Latest Features

Understanding Oxygen Toxicity Part II: Hypotheses and Hyperoxia

Diver Alert Network’s Reilly Fogarty examines the latest research on the mechanisms behind CNS and pulmonary oxygen toxicity to tease out what we think we know and what it means for your diving. Watch those PO2s!

by Reilly Fogarty

Header photo by Stephen Frink, Research conducted at the US Navy Experimental Diving Unit.

You can read Part I of this series here.

The history of oxygen toxicity research serves well to set the stage for the complication and nuance of modern research, but it’s important to recognize that what we are currently working with is a series of compounded hypotheses on the effects of oxygen in the body. They’ve been tested to varying degrees and serve as the basis for compounding theories and practices both medical and academic in nature, but the more we learn about the function of oxygen in the human body, the more we realize what we don’t yet know. The specificity of the mechanisms combined with the concurrent reactions required to make those mechanisms possible fills the pages of more than one textbook, but here’s a real-world look at what we think we know, and what it means for divers.

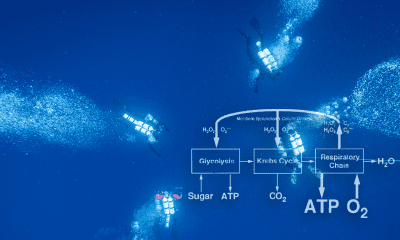

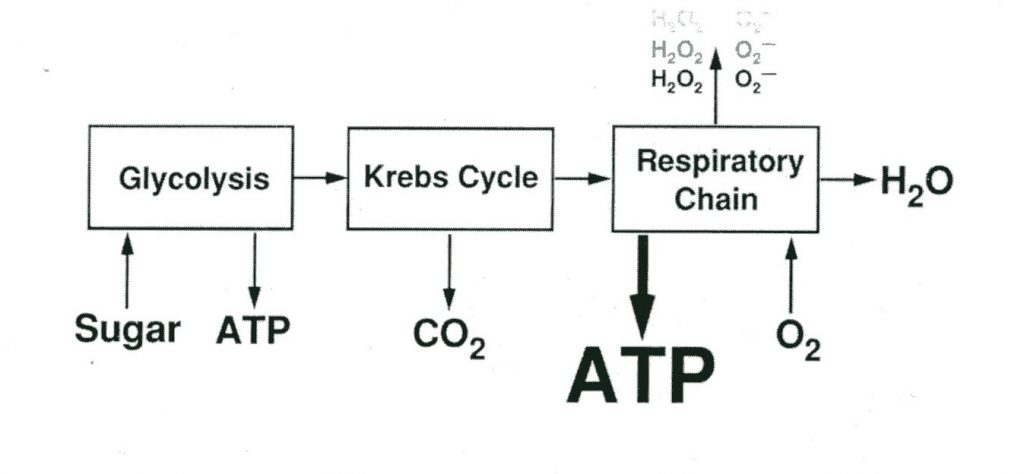

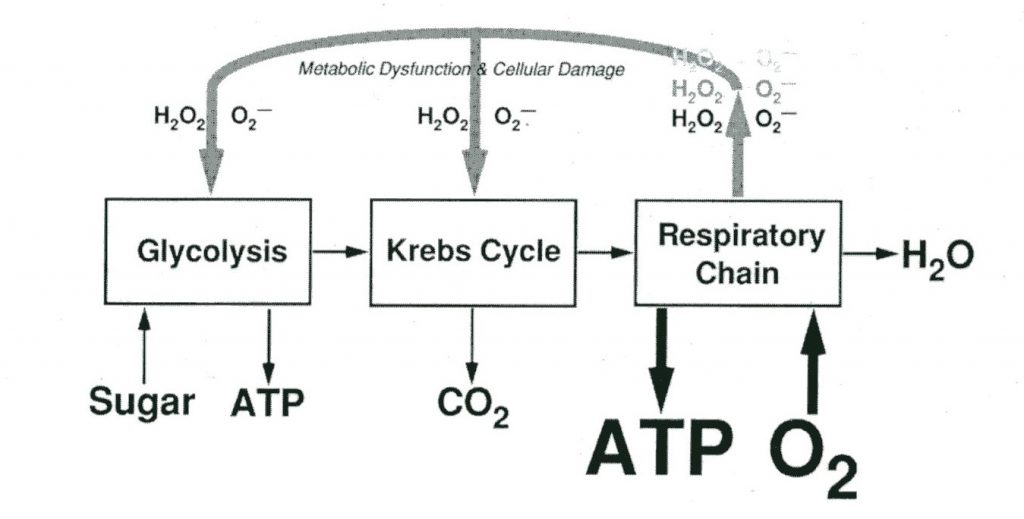

Starting Small

Most modern theories of oxygen toxicity focus primarily on the function of oxygen free radicals and lipid peroxidation, in a mechanism that mimics inflammatory processes in the body. Oxygen free radicals, or reactive oxygen species (ROS) are ions (atoms or molecules having an unpaired electron in an outer orbital) that are highly reactive. The pairing or loss of the lone electron results in the generation of an additional free radical, leading to a continuous chain of species production. Their initial creation is primarily the result of an oxi-reductive process in the electron transport chain, the result of which is superoxide, hydrogen peroxides, hydroxyl, and water (Chawla, 2001). These free radicals result in lipid peroxidations (a type of oxidative lipid degradation) in cell membranes, damage to cellular enzymes and interference with nucleic acid and protein synthesis. Exposure to high partial pressures of oxygen increase free radical production and may result in damage to the pulmonary epithelium, intra-alveolar edema, interstitial thickening and several other conditions (Cooper, 2019).

Diagram courtesy of aquaCORPS.

The general mechanism for central nervous system (CNS) toxicity resulting in tonic-clonic seizures (convulsions involving both muscle stiffening and twitching or jerking) involves hyperoxia-induced free radical production overwhelming specific neural pathways, combined with localized neuron depolarization and hyperexcitability. This theory suggests that exposure to high partial pressures of oxygen results in an increase in the firing rate of specific neurons, notably those of a part of the brain called the caudal Solitary Complex (cSC), a portion of the dorsal medulla oblongata which is important in cardiorespiratory control and has some neurons that are particularly sensitive to hyperoxia and pro-oxidants (Ciarlone, 2019). The effect of this hypersensitivity combined with increased free radical production is theorized to be the stimulus for the seizure evolution seen in CNS oxygen toxicity, although other mechanisms bring epilepsy models into the fold and propose looping and self-amplifying circuits of neurons that result in seizure evolution. An additional mechanism proposes seizure onset as a result of hyperoxia induced enzyme inhibition, notably of Gama Amino Butyric Acid (GABA). GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter, and inhibition of its production is theorized to result in neuronal excitation resulting in seizure (Treiman, 2001). These mechanisms are not exclusionary and in some instances may combine, overlap or catalyze each other.

Pulmonary oxygen toxicity is typically proposed to follow a similar inflammatory mechanism caused by free radical production and lipid peroxidation. These mechanisms involve redox and inflammatory damage throughout the body, primarily to the capillary endothelium and alveolar epithelium resulting in impaired gas exchange and neutrophil infiltration leading to respiratory failure (Ciarlone, 2019). The visible effect of this inflammatory reaction is the irritation of the airway, decreased gas exchange and eventual thickening of alveoli and damage to the alveoli and airway tissues.

There are several additional and notable mechanisms for both CNS and pulmonary toxicity that involve other sources of free radical damage catalyzing neural misfiring, damage to proteins and resulting immune responses, and inappropriate oxidative signals as a result of exposure to hyperbaric oxygen — what’s important to understand in this is not the specifics of the proposed models as much as the applied cause and effect. Exactly why each of these mechanisms functions as it does remains unclear in some instances, but the proposed hypotheses bring us closer to understanding what inputs can be altered to understand and eventually address the resulting symptoms of oxygen toxicity. What’s interesting to note is the significant overlap in many of the proposed mechanisms, many of which provide reactants for or accelerate other similar mechanisms, as well as the recent convergence of many theories on the concept of oxygen toxicities effects being inflammatory or autoimmune in nature.

Day-to-Day Variability

The single most significant issue in applying what we know about oxygen toxicity isn’t the unknown nature of specific mechanisms, but the huge variability in the exposures that result in symptom evolution, even in the same individual on two separate days. This variability is partially a function of the many contributing factors in oxygen toxicity, resulting from differences in factors that contribute to, inhibit, or result in the catalysts involved in the mechanisms discussed above. The majority of this variability is proposed to be the result of both the multitude of pathways that result in injury, and factors like antioxidant defense levels, neurotransmitter levels, genetic factors, nitric oxide production rates, and hormone levels — particularly concerning thyroid function, epinephrine production and ACTH levels (Shykoff, 2019).

