Education

Urination Management Considerations for Women Technical Divers

Tech diver and doctoral student, Payal Razdan, offers an in-depth review of the options available to women tech divers for handling the call of nature.

By Payal S. Razdan

Header image by Rich Denmark

Proper hydration is an important element in the health and safety of athletes and sports enthusiasts. The ability to eliminate these fluids is equally essential in maintaining fluid balance and physical comfort. Appropriate physical protection is critical when diving for extended periods of time, both in colder temperatures and contaminated water. There are also times when professional and safety divers must remain suited when providing surface support. Drysuits offer the protection needed but require additional accessories in order to make it possible to stay in the suit for prolonged periods.

Traditionally, external urine collection systems (eg, adult diapers/nappies and external catheter systems) are used in settings when stopping or removing protective gear is not optimal. Understanding some of the anatomical and technical considerations needed to take care of this most basic physiological function may help divers select the right device for them and manage any potential complications that may arise.

Early Urine Management

What we now call ‘standard diving dress’ first evolved from ‘closed-dress’ (diver completely enclosed in helmet and flexible dress with hands exposed) during the 1830s. In the early 1840s, while working on the wreck of the Royal George off Portsmouth in Southern England, Augustus Siebe made gear modifications to meet divers’ needs and suggestions. This work eventually led to ‘standard-dress,’ but an option for external catheter systems did not follow until some 40 years later. In the 1930s, commercial diving systems initially held the urine in a catchment bag connected to a one-way overboard discharge valve that was opened once on the surface. Modernization eventually made it possible to void while immersed. These systems were incorporated into technical diving around the mid-90s, but were still designed exclusively for use by men.

According to Peter Dick, editor of the International Journal of Diving History, while some women were diving during the 19th century, it was not until the early 1930s that females began coming into the sport, some by way of diving their own homemade gear. It was not until after World War II that women began to take to sports diving in larger numbers. Equipment modifications eventually evolved to include women’s needs, albeit slowly. A female-friendly version of an external urine collection device was not available until the early 2000s. Until this point, women had been limited to either holding, self-catheterization, or nappies (adult diapers). For women divers, there are various types of external urine collection devices: portable urinals, female urination devices (FUD), nappies, and the external catheter systems; however, the latter two appear to predominate.

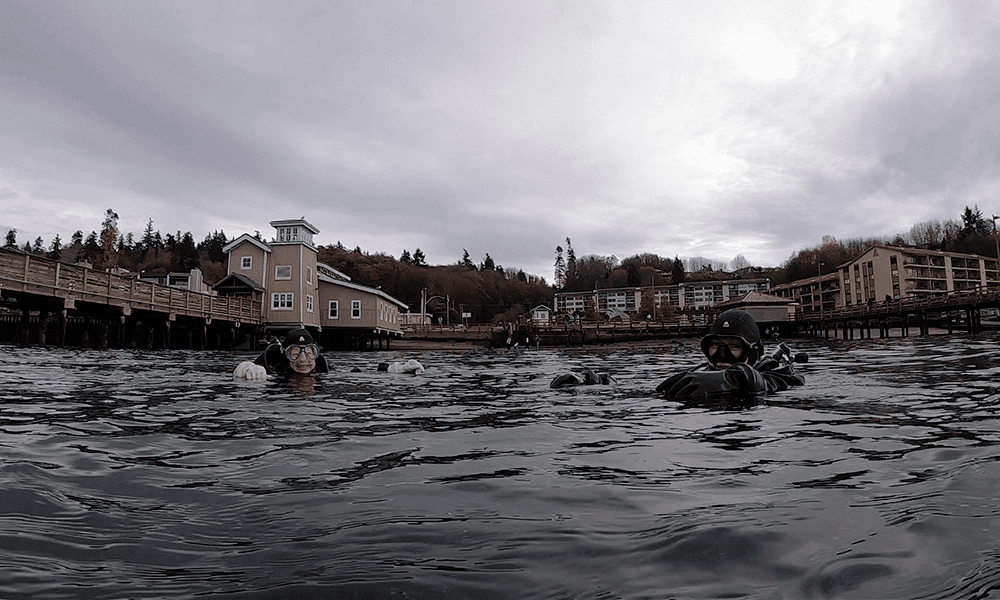

Divers preparing to go under the ice at Thetford Mines, Quebec. Shows that there is nowhere to go privately. Photo by Payal Razdan.

