Cave

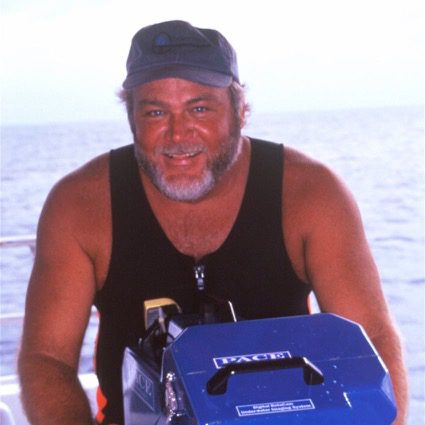

Wes Skiles: Cave Dweller

By Fred Garth and Bret Gilliam.

This interview, which was conducted in Spring, 2002 was originally published in now defunct Fathoms Magazine (2000-2007) and later published in “Diving Pioneers and Innovators” by Bret Gilliam, Encore Publishing 2007.

You could call Wes Skiles a celluloid troglodyte—a cave dweller devoted to filming the earth’s underwater Swiss cheese. A lifelong resident of a dot on the map called High Springs in the heart of Central Florida’s cave region, he can slip in and out of his role as a redneck like a well-tailored pair of overalls. For instance, if you offered Wes a turtleneck on a cool day in New England, he’d probably think it was something to make soup with.

But he can also smooth talk the Editorial Board of National Geographic and get mucho dinero funding approved to blast off to the Antarctic wilderness under icebergs. First and foremost, Wes is a world-class explorer and filmmaker. He’s been the friend and understudy of caving legends like Sheck Exley and Parker Turner, both of whom died in their element while riding the razor’s edge. He helped to invent dive gear we commonly use today and created other contraptions like an underwater decompression habitat for one of the world’s most ambitious cave exploration projects.

As a kid, Wes made surf films before moving into diving where he crafted numerous movies, including a critically acclaimed IMAX film, Amazing Caves, with Howard Hall. He was the first to dive ice caves in the world’s largest iceberg, and he’s been known to hang out with the likes of the Grateful Dead. All this, and the man’s still in his 40s. There’s probably no one on the planet who knows more about diving in cave systems, what rebreather to use, and how to record it all on film.

Skiles is uniquely successful in the decidedly niche market of cave diving. It’s a bit of a strange community. All the participants barely total the number of divers on the Cayman dive boats off the West End any afternoon. Yet it seems that, at any given time, there are bitter rivalries and feuds that make the Sunnis and the Shiites look like kissing cousins. It’s a bit hard to fathom that such a small group can frequently display such dysfunctional behavior. Wes, on the other hand, rises above the fray and distinguishes himself with his talent—both as an exploration cave diver and as filmmaker/photographer—that captures the pure adventure.

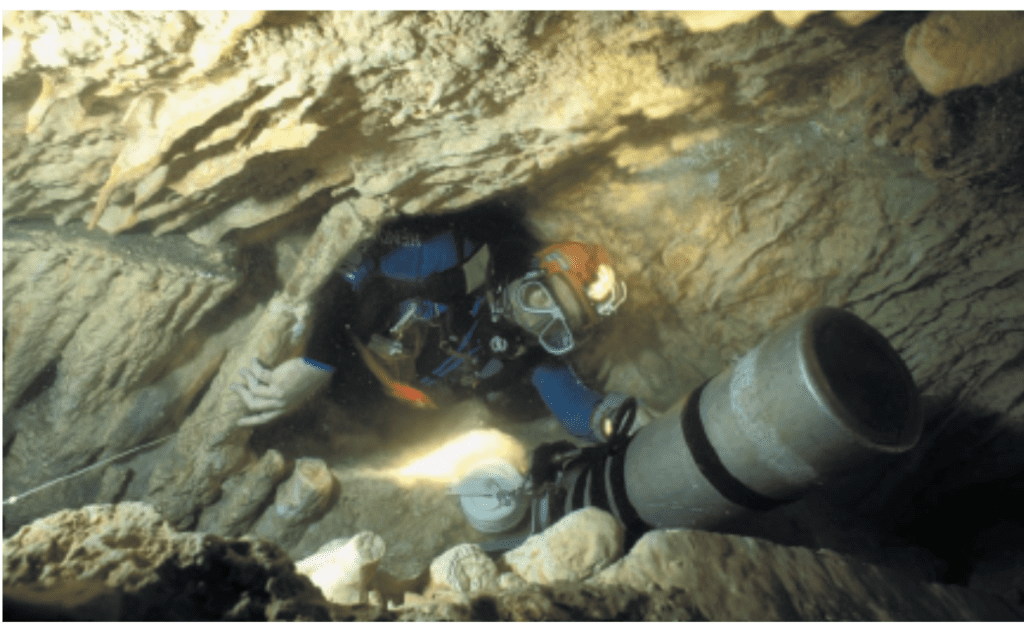

Cave diving is not for the faint of heart. It’s also not for most people in their right minds. It’s dangerous. When you’re a few thousand feet back in an underwater cave system and you have a problem… Well, generally it’s a long friggin’ way to get out. There’s no option for a free ascent since there’s a hard ceiling over your head and the only way out is the way you came in. And that may be more than an hour or so away. Lots of cave divers have tempted fate and lost. Some of the best explorers in the world have fallen victim. Skiles has managed not only to survive but to thrive in that harsh and unforgiving environment.