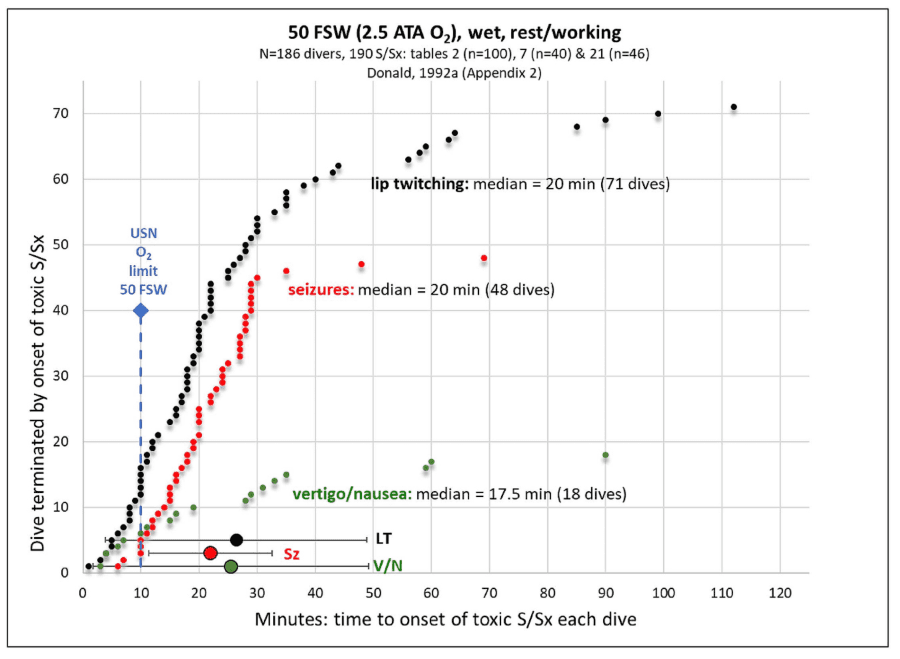

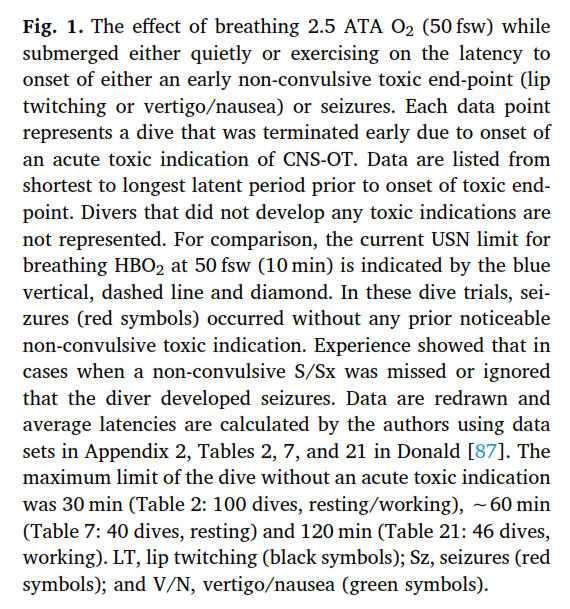

This variability is so great that some models propose that CNS toxicity can be affected by inert gases, visual input, and circadian rhythm (Mathieu, 2006). The result of all of this is that the list of variables that contribute to oxygen toxicity risk of all kinds is both incomplete, and so long and variable that they cannot possibly be controlled for in their entirety. In the real world this means that we must apply enormous levels of conservatism to what amounts to an educated guess at the average limits of divers. Comparison of models created by military researchers (using exceptionally fit young males performing difficult work underwater as a model), and academic models (using samples that more closely resemble the diving population) result in significant variability both by model and by acceptable risk.

For the most part we, as an industry, have found some success in settling for the current NOAA oxygen exposure guidelines, but even these see unexpected injuries in use. The management of some primary diving-related risk factors for oxygen toxicity has resulted in the ability of some divers to far exceed recommended guidelines seemingly without symptoms, but because of this variability we are largely unable to quantify the risk they face — it’s as of yet unclear if the diver performing hours long decompressions in a habitat is taking a gamble with each dive or maintaining a moderate safety margin with the controls they’ve put in place.