Nappy Know-How

Nappies were the original go-to device and remain commonplace in diving. Although they seem to be underappreciated, they are easy to don. While divers may choose to rely on store-bought brands there is an incredible, almost overwhelming, variety available online.

Nappy selection can be a science. Different brands allow for varying usable capacities up to an astounding 95 oz (2.8 L) with the Dry 24/7 Max AbsorbencyTM1. “While nappies may be preferred for shorter dives, it is about the right tool for the job” said Beatrice Rivoria, marine biologist and technical instructor with Zero Emissions who prefers nappies for short dives. Contrary to what some divers might believe, brands with max absorbency could be used for extended dive times. Additional features to consider are the wet thickness (how thick the product becomes at usable capacity), wicking distance, cost per brief, dimensions, and accessibility. Like with any diving equipment, it is best to try different options when possible. Some manufacturers and retailers are willing to send samples.

Nappies are available as either pull-on underwear style or tabbed briefs, the latter allowing you to slip out of and into a fresh nappy without the need to completely disrobe. This can be useful for instructors doing multiple dives per day, for individuals surrounded by ice and snow, for divers with no access to restrooms, for those where privacy is limited to sparse leafless bushes, and for those subjected to the buzzing gaze of a fellow diver’s drone. Women divers may also want to consider that perhaps different nappies may be needed for different types of diving.

The major downsides include possible leaks, discomfort, increasing bulk (when wet), skin irritation, increased risk of infection, and embarrassment. Also, depending on the type of nappy—tabbed or pull-up—they may present challenges between dives because of privacy issues. Nappies may not be the optimal choice for the environmentally conscious since they are not recyclable. Disposal during remote and/or expeditionary diving may also be inconvenient.

Leakage is generally a consequence of poor fit and/or inadequate absorbency. A healthy woman may experience a normal urge to urinate at approximately 300-400 ml and a strong need at about 400-600 ml.2 Even with the right fit, overflow can occur if the capacity of the product is inadequate for the diver’s urination needs and/or intended for light to moderate bladder leakage (e.g., such as during a sneeze) rather than sudden normal continuous flow. The risk for leaks is less likely with slow or intermittent streams, but the same could be said for all external urine collection devices. While nappies have both benefits and drawbacks, it is important to note that they may also be the only option for some divers who cannot use external catheter systems.

External Catheter Systems

External catheter systems have three main components: the external collection device (ECD), a catheter (tubing), and a discharge or relief valve (also called the P-valve), where the urine exits (Image). The ECD is the human-catheter interface that connects the external genitalia or pubic area to the catheter. For men, the ECD is a disposable sheath that fits over the penis like a condom with an opening at the tip to allow drainage. Condom catheters come in a surprising variety of different sizes, shapes, materials, and adhesive options (e.g., self-adhesive WideBand and Freedom) depending on the medical manufacturer. The ECD for women is a reusable one-size-fits-all elongated cup-like reservoir manufactured by either She-P (Fred Devos, co-owner of Zero Gravity Dive Center originally coined the name in 2007 after seeing a prototype), or SheWee Go.

The She-P reservoir is a handmade, medical grade, hypoallergenic silicone device encircled by a flat rim that is adhered to the skin using medical grade adhesive. The material is soft, allowing the shape to be altered somewhat by the user. The newest She-P version 3.0 has evolved to include slight concave modifications to the shape of the rim from the She-P Classic. The SheWee Go is a natural gum rubber device with a rounded ridge and is secured, rather than adhered, in place with three adjustable straps. Both male and female ECDs connect to a catheter allowing urine to flow toward the P-valve attached to the drysuit’s upper leg.

