Cave

Celebrating Wes Skiles

This month we explore and celebrate the extraordinary life and work of cave diving pioneer, explorer, conservationist, and underwater cinematographer/ photographer Wesley C. Skiles.

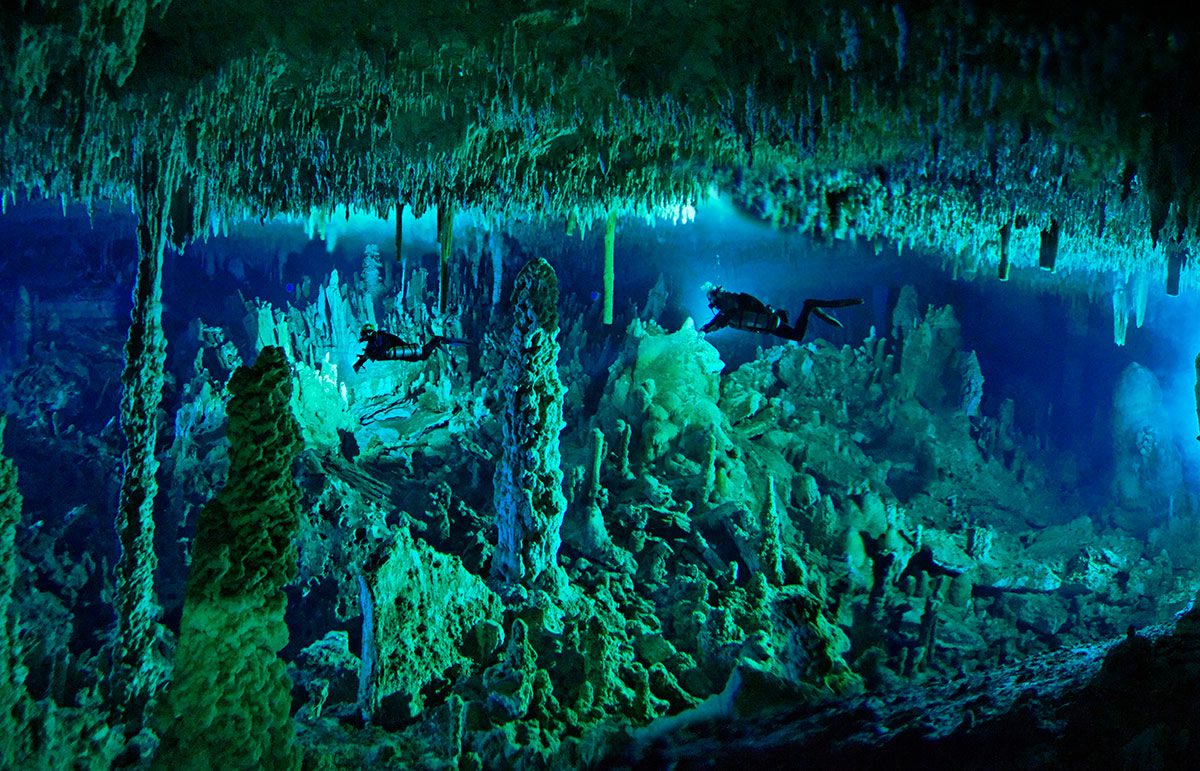

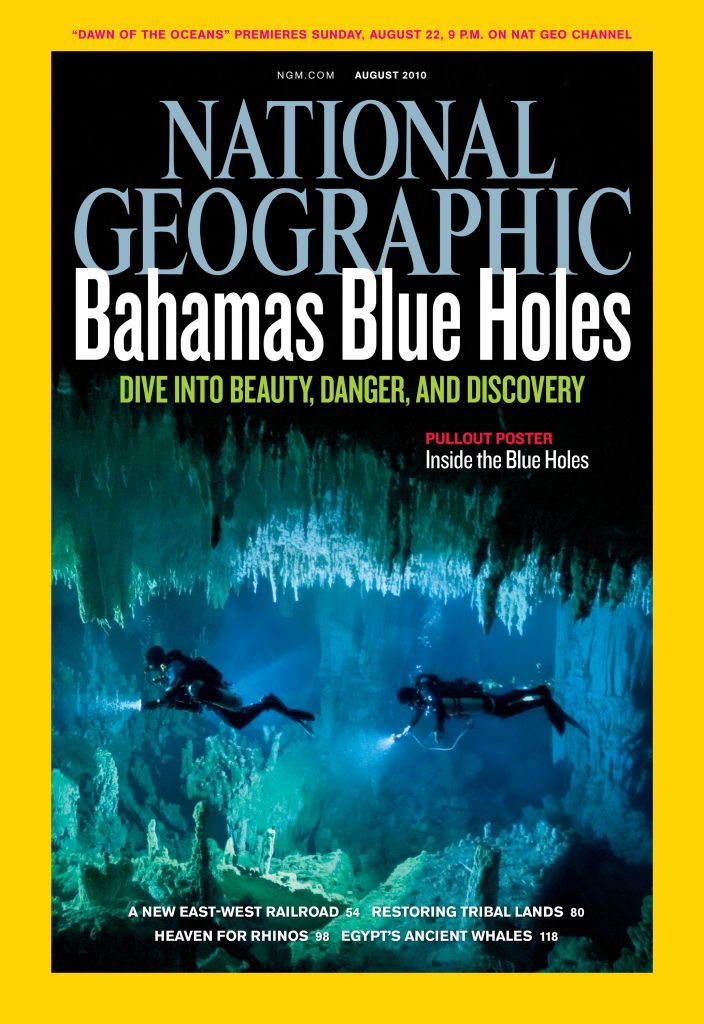

Text by Michael Menduno, graphic design by Amanda White. Header image from the cover of National Geographic August, 2010 by Wes Skiles: The Cascade Room leads divers deeper into Dan’s Cave on Abaco Island (see details below).

🎶🎶 Predive Clicklist: Black Water by the Doobie Brothers

“I was adding it up recently, and I have surpassed 500 miles of virgin exploration in my career. I’ve been in, and laid line—the first line ever—in 500 miles of virgin cave. That’s a lot of going places no human has been before. In a world where almost everything on the planet has been explored, it’s like discovering a state the size of Florida and being the first person on Earth to walk its entire length from the Panhandle to the Florida Keys. I’ve done this underground, under water.”—Wes Skiles, Currents, May 2010

This month we explore and celebrate the extraordinary life and work of cave diving pioneer, explorer, conservationist, and underwater cinematographer/ photographer Wesley Cofer Skiles, who was born March 6, 1958, in Jacksonville, Florida. He died July 21, 2010 at age 52, in a rebreather diving accident in 18m/60 ft of water near Boynton Beach, Florida, while on assignment for National Geographic filming scientists feeding Goliath Groupers. His tragic death resulted from what could be described as a perfect storm of human factors.