He also brings a sly sense of humor to his work. Anyone who’s seen his act with the filthy false teeth and backwoods Billy-Bob dialect can’t possibly stifle a laugh. He even did that to Howard Hall on the IMAX set. (This perhaps cemented Howard’s long-held suspicion that cave divers inhabit a very special trailer park out on the lunatic fringe. Wes, by the way, has a double-wide.)

For those that have seen his images and his films, there is no question that Wes is the premier master of his subterranean craft. In person, he’s funny, erudite, and a well-informed conservationist who has a deep passion for preservation of the fragile cave systems that have made his career. In the spring of 2002, I corralled him for this interview. So hang on to your scooters while he takes us on a personal tour of his life and insights into the fascinating world of underwater caves. And a few deviations along the way.

Fred Garth: How long had you been certified before venturing into caves?

Wes Skiles: Well, I really started going into caves before I was even certified. The springs around here were accessible to us and the nature of it just led us into caves. Luckily, I somehow instinctively knew to stay near the entrance and survived all that. I did my first open-water check-out dive when I was 13 where the grate is now at Ginnie Springs. That’s the way they taught scuba diving back then. We didn’t think anything about going back that far into a cave to take our mask off and buddy breathe and do ditches and dons all in an overhead environment.

When did you go from freshwater to saltwater?

Right after we were certified, we were ready to start down to the Keys and to West Palm and off Jacksonville and all that, so I’ve been diving in those places since 1973 or ’74.

Did you ever think that High Springs would become the cave diving Mecca of the world?

Ha Ha. Well, I don’t think I would have ever ventured to guess back then that this place would become the heart of technical diving and the cave diving capital of the world. It was just a place down a country road where there were some remarkable natural areas to go diving. And, back then, around every corner was a new discovery. I just don’t think we ever expected how the cave community would develop.

How much does the area’s popularity have to do with the natural resource and how much does it have to do with the people, such as yourself, who have promoted the region?

I hope I’ve never promoted the area in a way that would be negative to it. Hopefully, the efforts I’ve made have been an education to help people survive the experience around here and protect the resource. But I think it’s just a natural process that in teaching cave diving, the area gets promoted. People cut their teeth on cave diving down here, and it’s the first place they’re going to return to try out new skills and new equipment. And it’s just a remarkable place. So, with all of those factors, you get a real charmed environment for people to flock to.

What is your favorite dive near your home?

Always a difficult question, the favorite dive. Since I continue to plug away at exploring virgin caves around my neighborhood, I would have to say that my favorite dive is the exploration I’m working on right now.

That’s a good diplomatic answer.

Yeah it is. Certainly as far as falling into a spring, Ginnie Springs and the Devil’s Eye are my longest love affair and the reason I live right here next to them.

So you’re still able to find virgin springs, even today?

Oh yeah.

How much virgin territory is out there yet to explore?

Did I say there are still virgin springs and caves? I’m sorry, I made a terrible mistake just then [laughs]. No, there’s nothing left for the next generation to explore. That’s our philosophy, leave nothing for the next generations [laughs again]. No, seriously, there’s always something new to be explored out here. There’s always new territory. Technology and knowledge put together will always carry us to new distances inside of our favorite caves and help us find new places we haven’t discovered before.

So, you’re not talking about new entrances but simply further exploration of existing cave systems?

Oh no, no. New entrances. I mean, in the last 10 years, our team has explored probably 60 to 80 new cave systems from the entrance. It comes from a collective knowledge that you can only get from living here. I’ve been right here in the middle of this thing quietly looking around with my friends. We’re out on the river every weekend we can, kicking around and checking systematically every square inch. So for someone else to step in and look at this area, it’s mind-boggling. There are thousands of miles of rivers and nooks and crannies and sloughs, and you just couldn’t begin right now and catch up with us because we’ve been going at it for 20 years.

Are you finding these new caves along the river banks, rather than back in the woods or around swamps and so on?

I decline to answer that question.

So you don’t want a lot of people poking around looking for caves. Is that it?

No, they’re welcome to come explore the area. That’s not the point. Anybody that’s an explorer will find stuff. But I’m not going to sit here in this interview and provide a list of how to find caves the way we’re finding them. I don’t want to be rude about it. It’s just that we love our exploration.

It’s kind of like keeping the secret of a good fishing hole, huh?

Exactly. When people ask me where I’ve been diving, I just say the Withalaswanta Fe or Chataholawithchee. And, they’ll go, “Oh yeah, okay. I think I’ve heard of that.” And they’ll walk away scratching their heads and hope to find it on a map. Which, of course, they won’t.