The P-valve is either balanced or unbalanced. The primary difference is that balanced valves remain open during the dive, allowing the pressure inside the catheter to equalize throughout the dive; whereas unbalanced valves remain closed (except for during urination). Unbalanced valves must also be primed (pre-dive urination) to remove the air space in the catheter. The urine passes through the tube, out the valve, and away from the body. Women are often advised to use balanced P-valves. It has also been suggested that the risk of complications with a P-valve may be less with a balanced valve.

According to informal online surveys on two Facebook groups (“Girls That Tech Dive” and “Cave Diving Mermaids”), a majority of participants stated that they used a She-P either alone or with backup leakage protection (e.g., nappy, an incontinence pad, or maxi pad). A review of various online retailers also seems to indicate that the She-P is more readily accessible. Alex Vassello from Custom Divers, and creator of the SheWee Go, admits that the only way to order a SheWee Go is through Custom Divers. He also feels that limited advertising and online resources may affect its visibility in the market, especially with new divers.

It is unclear whether accessibility and marketing strategies are influencing popularity or if it is the effectiveness and/or convenience of the devices. These two products have never been tested by a third party, so it is unclear how these two would compare in a dive-for-dive test. Although the She-P seems to be more common, both devices have individuals who prefer one to the other, and both have their benefits and challenges.

Vassello feels that one of the limitations of the SheWee Go is that it is less effective and more prone to leaks if used in a seated position. While Kristen Matlock has used a She-P for all terrain vehicle (ATV or side-by-side) racing in the past, she prefers a new disposable catheter system that has not hit the market yet. A number of women also mentioned that sitting in the She-P can be uncomfortable and most urinate either standing or in proper trim (horizontal body position) while diving.

The Decision to Opt-Out

Whichever ECD was preferred, women reported that they did not use it on every dive. Depending on the goal of the dive, location, dive profile, environmental conditions, personal tolerance, and the ECD itself, the urination challenges divers had to consider varied. Becky Kagan Schott, five-time Emmy award-winning underwater director of photography, technical instructor, and owner of Liquid Productions, says her strategy involves planning dives to be short enough to eliminate the need to rely on anything, or nappies at most. “If I think the dive will run over 3 hours, or I’ll be suited up that long, I’ll decide on the diaper or She-P depending on where I’m diving,” Schott said. While she prefers to not use anything, she knows that is not always possible.

Each diver’s pre-dive urine ritual when diving without an ECD is as unique as the diver. Like many women, Lyzz Rooney, an instructor with UnderH2O and an operating room RN in Portland, urinates immediately before donning her suit if she is not applying the ECD. However, location matters, and she always dons the She-P for boat dives. “I can’t take my clothes off and dangle my bits off the side without embarrassment,” Rooney joked. Lauren Fanning, GUE instructor and marketing manager at Halcyon Diving Systems, uses her She-P for longer dives, no matter the location. But Fanning still makes sure she is appropriately hydrated and employs a ‘rule of three’ before getting into the water, urinating at least three times before the dive to ensure she can manage. She also emphasized that the ECD is an important piece of equipment for technical diving and that she “wouldn’t go into the water without a breathing device…[or] without the ability to urinate during a long dive.”

Female divers were more inclined to don ECDs on longer dives or when breaks between dives were considered too short. Long dives were defined by the length of time one could wait without having to urinate (the threshold) and the decompression obligation that would be incurred. According to survey participants, the threshold ranged from approximately 90 minutes to four hours. Good urination management is especially critical since divers may want to rest on the surface following decompression diving in order to off-gas before exiting and/or lifting heavy equipment. “When I’m teaching, most of the time I don’t bother with a [She-P],” explained Marissa Eckert, a tech and rebreather instructor and co-owner at Hidden Worlds Diving. However, “I’ve done 11-hour cave dives; a diaper will not stand up that long.” Rooney, on the other hand, who has been using a She-P for about 10 years, said, “I hook up every day of instruction since I know I’ll be in a suit for six or more hours.”