Skiles not only had a seminal impact on the development of cave diving but was also instrumental in helping scientists and policy makers see and understand the importance and role of underwater springs in the workings of the Florida aquifer, as well as to shed light on public awareness of the underwater world.

Working through his company, Karst Productions, the prolific documentarian produced over 100 films and TV shows including Nullarbor Dreaming (1989), which documented the harrowing escape of 15 entombed cave divers from a flooded Australian cave—the film inspired James Cameron’s film Sanctum; Journey into Amazing Caves (1990) with award winning documentary filmmaker Howard Hall, and Ocean Spirit (1995), which chronicles Skiles’ 3,500 mile ocean trek aboard a 110-ft sailboat with Grateful Dead drummer cum scuba diver Bill Kreutzmann. There’s also his Emmy-winning, four-part PBS documentary series, Water’s Journey (2003-2006) about the Florida springs and Everglades, and four conservation stories for National Geographic (NatGeo) beginning in 1999. These led to his first and final NatGeo cover story, “Bahamas Blue Holes” that was published August, 2010, days after Skiles death. He never saw the printed copy.

Hooked on Cave Diving

You could say that Skiles’ life work and passion was set in motion in 1971, when the then-13-year old surfer and newly-certified YMCA scuba diver conducted his first cave penetration dive and simultaneously took his first underwater photograph at Ginnie Springs in High Springs, Florida. He used a Nikon camera that an onsite photographer handed him to try while his older brother Jim piloted a prototype underwater scooter built by his science teacher. “Everyone told me, “Don’t go in the cave,” Skiles recalled. “But I went in the cave. I got this shot of my brother scootering past the entrance and the shot came out really good. I was hooked from that point on.”