I remember the first article I edited for Scuba Times in 1986. It was a piece you wrote about recovering a body in a cave. How did you get into that?

The first recovery I ever did was in 1976, right after I had met Bob Wray. I was working at Steve Matheny’s dive shop in Orange Park, Florida and Bob had seen my cave systems maps and had said, “Wow, you’ve been all through these caves.” About two weeks later a drowning occurred at Ginnie and he told the authorities that he knew somebody who had mapped all these caves. So Bob contacted me. When I got there that evening the lights were flashing in the woods and the officer said, “There’s nothing down here for you young man. Get out of here.” And Bob Wray said, “No, no, this is the guy I called.”

There were groups of divers there including Lewis Sollenberger and Mary Melton and a few others and we went in and found the first body. Later on the next day we found the second and that was my introduction to it. I was still in high school at the time and it was a real eye-opening experience.

What did that do to your psyche?

Well, I was probably mortified at the thought. It really scared me because I didn’t know how I would react. So [the time] leading up to that first recovery was by far the hardest thing. I mean my heart was racing and I was wondering why I was doing this. Then when I saw that body lying there covered in silt I was still calm. I went, “Okay, there’s the body, you know,” and nothing happened, and I was okay. Of course, I sat bolt upright in bed three or four nights after that, impacted by the fact that I’d seen such a grizzly thing. It was my first time dealing with death. No one had died in my life, and there it was in this sport I loved. But, you know, two, three, four, five, 15, 25, or 30 recoveries later, it was something that I had really adapted to. I felt it was an important part of cave diving’s responsibility to the public and to the communities and these counties where these springs are that we carry off a responsible duty and demonstrate that we can do it safely.

That Scuba Times article also had some outstanding images. What got you into photography?

I was always into it actually, from a very young age. I had land cameras as a kid, then when I was 14, I bought a Nikonos. I saved up lawn mowing money for it. But I always had a fascination for photography. I was a photographer on the yearbook staff in high school and did all of my own processing and developing, so I had a real love for that early on.

When did you make the leap to moving pictures?

Well, movies actually came first. My brother and I made surf movies before I got into diving. We were big into surfing, and I was his editor. So we would go out and film and bring home 8mm and Super 8 movies and put them together. So, through that I got into claymation and stop-action photography and did a bunch of animated things in film. So, I had that passion for it, and my brother had a friend in Hollywood who was into filmmaking, and I learned a lot from him. And then, all of our camera gear was stolen. It wasn’t conceivable that we could replace it. Our parents had helped us buy it all and they weren’t going to buy new stuff for us. So, I sort of got out of the motion picture stuff and dove into still photography.

But at some point you jumped back into film.

Yeah, I was giving a presentation at a dive show and a guy from Sony saw one of my multi-projector shows. His name was Ira Freidman and he said, “You know, you should be doing your style of storytelling in motion. And we’d like to sponsor you for a year with Sony equipment.” I said, “Okay,” and he gave me two complete setups of their 8mm equipment. And that was the beginning of the Sony 8mm format that eventually evolved into the DV format.

And what sort of housing did you use?

Well, Sony had a housing which was sort of a round yellow thing. But that same weekend I met Val Renetkins who would turn out to be a lifetime friend and partner. Val had a little thing called a Capsule 8 he’d built for the same camera. Just like Ira Freidman, Val offered me a housing. He said, “This is what you need. It has better optics, it’s a smaller package and has a wider angle lens, and so on.” So, just like that, I had a complete system.

Val Renetkins founded Amphibico, right?

Yes. He started with National Geographic and then developed Aqua Vision, which became Aquatica. Then he started Amphibico.

Are you using his high definition housings now?

I am. My philosophy has evolved, and I’m now conscious and aware that what we do and see is unique and sometimes priceless. Knowing this, it’s important to capture our experience in the highest quality format available. High definition is redefining how we look at the world. It’s an amazing technology that makes you feel like you’re actually there.

So what was the first underwater footage that you sold?

About two months after I got the video equipment, I bought a film camera from one of Howard Hall’s old buddies, Larry Cochran. Howard, Larry, Bill Lovin, and even Cousteau had been using this design of tube camera. I started shooting film with that, and I did the piece that National Geographic bought. So that was my first sale. Then the next two sales were to CBS and CNN with the Wakulla Springs Project.

So you started at the top and stayed there.

Well, I kind of always said I came in through the exit door from inside of an underwater cave. That was an environment that nobody was filming then, so at that time I was the only show in town, and it was easy to bamboozle people.

You mentioned the Wakulla Project, which I recall was in 1987. Tell us how that came to pass.

In 1985, I had written a thing called The Future of Cave Diving in which I drew a bunch of possible inventions: a habitat that you could weigh down or anchor into a cave that you could bring air in and decompress inside of. Dr. Bill Stone was at that presentation. It was an AAUS meeting in Tallahassee, and he told me about the things he was working on—the rebreather and other stuff for his cave projects— and he wanted to see if we could get together on all of these inventions for a project in Wakulla. So after a year of preparation, Bill’s amazing engineering, and our collective vision of building these things (certainly all at Bill’s hands as far as the designing and engineering) we put together the Wakulla Project, sponsored by, among others, National Geographic.