Nathalie Lasselin, cinematographer and explorer, spent two 15-hour days diving 70 km (43 mi) of the Saint Lawrence River in Québec. The Urban Water Odyssey, to bring awareness regarding water quality in Québec, involved over a year of planning, multiple sponsors, and a multi-member support team. A leak could have put an end to her carefully planned dive. After considering her options, she chose to dive with a She-P and backup. While she considered using an internally placed catheter, she was concerned about a catheter system failure, retrograde flow, and direct inoculation by cold, bacteria-filled river water.

Lasselin faced another challenge when the back of the device became unglued, a common issue experienced by She-P Classic users. Lasselin was also using a diver propulsion vehicle (DPV) attached to a crotch strap, which meant the strap was applying “constant friction and tension at the wrong place.” Laura James, the North American representative for She-P, stated that “tight harness waist belt/crotch strap combos…can contribute to success or failure rate.” Lasselin admits that the She-P did not work 100%, but it was the only option she felt she had. Her strategy also included adding various layers including two thongs (on each side of the She-P), a nappy, and latex underwear to secure the She-P and to contain leaks.

Extended dive times (e.g., dives greater than five hours) are likely to be beyond a diver’s threshold. Divers were also less inclined to withhold fluid intake in order to lower urine output prior to performing dives with decompression obligations. The primary concern reported was the potential impact that dehydration may have on the risk of decompression sickness. “Much of diving is about risk (uncertainty) management,” states Gareth Lock, owner, trainer and coach at Human in the System Consulting/The Human Diver. Lock feels that “divers try to limit their DCS risk by being correctly hydrated, and the use of an external catheter system allows that to be managed relatively well in male divers. Despite this, there are numerous stories of male divers not having a urination system and not hydrating properly as a consequence. For female divers, the solutions afforded to them are not the same.”

Nappies on their own “have limitations, especially for protracted and/or decompression dives,” said Nelly Williams, technical diver and co-owner of XOC-Ha in Yucatan, Mexico. Williams opts for the P-valve on longer dives “where proper hydration is essential.” Consequently, extended dive times and/or prolonged decompression might result in greater urine output. The increased output may be problematic if a low capacity nappy is used because the volume produced might be more than it can absorb. This could potentially lead to leaks or expose the skin to urine for a prolonged period of time.

To She-P or She-Wee?

According to Deborah Johnston, cave explorer with the Sydney University Speleological Society, motivation to use her She-P was dependent upon finding a balance between the perceived challenges and the benefits of being able to urinate during the dive. The decision to ditch or don the She-P was generally based on whether the dive time was long enough to tolerate the challenging site preparation and cleanup. She-P proper site preparation requires hair removal, removal of oil and moisture from the skin, application of an adhesive, and proper placement of the device. This still does not guarantee a leak-free dive, and the ECD or P-valve may still fail which may present a thermal risk to the diver. A majority of survey participants reported leaks, primarily from the perineum (backside). Although women used back up protection to manage leaks, they also expressed discontent with the need for the backup and the extra waste is created. Cleanup refers to the removal of adhesive residue and cleaning and storage of the ECD. “Cleaning up adhesive afterwards is my biggest complaint with a She-P,” Fanning admitted. Her frustration with the aftercare and adhesive cleanup is mirrored by many women.

Lyzz Rooney trying to use her female urination device with a drysuit in between students open water certification dives. Photo by Jonathan Fletcher.