In less than a decade, Skiles, who first completed his open water instructorship, became a cave diving instructor with the National Speleological Society-Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS) and took a job managing Gene Broome’s Branford Dive Center. There he met Lamar Hires in 1979 and saved his life by gifting him a copy of Sheck Exley’s Blueprint for Survival after Hires barely survived running out of air making a cave penetration with a single cylinder. Skiles took him under his wing and taught him cave diving.

Skiles, and soon after Hires were engaged in building their own diving equipment such as dive lights—there were no cave diving manufacturers at the time. Later, they both worked with Woody Jasper, Tom Morris and others to develop sidemount diving equipment. Hires, of course, continued to invent and build gear, and went on to launch Dive Rite in 1984. Skiles left Branford to become manager at Ginnie Springs in 1983, and the following year also became the training director for the Cave Diving Section (CDS) at the tender age of 26, a position he held for five years. He launched his production company, Karst Productions in 1985.

Not surprising, with legendary cave diver Sheck Exley as his mentor, Skiles was passionate about cave exploration and produced a series of maps and of his explorations of Little River, Rock Bluff, Jug, Bonnet, Cow Springs, and more, which were made available through the CDS. As hydrologist and fellow cave diver Todd Kincaid recalled with a chuckle, “Wes’s philosophy was to try and not leave anything for the next generation to explore.”

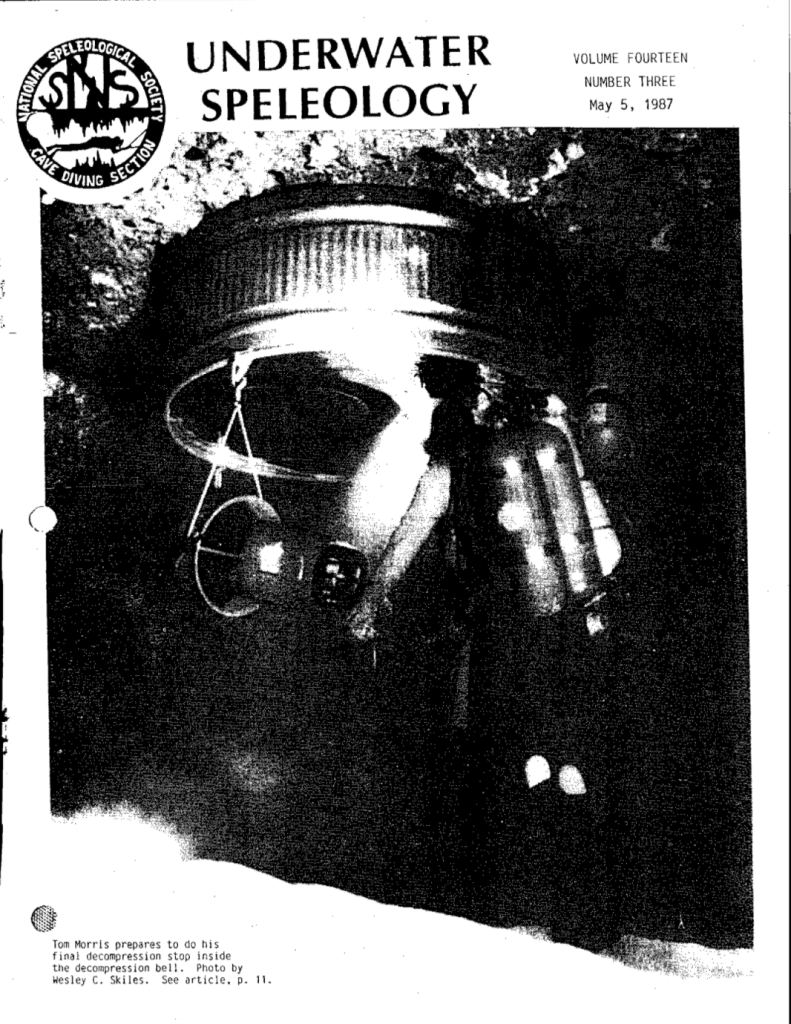

Skiles published a prescient article, “The Scientific Future of Cave Diving,” in the Vol 14, #3 May, 1987 of Underwater Speleology (UWS). The article outlined the potential role of citizen scientist cave divers in data collection and detailed numerous methods i.e., field surveys, dye tracing, water chemistry, biological and geological collection. The article goes on to outline the basic arguments for nitrox and mixed gas diving, and the use of decompression bells, all of which would be needed, argued Skiles, if cave divers are to go deeper and stay longer.