Carbon Dioxide

Carbon dioxide may be the greatest controllable risk factor in CNS oxygen toxicity, and unmitigated CO2 production and retention has been correlated with significantly increased seizure risk. This risk is primarily the result of the combination of CO2 production from exercise, combined with increased retention as a result of increased gas density, hydrostatic compression of the lungs, and dead space ventilation caused by the length of tubing in a breathing apparatus (Carlione, 2019). While breathing a hyperoxic gas may initially inhibit ventilation, continued exposure stimulates ventilation and decreases CO2 retention as long as that CO2 is effectively eliminated. The result of this is increased CO2 production and retention to increase arterial PCO2 and the production of respiratory acidosis. This is exacerbated by the oxygen induced interference with CO2 transport in the body, resulting in a higher dissolved PCO2 and decreased bicarbonate and carbamino concentrations (Carlione, 2019).

The resulting hypercapnic acidosis increases free radical species formation via a cascade of mechanisms involving an increase in hyperoxic blood delivery to the brain, and an interaction called the Fenton Reaction that in combination results in increased free radical production, which accelerates oxidative stress and increases seizure risk. Like the mechanisms above, this is a broadly accepted but still unproved hypothesis that results in an increase in seizure risk, but while the specifics of the interaction may be variable, the effect of CO2 on convulsion risk have been strongly correlated.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia presents as a risk factor of its own, and one that compounds the effects of CO2. The specifics of this mechanism remain unclear but the reduction in peripheral blood blow, increased cardiac output and redistribution of blood volume to the core results in increased oxygen delivery to the CNS, which may compound issues with both with CO2 retention and delivery of hyperoxic blood to the brain (Mathieu, 2006). Other factors like circadian rhythm, sleep, inert gases, diet, and gender have been similarly correlated with decreased seizure latency (the time between stimulus and seizure onset), but with varying degrees of study and theorized modeling.

The real-world takeaway is that we know a little about a lot of proposed mechanisms, and a lot about very few facets of oxygen toxicity. There’s a growing convergence of theories around the idea of an inflammatory or immune response being central to the mechanisms for both CNS and pulmonary oxygen toxicity, and while these theories are quite good and have withstood significant testing, many have yet to be definitively proven. Academically the outlook is both more obscure and more hopeful — this article is just a brief summary of some of the more common models of oxygen toxicity, but there are numerous other contributory and more detailed models and mechanisms currently being researched to explain the effects of high partial pressures of oxygen on the human body.

It’s worth noting that as divers we are primarily concerned with just CNS and pulmonary toxicity, but the effects of oxygen in the body are far more reaching and involve numerous other physiological changes. The future of research into the topic yields promise both on academic and applied fronts. Trials with inhibitors of some free radicals, anti-adrenergic and anti-epileptic drugs, ketone metabolic therapy and hyperbaric preconditioning have shown significant promise in the reduction of oxygen toxicity effects.

Ongoing research into human exposure limits promises to improve our ability to plan real-world dives and extend out limits, and a broad field of researchers are working to overcome the gaps in knowledge that we currently have. There may not be a unique revelation in the currently published research that changes the way that you plan your dives, but the simultaneous progress on so many facets of our understanding indicates that are likely on the cusp of a new understanding of how to manage oxygen exposures and keep ourselves safe in the water.

Thank you to Dr. Andy Pitkin, Dr. Barbara Shykoff, and Dr. Neal Pollock for their willingness to share their expertise in their respective fields.

Dive Deeper

For more information on the specific mechanisms of oxygen toxicity and the ongoing clinical trials mentioned in this article, please visit the references linked below.

- Chawla, A., & Lavania, A. K. (2001). OXYGEN TOXICITY. Medical journal, Armed Forces India, 57(2), 131–133. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(01)80133-7

- Cooper JS, Shah N. Oxygen Toxicity. [Updated 2019 Mar 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-.

- Ciarlone, G. E., Hinojo, C. M., Stavitzski, N. M., & Dean, J. B. (2019, March 9). CNS function and dysfunction during exposure to hyperbaric oxygen in operational and clinical settings.

- Treiman, D. M. (2001, December 20). GABAergic Mechanisms in Epilepsy.

- Shykoff, B. (2019). Oxygen Toxicity: Existing models, existing data. Presented during EUBS 2019 proceedings.

- Mathieu, D. (2006). Handbook on Hyperbaric Medicine. Dordrecht: Springer.

Reilly Fogarty is a team leader for risk mitigation initiatives at Divers Alert Network (DAN). When not working on safety programs for DAN, he can be found running technical charters and teaching rebreather diving in Gloucester, MA. Reilly is a USCG licensed captain whose professional background includes surgical and wilderness emergency medicine as well as dive shop management.