Ease of use and good fit were the primary reasons cinematographer and explorer Jill Heinerth has been a SheWee Go user for over six years. While she admits there is no perfect solution, she “has had better luck with the SheWee Go and feels more comfortable” with it. Heinerth also admitted that site preparation and the need to glue the She-P in place seems particularly impractical in expeditionary diving. Indeed, women reported that frustration with site preparation and cleanup, poor device fit, and the likelihood of experiencing a leak were deciding factors for choosing the SheWee Go or nappies.

Availability can also be an issue. Gemma Thomas, an instructor located in Singapore, reported that the medical adhesive needed for the She-P was not available in that country. In addition, mature women may experience vulvovaginal atrophy as estrogen levels decline. Symptoms may include thinner, less elastic, and drier vulvar and vaginal tissues4. Changes may also occur following hormonal therapy which also makes the SheWee Go or nappies a potentially good option for some, since removing the device may lead to abrasions or tearing. One diver, who will remain anonymous, said that for her nappies were the only solution following estrogen reduction treatment for breast cancer.

Challenges and complications

Ideally, an effective ECD should be easy to apply and use, should perform without leaking, and should keep the skin reasonably dry. A device that is simple to maintain is a plus. Most importantly, ECDs should function without causing discomfort or injury. Unfortunately, the perfect option currently does not exist. Application and leaking seem to be the greatest sources of frustration with the external catheter ECD systems, although this is hardly an issue for women only. A 2010 survey of (predominantly male) pilots flying for the U.S. Air Force U-2 Reconnaissance Squadrons reported that 60% of individuals had problems with their ECDs including poor fit, leaking, and skin damage from extended contact with urine.5 Rooney added that while she has had leaks and P-valve failures, “the boys have had their fair share of both leaks and catastrophic failures [and] have their own trust issues with their systems too.”

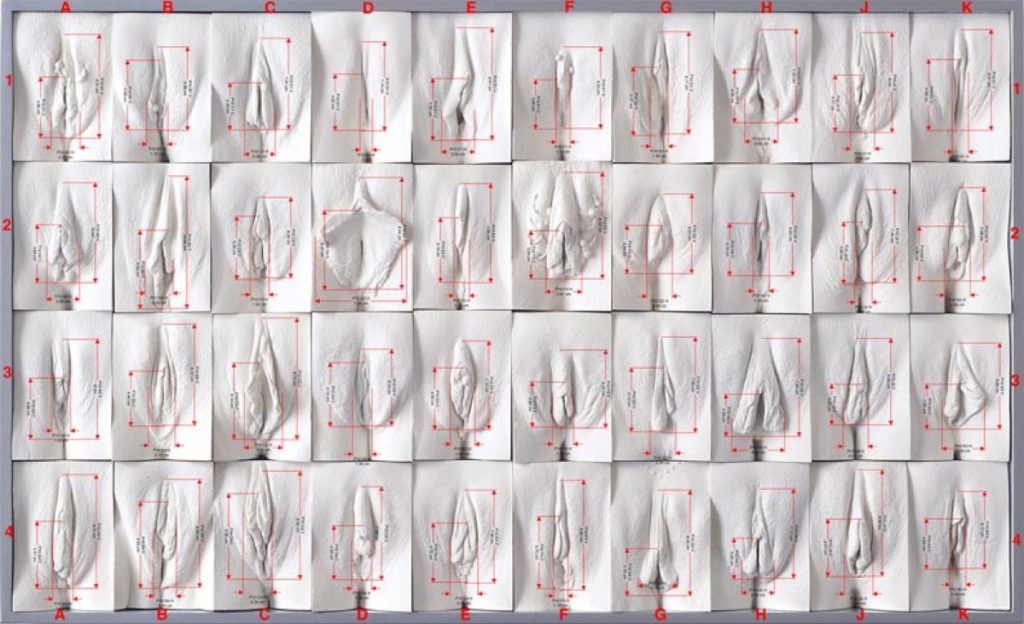

That women suffer from poor fit and leakage should come as no surprise given the variation in female genital anatomy and the one-size-fits-all approach of ECDs. A quick review of biomedical literature available through PubMed returns measurements for normal female genital variation based on various factors including race, age, weight, and hormonal changes. Wendy Grossman, who has been cave diving for over 16 years, feels that not everyone understands that “not all vaginas are made equal.” Grossman wore a She-P for about 10 years before deciding to use nappies exclusively.