His insights were not lost on caver and fellow Exley protégé Bill Stone, who launched his ground-breaking Wakulla Springs Project—arguably the equivalent of a technical diving moon-shot—that Fall. Skiles was both a member of and worked with Stone’s US Deep Caving Team and documented the Wakulla Project expedition, Stone’s 1994 San Agustin expedition to Sistema Huautla in Oaxaca, México—an exploration project that continues to this day under Stone’s leadership—and his return expedition to Wakulla, dubbed Wakulla 2, in 1998, with then fledgling explorer-in-the-making, Jill Heinerth. Skiles was also involved in the filming of Mike Madden’s Nohoch Nah Chich project, and the race between competing cave groups to connect Nohoch to Dos Ojos in the mid-90s.

Where Does The Water Come From?

Skiles was the first to show geologists, hydrologists, and policy makers what underwater springs actually looked like and presented data regarding water movement. At the time, scientists thought that the role of the springs in the aquifer was insignificant; in fact, initially some believed Skiles’ underwater video was faked. Nevertheless, Skiles was enlisted and served as a member of the state’s Florida Springs Task Force where he spent years lobbying for spring conservation. The year after his death, the state of Florida renamed Peacock Springs State Park the Wes Skiles Peacock Springs State Park.

NatGeo published 15 of Wes’s images in its story, “Unlocking the Labyrinth of North Florida Springs,” in March 1999, which brought attention to the plight of the Florida’s springs. This led Skiles, while working with protégé Jill Heinerth, to create the Water’s Journey documentary series for PBS (2003-2006) several years later.

Skiles went on to contribute images for NatGeo’s December 2001 story, “Islands of Ice,” with help from NatGeo’s legendary deep sea photographer Emory Kristof, who had met Skiles through Stone’s Wakulla Springs project. He worked with Jill and Paul Heinerth and Bill Kurtis, and was the first human to stand on the B-15 iceberg, which was the largest known iceberg at the time. Jill Heinerth wrote about the expedition in Ice Island, published in Advanced Diver magazine, and later Skiles, Kurtis, Heinerth, and Kristof produced the Ice Island documentary.

In 2003, Skiles supplied 17 images for NatGeo’s Oct 2003 story, “Watery Graves of the Maya.” He later worked on the magazine’s Blue Holes cover story with environmental anthropologist Kenny Broad, Heinerth, and explorer Brian Kakuk. In his Editor’s note, editor-in-chief Chris Johns said of Skiles, ”He set a standard for underwater photography, cinematography and exploration that is unsurpassed. It was an honor to work with him, and he will be deeply missed.” In 2011, NatGeo named both Skiles and Broad, “Explorer of the Year.”

I met Wes in the early 1990s, after starting my magazine aquaCORPS Journal. He penned a piece, “Deep D(r)iving Motivations: A Personal View,” on deep air diving for our Winter 1991 issue #3 DEEP (Feeling lucky?) and was always generous with his time and photos. His images graced the cover of aquaCORPS #11 Underground Xplorers (OCT/NOV 1995) issue. I was also fortunate to attend one of Wes’s legendary backyard bonfires. That night he pulled out his harmonica and played, while someone accompanied him on acoustic guitar.

I last interviewed Wes over the phone for a DIVER magazine story a month before his passing. The story was about the She-P and diver urination systems, and I asked Wes how he and fellow Wakulla drysuit divers peed during those long ten to twelve hour dives—this was before condom caths. There was a moment of silence. “Us manly men were too stupid and or embarrassed to slip on diapers,” he told me in his Floridian drawl. Instead, they held their bladders until they could pee out the habitat doorway just before changing depths, which would act as a flush. Note, Exley stuck with his wetsuit and chemical heaters.

