Cave

Under the Taurus Mountains: The Karstdive Discovery

The following article originally appeared in the February 1996 issue of Atlas Travel Magazine but has been adapted and updated. You can watch the original documentary on the KarstDive project as well on InDepth.

By Dr. Todd R. Kincaid

Over 20 years ago, two cave divers made history when they discovered Asia’s largest cave in Turkey. Global Underwater Explorers’ (GUE) “founding fathers,” Jarrod Jablonski and Todd Kincaid, Ph.D., set out on the Project Karstdive cave exploration in the Taurus Mountains in the summer of 1995. The goal was to explore, map, and document several underwater cave systems along the southern flank of the Taurus Mountains. The following is Kincaid’s account of the exploration.

Squashed in the back seat of the 4WD, I looked out the window toward the rugged mountains in the distance with amazement. I had suddenly realized that Jarrod and I, a couple of cave-diving college boys from Florida, were in Turkey, 10,000 km from home, about to suit up and dive under a mountain. The people here considered us the experts, the expert explorers who would fathom the depths of their fabled and mysterious submerged system of caves, produce accurate maps, and capture it all on videotape. A lump as big as the mountain lodged in my throat. Would these caves even go past the light zone? How deep? How far? How much water, and how clear?

We soon would find answers to these questions and more.

We arrived at Suluin for the first dive on August 19 around 9:30 a.m. Since the cave was reported to run deep near the entrance, we had mixed 15/50 trimix (15% oxygen, 50% helium, balance nitrogen) in the back tanks with an air stage bottle and 50% nitrox and O2 for decompression. As the water rose over my head, I turned away from the sunlit entrance to see the floor slope away beneath me. The cave appeared cobalt blue, a manifestation of our lights reflecting off the white walls through the limpid water. Gökhan and Zafer, our teammates, were snapping photos like mad. Jarrod was tying off his reel to the end of another thick line that only penetrated the cave some few tens of meters. The cave walls were blanketed with flowstone, and a stalagmite forest hung overhead.

Jarrod and I pushed down and into Suluin while Gökhan and Zafer stayed in the shallows to measure and photograph the cavern. We followed it back to a passage that led in about 200 m and down to over 60 m deep before it apparently came to an end. We faced a small restriction in the floor, which prevented us from advancing any further; our equipment made us too bulky to be able to pass through. Returning to the main cavern we followed another passage for around 50 m when it too came to an abrupt conclusion, leading up to a surface above. We would later find this air chamber from decompression, but surfacing there revealed only more flowstone and no way out. It looked as if no further tunnel was going to be found, and we headed back to the entrance.

Reaching the surface didn’t brighten the mood either, as our friends had more bad news. The Jandarma (Turkish National Guard) had come while we were submerged. Apparently, the Kirkgöz region is a protected archeological site and special government permission is required to be there. Once again, we were faced with more delays. Two days passed before the necessary permits were obtained and diving could resume.

We returned to Suluin on August 23rd. Though morale was extremely low, we needed to complete the cave survey and shoot some more video. Once more, the gear was donned and the four of us descended. Gökhan and Zafer shot video of the cavern and took more photos while Jarrod and I swam in to finish collecting the survey data. Little did we know, the tide was about to change. We headed for the deep tunnel first. At line’s end, Jarrod was investigating a small fissure while I dropped down to investigate the restriction.

Squeezing down to 65 m revealed a small tunnel that ran back and further in. Before I could come up, Jarrod entered it with the reel, letting out the nylon as he went. We followed the small passage as it snaked circuitously down to a depth of over 80 m. The passage then began to rise, and before I knew it we were traversing what seemed like a large hallway at only 45 m. Turning a corner, our limestone hallway widened, exploding into an enormous room. Unfortunately, in our pessimism, we had left the scooters back at Kepez not expecting to find any leads (it always seems to work like that, probably thanks to a guy named Murphy). I checked my gas pressure to find that it was time to return. Begrudgingly, I signaled Jarrod and we headed out. At decompression, we made plans for the next dive. As I remember, it was captured in a single word: scooters! That dive set the stage for the rest of the trip.

