the first time, quantify mussel populations in Lake Rototoa in a scientific manner.

This project is the first of its kind in New Zealand; it aims to fill critical knowledge gaps and, for the first time, quantify mussel populations in Lake Rototoa in a scientific manner.

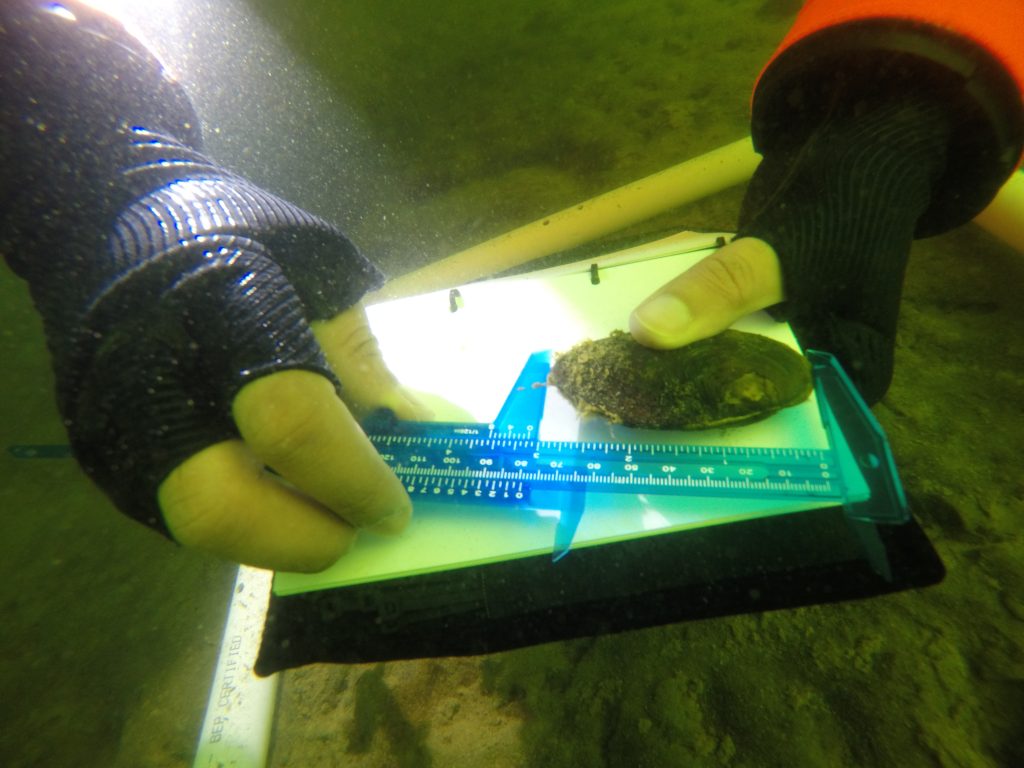

The first objective was to assess the mussel population statistics, including species composition, abundance, size class, and recruitment success. The second objective was to determine habitat preferences, bed locations, and bed limiting factors. In order to satisfy the project objectives, the team designed a bespoke survey methodology to collect all the required information in a standardized way.

Digging Into The Data

The initial series of dives focused on habitat mapping and collecting bed scale survey information. The team has mapped almost 5 km2/3.1 mi2 of lakebed and 2.2 km2/1.4 mi2 of mussel bed so far. This information provided critical insight into mussel bed formation and habitat preferences which the team used to inform the site selection for the more detailed follow up surveys.

The first phase of surveys has been completed and the results are frightening. A total of 1604 mussels (Echyridella menziesii) were counted. The combined density across all three survey sites was 41.4 mussels per m2/3.8 mussels/ft2. Out of the 1604 mussels found, 1320 (82.3%) were dead and only 284 (17.7%) were alive. The dead mussel shells were in a similar condition to the live individuals indicating that they may have all died during a recent mass extinction event.

No juveniles were seen during the surveys and all the mussels were larger than 51 mm/2 in. The surveyed population is composed entirely of mature adults, 64.1% of live mussels were larger than 70 mm/2.8 in in length, 30.6% were between 61 to 70 mm/2.4 to 2.8 in and the remaining 5.3% were in the 51 to 60 mm/2 to 2.4 in size class.

Individual dead mussels were not measured but were placed into approximate size classes, all dead mussels were larger than 51 mm/2 in with the majority of them being placed in the 61 to 70 mm and >70 mm size classes. The average age of the mussels surveyed was estimated to be between 20 and 30 years old based on their size. Some larger individuals were 80 to 100 mm long and were estimated to be around 50 years old.

This aging population and lack of younger individuals indicates limited-to-no viable recruitment in the surveyed area for more than a decade. Considering that most of the live mussels were at the upper end of their life expectancy and that there was no evidence of recent recruitment, the long-term viability of the surveyed population is low.

While the exact reasons for this population collapse are not known, recent lake surveys (fish, water quality, and macrophytes) provide some indication of possible causes. Recent fish surveys indicate a significant drop in the number of the primary intermediate host species. Both galaxiid and bully species are declining due to predation by pest fish species. Without these native fish, the mussels cannot effectively complete their life cycle.

The declining water quality of the lake is also a contributing factor. The lake’s change from an oligotrophic state, which is low in plant nutrients and high oxygen at depth, to a mesotrophic state with moderate nutrients, subjected it to increased eutrophication.

Eutrophication causes an increase in bioavailable nutrients which stimulates algal growth and in turn causes high organic silting. This silt settles on the lakebed and decomposes creating areas of low dissolved oxygen, which can cause animal die offs.