For those who don’t know, Wakulla is one of the world’s largest cave systems and it’s also located near High Springs.

Well, not too far away. It’s actually in Tallahassee, in a Florida State Park so we needed special permits and so on. They gave us two months to do the project.

What were some of the goals?

Deep penetration as well as developing a lot of technical diving techniques. I mean, up until that point in time, people had never even postulated about the possibilities of doing what we set ourselves up to do. For the first time ever, we had a real cache of mixed gas and the help of Dr. Bill Hamilton, through Parker Turner I might add. We had a set of tables that would allow us to do some remarkable dives. This was prior to decompression computers, prior to people doing these types of mixed-gas dives. We brought in German-made scooters because the scooter revolution had not yet begun, and AquaZepp scooters were the best deal to get us far back in the cave very quickly.

And so it was really a three-way show between Sheck Exley and Paul DeLoach doing a series of dives, Bill developing the rebreather, and our team of divers who were filming the scientific work and pushing the exploration. It got to be quite an adventure where we were proving good things and bad things about diving at 90 m/300 ft depths. And we learned the hard way to let go of our old ways and accept the new. Even while we were tuned into that idea, it was hard to make changes because for many, many years things had been done a certain way, and it required a lot of mind-bending and flexing to step into this new arena of diving.

But it was, by far at that time, the most adventurous cave diving ever done. In the end, Tom Morris, Paul Heinerth, and I made it 1.3 km/4,176 feet into the B Tunnel, which at that depth, no one had even contemplated going that far. It was a 14-hour dive including decompression. We had our portable habitat, the Habitent, so at least decompression was semi-dry.

The Wakulla Project kind of gets glazed over by a lot of people in today’s time. But if you look very carefully, you’ll see that was the project that changed the whole world of technical diving: the way scooters were used, the way equipment was combined, the way staging techniques were developed, the way gas mixtures were laid out in formal style for deco mixes—from the deep water deco nitrox mixes to O2 and then the deep water trimix and heliox gases we were diving. That was the beginning, the moment in time in which a big project verified and quantified that it could be done. And Bill Hamiliton’s superb book kind of laid out the blueprint. From there, guys like Jim King stood up and went right into it with the Eagle’s Nest project and then we started to see it just balloon one after the other.

So, besides kicking off the technical diving revolution, what was the coolest thing you discovered?

That the cave just kept going and going. It was the dream and the hope—I mean, when I was getting ready for that project, I remember laying in bed and dreaming about endless big tunnels, and passageways going everywhere, and the sensation of flying and that’s exactly what we found. When we left, it was still going, so it was that big dream fulfilled. Flying through those big rooms and being able to film it all was incredible. I shot a lot of 16mm film and stills during that project. For me, the really exciting part was making history and being able to document it all.

As I recall you made history of a few cameras as well.

Yeah, we had a couple of things happen. One time the camera was tilted inside of the housing so we shot an entire day’s worth of footage and it was all blurred. Then we had the Benthos camera, which was used on the Titanic Expedition. It had just come off of that project and was given to us by National Geographic. Two of the magazine’s long-time photographers—Al Chandler and Emory Kristoff—were there when that camera was passed on to me. And so I’m kind of boasting, “I’m using the camera that was used on the Titanic.” I was pretty proud. When I asked them about maintenance they said, “No, no, don’t do anything.” And I’m thinking, “Boy that doesn’t sound right. I don’t know that they understand how sandy and silty our environment is.”

But I wanted to do exactly what they told me, so I didn’t do anything. On one of the next dives the camera flooded. But Bill Stone, being infinitely resourceful, somehow cleaned it up and put it back together. So, I took it on the next dive and this time it caught on fire. We were at 90 m/300 feet and basically had a bomb on our hands. It was smoking and I could see sparks flying around inside the housing. So I literally dumped it off. We were loaded up with line, and since we couldn’t do any photography, I said, “Yahoo, let’s go,” and that ended up being the deepest penetration we did on the project. So it’s kind of a bittersweet story.

How has your luck been in getting more loaner cameras from Emory Kristoff?

Pretty good, really. We recovered the camera and I made a big impression when I sent it back with a note inside that just said, “Oops.”

Was the camera flood the freakiest thing that happened?

No, there were several close calls, all related to gas management. I built this sled that held tanks to the bottom of the AquaZepp, and one time I just ran flat out of gas. As I was trying to figure it out, I kind of fell calmly all the way to the bottom into the silt at about 90 m/300 feet. We were back about 366 m/1,200 feet in the tunnel and that was really scary for my partner on that dive, Clark Pitcairn. He watched me go down into the silt and he was kind of like, “Come on Wes, come on Wes, get out of there.” When we got back to the Habitent, he told me that he was going to get out of the project. He said, “When I saw you falling down there, I realized that I didn’t have it in me to help you. I have kids, and I didn’t want to die.” I said, “Hey man, I respect that completely, and I understand and embrace that.” I didn’t have any ill feelings at all.