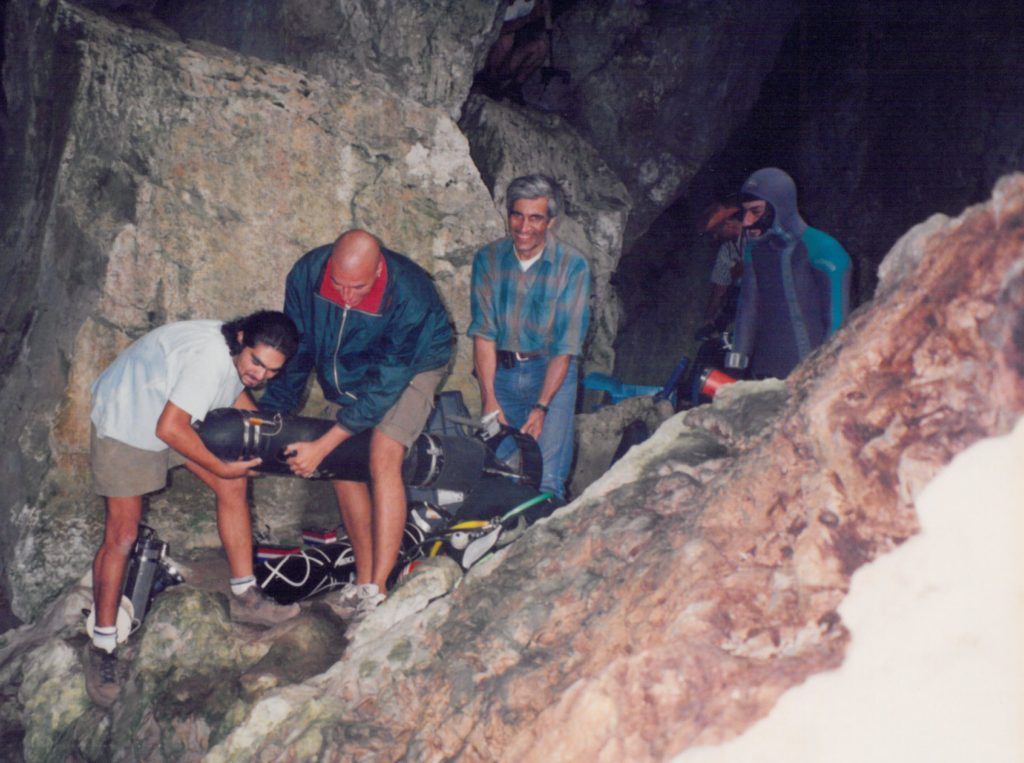

Though most of the equipment was left in the cave for the duration of our exploratory efforts in Suluin, trimix and nitrox bottles needed to be remixed, O2 refilled, and scooters and light batteries required charging for each dive. This became our routine for every diving day. Each morning, the task of hauling tanks, scooters, and light batteries uphill to the cave was shared between five of us: Jarrod, Gökhan, Zafer, Hakan (our team doctor), and me. After the dive, Gökhan, Zafer, and Hakan were left to haul it out themselves, as the risk of decompression sickness left Jarrod and I unavailable. Upon arriving back at Kepez, the tanks were remixed and filled, the batteries put on charge, and decompression tables run. The day usually ended around 9:00 p.m., just in time for a quick dinner before diving into slumber.

We spent two more days exploring Kirkgöz-Suluin. We discovered the Stadium on the next dive, the largest water-filled room I have ever encountered. Flowstone, travertine draperies, and stalagmites covered the walls—that is, the walls we could see. One whole dive—over 40 minutes in the Stadium—was spent following three walls of the same room. We couldn’t explore the top of the rooms without violating the decompression ceiling. The bottom was more than 20 m below. I felt like a fly on a window looking for a way out. So many leads fanned out before us that one year of diving could be spent trying to count them all.

On August 25th we descended into Kirkgöz-Suluin for the last time. We explored and surveyed several side tunnels leading away from the Stadium and brought a video camera and video lights to document our finds. All total, Suluin revealed over 800 m of passages, a room the size of a football stadium, and a wealth of archeological artifacts. Satisfied with a job well done, we carried the equipment down the mountain one final time and headed back to Kepez. We had only two more days to hit the last two targets before our equipment would have to be packed for the return trip to the USA.

The next stop was Düdenbasi, a large spring discharging from the travertine plateau just outside of Antalya. It was familiar territory. The setting was reminiscent of our Florida encounters: a large magnitude spring discharging from a lat carbonate plateau. The spring and the surrounding area have been converted into a state park where tourists come from all over the world to see the lush oasis in the otherwise arid Turkish landscape. From a diverted stream channel, water falls over travertine cliffs to mix with the water from Düdenbasi below. The height of the waterfall, the blue water at the bottom, and lush green trees and grasses combine to create a spectacular setting for a dive.