Seeking Skiles

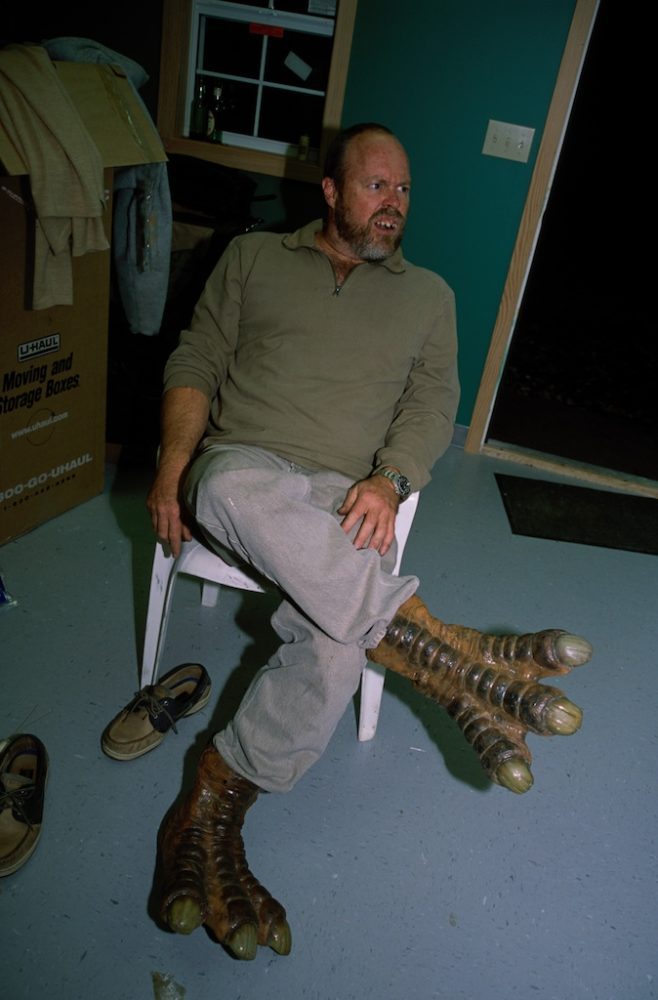

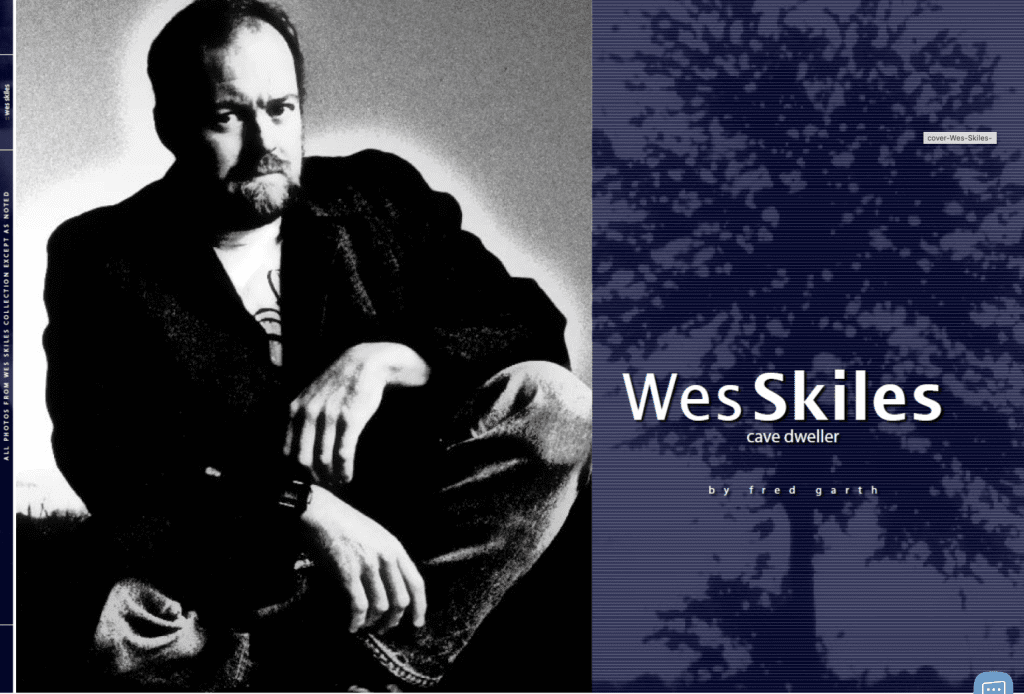

In this issue of InDepth, we offer you a curated selection of stories both old and new about Wes Skiles, beginning with this 2002 long form interview by Fred Garth, Wes Skiles: Cave Dweller,” which was immortalized in Gilliam’s book, Diving Pioneers and Innovators. Next, we offer an excerpted chapter, Water Boy, from Julia Hauserman’s 2018 book, Drawn to the Deep, the Remarkable Underwater Explorations of Wes Skiles, which tells the story of Skiles’ first cave dive and underwater photo. Stoned: The Adventures of Wes Skiles and the US Deep Caving Team, features a selection of Skiles’ iconic images from Wakulla Project 1987, the 1994 San Agustin expedition, and Stone’s 1998 Wakulla 2 expedition, along with a tribute from Stone.

We also have stories from three colleagues who worked with Skiles; Wesley C. Skiles: Extreme Cool by Emory Kristof, To Wes: A Tenacious Advocate Committed To Protecting Florida’s Springs by Skiles’ contemporary, hydrologist and cave diver Todd Kincaid, who discusses the impact of Skiles’ work on Florida water conservation, and The Inimitable Wes Skiles, which presents a set of unique photos of Skiles and a sentiment from Jill Heinerth, that appeared in TEKDive USA’s Pushing the Envelope historical tech photo exhibit.

We have included a selection of key Skiles’ Films and Videos, for you to dive into; Nullarbor Dreaming, Ice Island, the Water’s Journey series and more, along with several In Memoriam videos and a recording of the memorial services held for Wes at Ginnie Springs 28JUL 2010. In addition, there are links to important Articles by Skiles and others, including a selection of NatGeo (subscriber content).

The NSS-CDS has also graciously provided the special issue of Underwater Speleology V 37 No. 4 OCT/NOV/DEC 2010, Remembering Wes Skiles (1958-2010) which includes a dozen tributes from his peers. There’s also information on how to participate in The Wes Skiles Legacy Project, organized by Wes’s daughter Tessa Skiles.

We want to offer special thanks to David Concannon, NatGeo’s Image Archivist and Rights Manager Rebecca Dupont, UWS editor Barbara Dwyer, Fred Garth, Bret Gilliam, Larry Green, Howard Hall, Julie Hauserman, Jill Heinerth, Lamar Hires, Todd Kincaid, Emory Kristof, Gareth Lock, Fan Ping, Brian and Marcia Skerry, Terri and Tessa Skiles, Bill Stone, and the NSS-CDS board for their help pulling together this remembrance.