Wait a minute, you said you ran flat out of gas and fell into the silt, but how’d you get out?

Oh, did I glaze over that? I was able to switch to my back mounted gas, and I ended up having plenty of gas. It was just a matter of getting used to the equipment.

Sheck and Paul had a problem too, right?

Yeah, they were still trying to hang on to their old traditional trimix gases. They both fell into a narcosis and oxygen problem. The scooters failed on them and they got tangled into some line and we were all cognizant that they were very late. There were some tense moments, but through Sheck’s perseverance and Paul keeping his head in what was a really mind-numbing experience for them, they were able to make it back. They ended up going through the various safety bottles we’d left behind. And they made it from stop to stop and finally back to the surface. At that point we drew a line in the sand and said, “There’s no more old-style diving with trimix.”

What was the problem with trimix?

It wasn’t a problem with trimix, just the mixture that they choose to dive. Essentially, they were diving with too much nitrogen and oxygen in their mix, and it was almost lethal. We were using an 86/14 heliox (86% helium, 14% oxygen), which totally eliminated nitrogen, so the narcotic effect was gone, and we took the oxygen down to a level that reduced the risk of oxygen toxicity. So that’s what we all used from there on out.

How did you know to use that mix?

Well, at first we were trying to use the Navy tables, and my friend Parker Turner came to us and said, “Hey guys, you’re going to kill yourselves trying to do this with Navy tables. You’ve got to meet this guy Bill Hamilton.” Parker had been out of cave diving for about a decade but was getting back into it. Anyway, he arranged a meeting with Hamilton right at the beginning of the project. So Bill came in and cut us a custom set of tables and off we went.

I know that was a blow to you when Parker had his accident. What happened?

It was a few years after Wakulla, and Parker had continued to perfect his cave diving skills. The best we could ever tell was that the sand and rock slope above the opening at Indian Springs began to avalanche during their dive. So it closed the small hole they would normally have come through. On the way out, he and Bill Gavin found nothing. They just saw their line going into sand and rock. From there it’s really sketchy as to what happened. Bill somehow made it through only to find that Parker had already made it through but had drowned just a few feet shy of getting to some extra bottles.

What about Wakulla II?

That was like the next generation. The gear had made quantum leaps. We had the rebreather working well, and Bill just thought it was time to take the next step. Wakulla II represented the future of what was possible. Like Wakulla I, this project marked the beginning of a new world of possibilities. The centerpiece of the project was a fully operational saturation diving rig brought in from the oil fields. With his usual inventive flair, Bill engineered a way to make it all work in the confines of the spring. For the first time ever, divers were doing four and five hours at 90 m/300 ft depths on rebreathers without a care in the world. It was really incredible. After a dive, the team would simply enter a lockout capsule on the bottom, and then be transported to the surface habitat. Using this concept, divers in the future will be able to perform a week’s worth of exploration and only decompress once. Another very exciting development was the 3D mapper Dr. Bill Stone and Barbara Am Ende invented and proved during the project. For the first time, we had true representations of the places we explored instead of the crude stick maps I’m famous for.

What about the WKPP? What’s up with them?

Well, I doubt most of your readers know who they are, but they are the Woodville Karst Plain Project. They’re a highly disciplined group of cave divers who have made a career out of exploring mostly one major cave system. In doing so, they have become the best at doing a certain type of hybrid technical deep cave diving. I really don’t think that anyone’s done it better than those guys. They’re quite extraordinary.

Unfortunately, their current leader, who speaks for the group, is George Irvine. I’ve dealt with his type lots when I was in junior high school, ya know, the schoolyard bully. He likes to pick on—and attempt to demoralize—anyone who doesn’t follow his rules and conventions. Basically, he’s a real dick, a total asshole. The way I look at it is that people like him tend to come and go from this sport. One day, the cave diving community will wake up and he’ll be gone, maybe on to another sport to pick on.

The rest of the core of the WKPP has some really talented guys. They’ll probably always have an elitist type of attitude that they are better than anyone else, but I guess that’s okay. So, I wait with my fingers crossed that those guys who are truly leading the WKPP will one day step up, take the helm, and bring their group, technology, and incredible knowledge and experience into the community as a partnership where they can be functional. But until they do that, they’re kind of a group on their own, is my attitude.

Does cave diving make people antagonists? You’ve got the WKPP and then all the infighting between the National Association of Cave Divers (NACD) and the National Speleological Society-Cave Diving Section (NSS-CDS). What’s up with all that?

I think a lot of it is perception. People naturally congregate in different groups. The NACD and NSS-CDS offer different things, so naturally you get different personalities. But the leaders of those groups get along. I know what you’re talking about, but I really don’t think it’s real. Like I said, a lot of it is perception.