Some studies suggest that these mussels cannot survive at dissolved oxygen concentrations below 5mg/L and it is possible that the lake undergoes prolonged periods of low-dissolved oxygen during seasonal stratification. The wide scale coverage of benthic blue-green algal mats further points to periods of anoxia, or absence of oxygen, and general eutrophication.

Mussel Mania

Due to the low nutrient concentrations and the filtration capacity of the extensive mussel population, Lake Rototoa historically had good water clarity. Mussel filtration rates generally match their food ingestion rate, but once they reach their food ingestion rate, no further filtration will occur. If there is a high concentration of food (phytoplankton and zooplankton) in the water, the filtration rate is likely to be low. This means that as the lake becomes more eutrophic, the algal biomass increases, and the mussel’s filtration rate will continue to decrease.

This decrease in filtration rates will contribute to the declining visual clarity. The significant loss of mussel biomass and ultimately the loss of mussels in Lake Rototoa exacerbated the situation and may have facilitated a higher rate of eutrophication.

Sediment is also known to affect mussel populations, and there are signs of increased sedimentation; however, no clear evidence of smothering or suffocating was observed. The combination of the organic silt, sediment, and benthic algal growth can clog the mussel gills, so there are likely to be some sediment-induced population stressors.

In terms of bed extent and bed limiting factors, the team made several key observations. The mussels tended to prefer gentle slopes and did not occur in great densities on steep faced slopes/shelves. Water level, riparian vegetation extent, and wind/wave-induced disturbance appeared to dictate the upper extent. Mussel beds were generally established at a depth just below the permanent water line a short distance away from the end of the riparian edge. Fewer mussels were observed in shallow, exposed areas with visible signs of wind/wave-induced substrate disturbance.

The establishment of aquatic plants, changes in substrate, thermoclines, and potentially anoxia limited the lower bed extent. Mussels were commonly found in lower numbers in amandaphyte stands within the wider bed area and were not found at all within dense charophyte meadows. Mussels tended to establish around isolated macrophyte stands rather than in them. The lower extent of the bed mirrored the start of the deeper charophyte meadows. The littoral zone had clearly defined sections of mussels in the shallower areas (1.5 to 5 m/5 to 16 ft ) and dense macrophyte dominated areas in the deeper portion (6 to 10 m), which were relatively devoid of mussels.

In the absence of aquatic plants, the thermocline separating the warmer epilimnion above from the colder hypolimnion below appeared to dictate the lower bed extent. Almost no mussels were found past the thermocline, which was between 6 and 7 m/20 to 23 ft deep during the survey period. Since mussel bed establishment is not known to be thermally regulated, the limiting factor here may be anoxic conditions, commonly associated with hypolimnetic water. This assumption has not been validated, and a more detailed investigation of stratification profiles are planned for this upcoming year.

A clear limiting factor is the change in substrate seen past the 7 to 10 m/23 to 33 ft depth contour. The substrate changes from sand with a surficial layer of silt to a semi liquid silt/soft mud. No mussels or macrophytes were found in these areas, and the substrate does not appear to support bed establishment. Benthic algal mats covered the lower extent of some beds but did not clearly limit their establishment; since these mussels are mobile, presumably they will move if they are being smothered.

In Conclusion

Despite the concerning results, this project is a landmark event as it is the first study of its kind in New Zealand and the first detailed survey of the mussel population in Lake Rototoa. This project highlighted the pressures faced by our aquatic environments and exposed the ugly truth of what is going on below the surface. We have uncovered a mass extinction event that is currently occurring in our back yard that no one even knew was happening.

We have uncovered a mass extinction event that is currently occurring in our back yard that no one even knew was happening.

Now more than ever, projects like this are critical. Our environments are under increasing pressure, and it is up to all of us to take action to ensure that we preserve these ecosystems for future generations.

The follow-up phases of this project are planned to be carried out this summer. The data we have collected thus far has enabled the Auckland Council to make informed decisions on how best to manage these threatened species and preserve native biodiversity. We hope that our continued efforts at this lake will contribute to preserving this ecosystem and prevent the complete extinction of these threatened species.

Footnotes:

- Cold monomictic lakes are lakes that are covered by ice throughout much of the year. During their brief “summer”, the surface waters remain at or below 4°C. The ice prevents these lakes from mixing in winter. During summer, these lakes lack significant thermal stratification, and they mix thoroughly from top to bottom. These lakes are typical of cold-climate regions.

Dive Deeper:

InDepth V 1.6: Bringing Citizen Science To Lake Pupuke by Ebrahim Hussain

Learn more about Project Baseline

View their online database

Get involved

Ebrahim (Ebi) Hussain is a water quality scientist who grew up in South Africa. As far back as he can remember he has always wanted to scuba dive and explore the underwater world. He began diving when he was 12 years old and he has never looked back. Diving opened up a new world for him and he quickly developed a passion for aquatic ecosystems and how they work. The complexity of all the abiotic and biotic interactions fascinates him and has inspired Ebi to pursue a career in this field.

He studied aquatic ecotoxicology and zoology at university, and it was clear that Ebi wanted to spend his life studying these subsurface ecosystems and the anthropogenic stressors that impact them. After traveling to New Zealand, Ebi decided to move to this amazing country. The natural beauty drew him in, and even though there were signs of environmental degradation, there was still hope. Ebi founded Project Baseline Aotearoa Lakes with the goal of contributing to preserving and enhancing this natural beauty as well as encouraging others to get involved in actively monitoring their natural surroundings.