We celebrate you, Wes Skiles!

Wes Skiles: Cave Dweller

by Fred Garth and Bret Gilliam

Water Boy

An excerpt from Drawn to the Deep: The Remarkable Underwater Explorations of Wes Skiles

By Julia Hauserman

Wesley C Skiles: Extreme Cool

By Emory Kristof

The Inimitable Wes Skiles

By Jill Heinerth

Films and Video

NSS-CDS: Nullarbor Dreaming, the amazing story of a cave diving team in far west Australia trapped underground by a storm that caused a passage collapse. Produced by Andrew Wight, photography by Wes Skiles. 1989

MacGillivray Freeman Films (1990): Journey into Amazing Caves You can find the film on Amazon Prime

Entertainment Tonight (1995): Ocean Spirit

New Explorers with Bill Curtis (1995): The Most Dangerous Science.

Wes Skiles and Jeffrery Haupt for the PBS series New Explorers featuring the Nohoch Cave Diving Team and their connection of the Nohoch cave system to the sea.

Ice Island Expedition (2004)

The Ice Island expedition gave our team the opportunity to test some remarkable new technology. Wes Skiles brought the beauty of High Definition cinematography to the film, using it in some of the most extreme environments one can imagine. I brought advanced closed-circuit rebreathers to the diving operations that allowed us to physically penetrate caves inside of massive, moving icebergs. It was some of the most challenging and dangerous diving ever conducted, and bringing home the images in the glory of HD detail was something that will not likely be repeated!—Jill Heinerth, Producer/Exploration Diver

Water’s Journey: Hidden Rivers of Florida (DEC 2003)

Over eight billion gallons of water a day bursts forth from Florida’s springs – the most unique concentration of springs on the planet. At one time, it was thought to be an endless supply, but now the demands of man are starting to exceed availability. We join a team on a daring journey into the Floridan Aquifer to find out what’s going wrong. As the team follows the connective path of water through the landscape, their discoveries lead viewers on a thrilling adventure about the miraculous course that water takes, and the places we don’t want to believe it goes. Buy a DVD here: Water’s Journey