What about the Mike Madden/Steve Gerrard battle that’s been waged in Mexico’s cave system? That’s definitely real.

Yeah, but that’s what happens. That’s a good example. Those were individuals who were in different groups. It’s really between those two guys rather than the organizations themselves. The hearts of those organizations are dedicated to great things: education, conservations, protection of the environment, and outreach.

On a more positive note, tell us about the accomplishments in Mexico at the Dos Ojos and Nohoch Nachich cave systems.

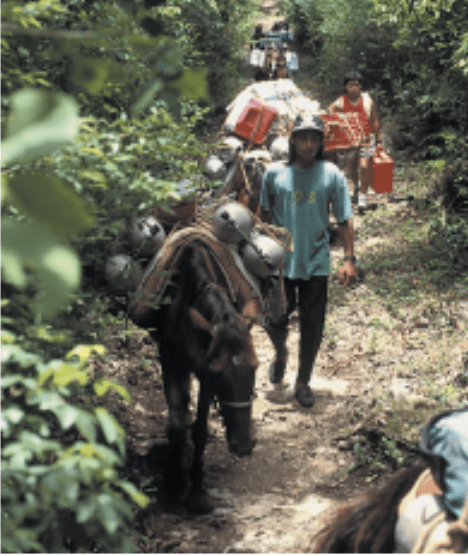

First of all, it’s just a fascinating wonderland down there. I mean, we’re able to do some big-time swims, some 5.5 km/18,000 ft penetrations where we’re blending filmmaking with exploration. Plus, I was fortunate enough to be part of the team that ultimately connected Nohoch to the ocean. And then a couple of years later, it was time to do the IMAX film. We were scouting locations and had the challenge of unbelievable logistics of pulling off an IMAX film in an underwater cave in a jungle. So, we had a very tough decision. I was like, “We have to do it in Nohoch to work with Mike Madden and everything.” But the logistics just forbade it. There was no way we could helicopter everything in. There was no road in there at the time, and I had to face the reality that this Dos Ojos cave was better. And as I did that, I recognized that it was a great cave. I really started falling in love with Dos Ojos.

Has there been much competition between the caving groups to keep pushing further and further in order to make “their” cave the longest?

Oh yeah. Back in 1996 and before, there were lots of exploration competitions going on. Dos Ojos and Nohoch were at the peak of their potential connection, and there were bands of cave divers working projects simultaneously just mere yards from each other in underwater distances but thousands and thousands of feet from the nearest entrances. The competition was fierce, and the goals of who was going to connect what got pretty heated. It was at its lowest point when the Mexican military was out hunting Mike Madden with guns and they had us cornered in one of the holes on the Ejido property. We were there, I guess I’ll say, improperly. We were informed that they were going to arrest us when we came out of the woods, so our determination was to just stay in the woods. So we stayed in there for like 10 days, eking out every scrap of food we had, and kept on diving. When we finally came out, there was no one there to arrest us, so I guess we just outlasted them. But eventually, all of that settled down, and we were able to laugh about it.

Being so close to one another, are Nohoch NaChich and Dos Ojos similar?

No, they’re remarkably different for being geologically so similar. There’s no doubt they’re related somehow or another, but they appear to be within their own regime. So the big-picture geology that sort of controls how caves are formed and the past water level stands all made similar structured caves. Their orientations and their patterns are all laid out side by side. But their differences are quite remarkable in what must be the chemistry of the water in the two caves and, therefore, their appearance.

So what are those remarkable differences?

Nohoch is a much more consistently white, very cleanly laid out cave, and Dos Ojos has a lot more mineralization, darkness in color and black walls in places, and speleothems that are various colors. Both are amazing in their own way, and when you dive both systems you go, “Yeah, this is cool.” I mean, you could drop me blindfolded into either system, and even though most people wouldn’t know, I could immediately tell which cave I was in.

Aren’t they both competing to be the world’s longest caves?

They were, back and forth, Guinness World Records longest caves. I think Nohoch held it the longest just because Mike and his team were diligent about pushing farther and farther and keeping it in the record books. But they still have not been connected yet. They still remain spitting distance from each other, but not connected. Hope’s not given up. It’s funny. Here recently, a lot of us joined together. It’s kind of like two bands, like Bad Company and Foreigner, breaking up and then reforming a new group. Paul and Jill Heinerth were on a lot of the big pushes on Dos Ojos along with Gary and Kay Walton, and since then some of our Nohoch crowd has started diving with those guys. Buddy Quattlebaum put on a trip recently where we all went out there to Pet Cemetery to look at the possibilities of taking what was left of the two old teams and giving it one more whack at making the connection between the two systems.

Pet Cemetery?

That’s one of the territorial entrances of the two cave systems. Actually it is a dry connection of the two caves. But it’s not a real cemetery. I guess it just has that appearance.

Then you were down there again in 1998 and 1999 doing the IMAX with Howard Hall, right?