Sadly, attention was quickly diverted from the wondrous natural beauty to the piles of litter on the shores and the knowledge that though the water quality was still good, the current practice of sewage disposal directly to the travertine plateau without treatment would inevitably have its effects. It’s unfortunate that such a beautiful place should be subjected to the litter of tourists and the environmental catastrophes created by man. Expeditions such as this one will hopefully raise the public awareness and help foster a concern for conservation and environmental protection in the Antalya region.

Holding true to the apparent “Turkish Tradition,” Düdenbasi came up with a surprise. After penetrating 400 m, the tunnel had dropped to a depth of over 65 m, and lacking the necessary decompression gas for a dive this deep, we were forced to turn back. Though another dive was certainly in order, our timetable couldn’t permit it, and we had to say goodbye to this mysterious tunnel at Düdenbasi, at least for 1995.

We spent another late night mixing gas, filling tanks, charging lights and scooters, this time loading it all into a minibus. The following morning’s four-hour drive would take us to our last target, Gök Cave, a reportedly deep cave somewhere near the town of Finike on the Mediterranean coast. Luckily, the bus came with a driver—most of its passengers were dead on their feet. Gokhan’s wife, Elvan, had come down from Ankara to join us, but she probably found better conversation with the driver on that trip.

We arrived in Finike around 11:00 a.m. on August 27th. A French report on the cave that had been prepared some years before provided us with the only directions. It felt like our luck had changed when we quickly found the cave just beside the highway, only 1.5 km south of Finike. That feeling quickly disappeared, however, when we found that getting to the water required a 30-m hike up the mountainside, followed by the same distance down a treacherous scree slope into the entrance of the cave. The slope was also covered in goat dung, which was not only distasteful but also quite slippery.

A beautiful blue pool sat at the base of an immense cavern in the side of the karstified limestone mountain. Long strands of green algae floated calmly on the surface. The water was colder than Kirkgöz and Düdenbasi, and was quite salty. Since Gök Cave was thought to be deep, we came prepared with 15/50 trimix in both the back tanks and in a single stage bottle each. Air, 50% nitrox, and O2 were brought in for decompression. After all the equipment had been brought in and set up, decompression tables were run to cover any imaginable contingency. We had been diving for the last four days straight and wanted to play it safe. In 5-minute intervals from 3 to 55 minutes, tables were cut on a laptop computer and transferred onto an underwater slate for 7-m depth intervals from 60 to 100 m. It took over an hour and everyone’s patience wore thin. But we were prepared (at least I thought we were) for anything Gök Cave had to offer.