It seems that female anatomical variation may be underappreciated or perhaps under-recognized by ECD producers and female consumers alike. In fact, the lack of appreciation even inspired Jamie McCartney’s 2011 wall sculpture “The Great Wall of Vagina,” a 10-panelled wall sculpture comprised of the plaster casts of genitals from 400 female volunteers. Both Vassello, creator of the SheWee Go, and Heleen DeGraw, creator of the She-P, do feel that human error plays a role in failure rates. While leakage may be due to poor adhesion caused by improper area preparation, equipment interfering with the seal, and with general challenges placing the device, the real challenge may just be that one size does not fit all.

Other concerns reported with She-P use include skin irritation/burning caused by the adhesive, which are typically due to contact between the glue and freshly shaved/waxed skin. Rooney found that “on really long days with multiple dives, I’m prone to more leaks.” Women reported discomfort from having to sit on the ECD during surface intervals. Cases of catheter squeeze, urinary tract infections, and pneumaturia has also been reported with P-valve use in both men and women.3 According to personal reports, catheter squeezes were due to accidental closure of a specific type of P-valve (balanced valve) or deliberate closure in response to a leak prior to ascent. In these cases, the pain was accompanied by bruising.

Final considerations

While external systems provide the convenience of being able to urinate without disrobing, divers must consider the unique challenges associated with their environment. Immersion, pressure changes, and equipment restrictions can contribute to complications, particularly for women. Effective urination solutions are important not only for comfort but for functional and safety reasons as well. Divers ready to consider using an external urine collection device should talk to other divers, review available resources, and consider the possible tips and tricks available.

Tips for New Divers

- Don’t be afraid to ask questions; it may be an uncomfortable subject for some, but one that women should be free to discuss.

- Know your body: pay attention to your fluid intake, urination needs, and how environmental conditions impact your threshold.

- Test your preferred external urine collection device in the shower before your dive and perhaps take it for a dry test run.

- Choose the right tool for the job: make sure your nappy is the right size and has the correct capacity for the dive.

- Consider adding cleansing wipes to your tool kit: use them prior to She-P placement to remove oils from the skin or after to remove adhesive residue. Wipes are also useful for managing any accidents.

- Give yourself enough time to prep for She-P placement and to allow the glue to adhere properly.

- Perform a pre-dive system test: once you have donned your gear, ensure your P-valve system is functioning prior to entering the water.

- Adjust volume control: fully relaxing may cause the ECD cup to fill too fast creating some back pressure, possibly leading to leaks.

Footnotes/References

1. XPMedical [Internet]. Adult diaper reviews; [cited 2019 July 16]; [about 3 screens].

4. Marnach ML, Torgerson RR. Vulvovaginal Issues in Mature Women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017; 92(3): 449-54.

5. Von Thesling GH, Coffman CB, Hundemer GL, Stuart RP. In-flight urine collection device: efficacy, maintenance, and complications in U-2 pilots. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2011; 82(2): 116-22.

Payal is a doctoral student in kinesiology at Université Laval exploring the impact of extreme environments on physiological adaptation, human performance, and health and safety. She is also a certified technical and cave diver. Her background in public health education and training as an Emergency Medical Technician guide her efforts to develop communication, outreach, and education products that use physiological concepts to improve diving safety.

Dive Deeper:

“The Divine Secrets of the She-P Sisterhood” by Michael Menduno (DIVER August, 2010)

Divine Secrets of the She-P Sisterhood, Episode 1: “What’s In the Kit?”

Divine Secrets of the She-P Sisterhood, Episode 2 Part 1