Correct. Yeah, I was surprised to read that Howard thought I would be threatened to have him coming in. I really didn’t think that at all. Sure, I will concede that I was disappointed when I heard he would be filming because I believed cave divers would be the best people to film underwater cave environments, and there I had the advantage. But as far as Howard’s expertise and knowledge as an IMAX cameraman, there was no question that we were getting a dream team: to have me in control of directing and lighting theI can only say great things about the relationships that were formed when we got down there and how things laid out. It was an amazing team project and quite funny at times. And it was mind-boggling as far as the logistics and technology required to get 18,000 watts of permanent light into the cave and to develop the illusion of cave exploration and discovery with such huge cameras that are so light hungry.

Were you satisfied with the film?

I was thrilled, sort of. I think it’s a great film, but as a purist, there are always things that you see. I would have liked to see the cave-diving segment longer, and I remember a lot of scenes that we shot that must have been awfully good that they rejected to go after the more glorified elements of the film. But, all in all, I was very pleased. It was a difficult but great team effort, and I’m glad Howard enjoyed my serenading him so much.

Let’s jump backwards in time to the film you made with Grateful Dead drummer Bill Kreutzmann. How’d you land that gig?

That evolved from one of the great women divers in our sport, Marjorie Bank. She and I were best friends and she called me one day and said, “Wes, have you ever heard of the Grateful Dead?” And, I just laughed. This was 1991, basically at the peak of their career, and she’d never heard of them. I couldn’t believe it. And she asks me what she should wear. She says, “I’m going to their concert and there’s this guy, Bruce Hornsby, coming to pick me up.” And, I’m like, “Bruce Hornsby is coming to pick you up?” And she says, “Yeah, he’s one of the players.” So I say, “The keyboard player?” And she goes, “Yeah, I think that’s it.” So I’m just sitting there aghast that Marjorie is going to a Grateful Dead concert because she and the Dead are like oil and water.

So I came to find out that she and Billy Kreutzmann had been on a liveaboard together, and they had this run-in at the beginning of the trip about who would get the nicest cabin. Finally it settled out, and Marjorie determined that this guy was just a “lovely fellow.” But that’s the way she was. So, we were coming back from the Underwater Canada show, and she asked me to come to Atlanta with her to see the Dead. We went straight in with our backstage passes and we met Jerry and Billy and Bobby and Phil and the whole group. And, of course, Jerry and Bob and Bill were all big into scuba diving. They had already seen a bunch of my films so they were like, “Tell us about this and what about that.” So Billy came down to High Springs about two weeks later with some Betacam gear and wanted me to show him how to use it.

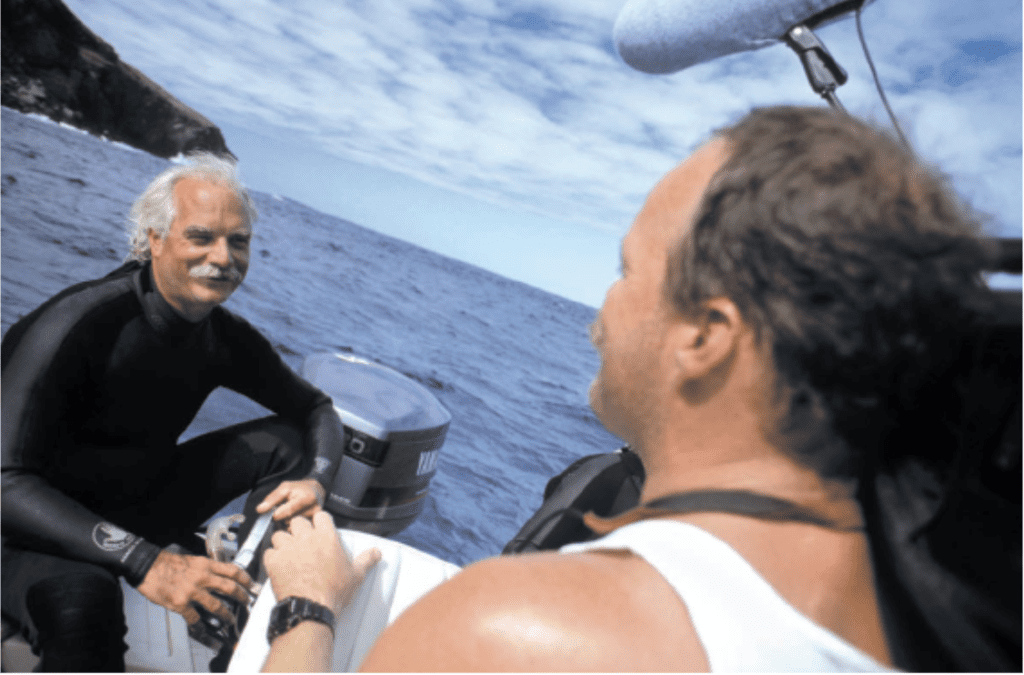

After a couple days of playing around with the camera in the springs he says, “I’m not really getting this, am I?” And I said, “Hey, you don’t just grab this stuff and start using it. It’s taken me 18 years to get halfway competent, and you don’t just learn it in two or three days.” So he goes, “Well, why don’t you come with me on this expedition. I’m going to take a sailboat 2,897 km/1,800 miles from San Francisco down to these islands, the Revillagigedos.” So we jumped on this sailboat in San Francisco on what would become an epic journey.