Water’s Journey: The River Returns (OCT 2005)

Utilizing some unusual views high above and deep within the earth, a team of explorers completely immerses themselves in the mechanics of a river system on a quest to define the nature and source of its powerful flow. Their adventures reveal the stunning beauty of a wild and scenic land and the difficult issues facing the populace as they grapple with the reality of inevitable growth. The River Returns inspires hope that the great watersheds of our planet can be saved, and that environmental protection and sustainable growth can coexist in a new paradigm of cooperation. Buy a DVD here: Water’s Journey

Water’s Journey: Everglades: Restoring Hope (DEC 2006)

Twenty-two million people call it home. Millions more travel to Florida for recreation, beaches and theme parks. Few know Florida is home to one of the greatest ecosystems on earth – The Florida Everglades. But this masterpiece has reached its limit to absorb mankind’s ever-growing impacts. Although people may not always agree about how to restore balance to the Everglades, one thing is clear. Humanity needs wetlands. They are the foundation of a fragile ecosystem that extends from inland waterways to the ocean wilderness. Can we achieve the delicate balance that protects humanity and the environment? Will the largest restoration plan ever attempted… succeed? Join our team of scientists and explorers as they follow the flow of the great river of grass, and beyond.

Water’s Journey- Currents of Change (DEC 2006)

Karst Productions with Wes Skiles: Springs Heartland (April 2011) • Edited by Bob Dorough for Wes Skiles and Karst Productions

In Memoriam

Wes Skiles Memorial Services: Here is a recording of the memorial held for Wes at Ginnie Springs on July 28, 2010. There were nearly 1000 in attendance.

Alachua County: Remembering Wes Skiles (OCT 2010)

Wes Skiles Tribute Video (DEC, 2010)

A Tribute to Wes Skiles SD (December 2017)

Ocala Star Banner: Wesley C. Skiles Obituary

Articles

Underwater Speleology V 14 (1987) : The Scientific Future of Cave Diving by Wes Skiles

aquaCORPS #3 DEEP (1991): “Deep D(r)iving Motvations” by Wes Skiles (1991). Skiles weighs in on deep air diving.

Outside Magazine (1996): Deeper: To the peerless Moles, practitioners of the gloomily claustrophobic sport of freshwater spelunking, the ultimate accomplishment is finding a virgin cave

Advanced Diver (2003): Ice Island by Jill Heinerth

Underwater Speleology V37 #3 (JULY-SEP 2010): Through The Lens of Wes Skiles.

Alert Diver (August 2010): Shooter: Wes Skiles by Stephen Frink

Wikipedia: Wesley C. Skiles

NatGeo (subscriber content)

National Geographic: Spectacular Underwater Archaeology Photos by Wes Skiles

National Geographic: Deep Dark Secrets: The blue holes of the Bahamas yield a scientific trove that may even shed light on life beyond Earth. If only they weren’t so dangerous to explore.

National Geographic: Dive Freshwater Caves, Florida

Remembering WES SKILES 1958-2010

In October, 2010, the National Speleological Society-Cave Diving Division (NSS-CDS) published a special issue of Underwater Speleology V 37 No. 4 OCT/NOV/DEC 2010. The issue included tributes from: Terri Skiles, Woody Jasper, Jim Stevenson, Kenny Broad, Jill Heinerth, Brian Kakuk, Tom Morris, Bill Stone, Agnes Milowka, Paul Heinerth and David Uluoa. Download the issue here: Remembering WES SKILES 1958-2010

The Wes Skiles Legacy Project

Wes’s daughter Tessa Skiles is creating a legacy web site to carry on with his work of protecting and restoring Florida’s springs. She’s looking for stories, videos, and photos of Wes (especially from the ‘70s-‘90s). If you have any, Tessa would like to include them. Send them to her at: [email protected]. Please include the subject “Legacy Website Content—YOUR NAME, STORY/IMAGES.” Please include dates, locations, and names. Thank you.

Be A Part of History: To access our treasure trove of dive history and become a member, visit us at: www.HDS.org. We are also on Facebook: Historical Diving Society USA