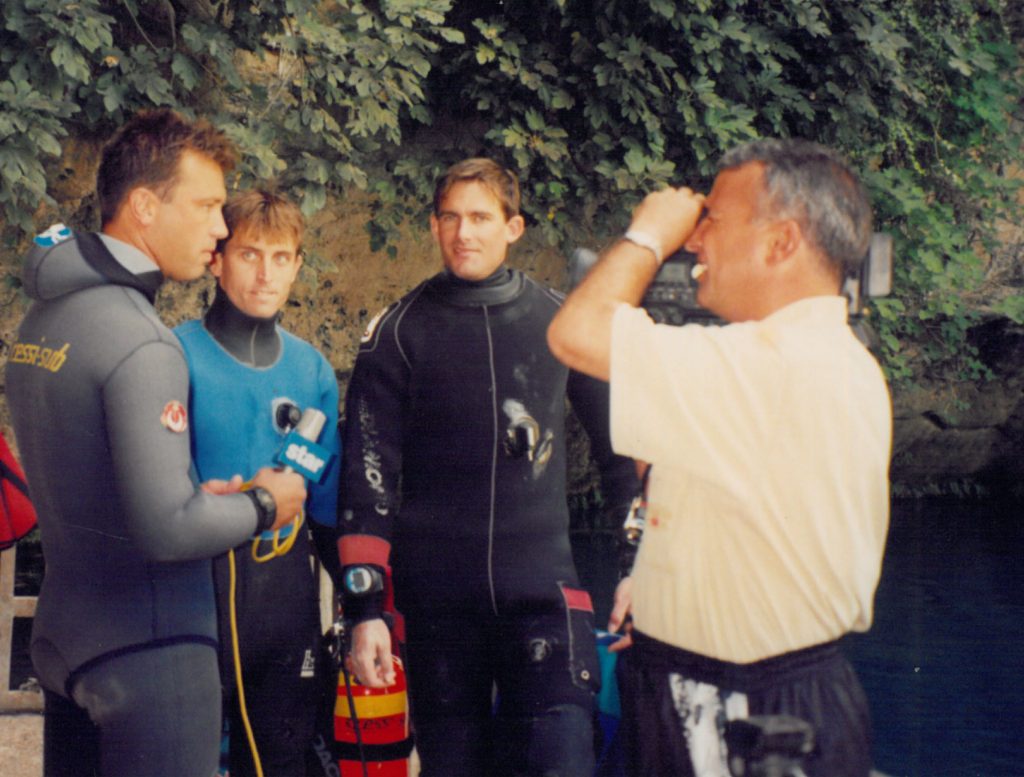

After gearing up, Jarrod and I descended into the cavern to decide whether video would be in order. I was immediately overwhelmed by the size of the entrance. Later it was measured to be over 80 m in diameter. The water was “air” clear, and the cave immediately dropped deep out of sight, heading deep into the mountain without diminishing. After dropping scooters and decompression bottles, we returned to the surface for Gökhan and Zafer, the video camera, and every light we had. Trying to stay above 30 m, the four of us slowly swam around the cavern entrance videotaping massive speleothems on the walls and ceiling, and the spectacular view of the sun filtering into the gargantuan mouth of the cave.

After 15 minutes it was time to split up. The camera and lights were handed off to Gökhan, and Zafer, Jarrod, and I headed down. Even though the water was crystal clear, we couldn’t simultaneously see both sides of the tunnel due mainly to its sheer size. Being in the middle brought a disturbing feeling of insignificance. Jarrod picked the left wall and we continued to follow the ceiling, which ran at a slight but noticeable angle that took us continually deeper. While Jarrod spooled out the line, I made the wraps around stalactites so huge that it was like giving them a bear-hug to get the line around. Finally, we came to a ledge on top of a huge snow-white wall. At 90 m below the surface, the ledge provided a necessary depot for our scooters, as they aren’t designed for that kind of depth. Making another wrap, I followed Jarrod in his descent along the face of the wall where the conduit kept going in and down.

Looking at my depth gauge, I realized that Gök Cave had also held true to the “Turkish Tradition,” as we were passing 110 m and still dropping. We finally tied off the reel on top of a huge fallen boulder at 117 m. The cave appeared to bottom out. A small restriction looked enticing but, being 20 m deeper than our deepest decompression schedule, we had no time to think about anything but getting out. Returning to the scooters at 90 m, a loud popping sound was a sure sign of trouble. Jarrod’s scooter had imploded from the excessive pressure! Using the motor to keep it up, Jarrod swam it out while I finished collecting the survey data. Unfortunately, I was too busy with the survey to see for myself, but Jarrod said that he could see the sunlit entrance all the way out from the 80 m depth.

Three and a half hours later, we broke the surface of the water a little apprehensive about decompression sickness but still overwhelmingly excited at having explored such a tremendous cave. We had penetrated over 230 m of Gök Cave to a depth of 117 m, with a total bottom time of 25 minutes, excluding the 15-minute video dive. As it turns out, Gök Cave is now the deepest known underwater cave in Asia. The expedition couldn’t have ended in a better way.

Karstdive 95 was a joint research and exploration project conducted by the WKPP and SAD in cooperation with the International Research and Application Center for Karst Water Resources (UKAM) of Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey, the University of Wyoming Department of Geology and Geophysics (UWG&G) of Wyoming, USA, the State Hydraulic Works (DSI) of Antalya, Turkey, and Kepez Electric Company, also of Antalya.

Dr. Kincaid has been diving since 1979 and cave diving since 1987. He has explored and mapped underwater caves in Florida, Turkey, Mexico, and China and studied the role of caves in controlling groundwater flow patterns for M.S. and Ph.D. university degrees. He is currently working with a team of researchers and explorers with the Florida Geological Survey and GUE’s Woodville Karst Plain Project to understand karstic groundwater flow to Wakulla Spring in North Florida. That work has included detailed underwater cave mapping, quantitative groundwater tracing, hydraulic metering of discrete cave passages, and the numerical simulation of conduit/matrix groundwater flow. He is one of the original founders of GUE, and also leads a small consulting company, GeoHydros, which specializes in geological and groundwater modeling. He also serves on the Advisory Board for the Hydrogeology Consortium and the Florida Springs Institute, both nonprofit organizations dedicated to the protection of Florida’s springs.