And what was the goal of the expedition?

It was really about exploration in the spirit of cave diving but to go down and document and map and tell a story of the Sea of Cortez— stopping in fishing villages and meeting people and checking out marine life and filming and ultimately heading down to this group of islands which have now become very popular. But back then, hardly anybody had been there. So we dove Socorro and Benedicto and updated maps and drawings . . .

And taking a little LSD on the side?

No, [laughing] no LSD on that trip!

What was the film called and how did it play?

It was called Ocean Spirit, and it was received extremely well and was a well-done film. It’s a very different kind of film.

How do we get a copy?

I think it’s available on the Grateful Dead website.

Let’s jump into gear. Are rebreathers passing us by? Are we relegated to cylinders until the end of time or will Joe Diver ever use a rebreather?

I believe we’re marching quickly toward the ultimate evolution of rebreathers entering the diving market. I know people don’t see it that way, but it’s coming. From my point of view, having been one of the first guys to ever dive a rebreather in a cave environment, they are now commonplace here. I mean, people are diving Megladons and Cis-Lunars. You see Buddy Inspirations and all kinds of incarnations in between. It’s just a lot more prevalent. Photographers like Tom Campbell are diving rebreathers and filming in high def. Howard Hall is doing it, and I’m doing it. We’re out there on the cutting edge in open water and technical environments using this technology. As history shows, when we do it, it becomes a permanent part of the sport.

Sheck and a small band of people decided to drill some holes in the first stage of a regulator. Back when I was a kid, I would go into this machine shop in Jacksonville, and I would see chrome shaved off of regulator housings down to the brass. Joseph Califino, who was this old machinist, would be drilling holes in regulators where holes had never been and tapping in new hoses. We now all dive with octopuses and safe seconds and inflators. Those things were developments out of the need for more efficiency and more safety in cave diving that ultimately became a permanent part of diving equipment.

The Stabilizing Jacket, what is now the common design for buoyancy, came from Court Smith and me mixing buoyancy compensators and inner tubes and horse collars together and creating things that became a permanent part of better diving. So, I think it’s at that point now with rebreathers. They’re permeating all levels, and one day we’ll have hybrids. I think that’s where we’re headed, toward some hybrid like cars are going now. They still use gasoline, but they also have battery power. I think we’re going to find ourselves diving semi-closed rebreathers that are packed down so we’re not diving 80s or 72s anymore. We’ll be diving 30s or 40s and getting four or five times longer than a single tank allows us to dive. It’s all good.

Except for Dräger’s sporadic support, none of the mainstream manufacturers have embraced rebreathers. Why do you think that’s so?

I think it hasn’t gotten there economically and ergonomically yet. People are still putting them together with plumbing supplies and PVC, and they’re still garage-built things. What’s going to happen is that one manufacturer will get a foothold firmly enough that the money will come and they’ll overcome the liabilities and step into the big time. And that’s forthcoming.

Do you see any other major gear developments coming down the pipe?

From a photography point of view, certainly digital image making and high definition. I’m right there now working on these hybrid projects for National Geographic. We’re now using digital image making in the pages of the magazine.

Digital still cameras?

Yeah. And I did the first ever all-digital presentation to the National Geographic editors. It was the first time a slide projector was not in the room showing images for a final presentation. Up until that point all the presentations had gone, “ka-plunk, ka-plunk, ka-plunk.” And they all stopped and turned around and went, “Have we ever done this before?” And they all said, “No.” And then they said, “Well this is a first. I guess we’re going into the new millennium with this.” And one of ‘em said, “It better be good, Skiles.”

It was a presentation on Antarctica, and I did it all with my laptop and a projector and showed scans and frame grabs from three different formats: from regular traditional still photography with emulsion, from digital photography, and then from actual frame grabs off my high def camera. This evolution is leading to a sort of hybrid world in which you can grab publishable photographs from motion picture frames, and we’ll be seeing more developments along the lines of digital matrix photography, which starts to truly compete with film emulsions. And when that happens, that’s another evolutionary step for our sport because it just opens up a world of possibilities.

Are you still shooting with still film?

Yeah, I’m going out this weekend and shooting with 70mm, 2 x 2 stuff. I still love the old traditional quality you get with film, but there’s nothing like the quick feedback that digital photography gives you.

How do high def and IMAX cross? Are they two different graphs, or do the lines cross somewhere?

Well, I think the lines will eventually cross and maybe trip each other up at the same time. There’s a lot happening very quickly in the world of high def, and the most prominent area of high def crossing over to IMAX is in the use of this equipment in 3D. They take two high def cameras, stereo them together, and shoot what is truly high def, IMAX-quality 3D film by doubling up on the images of two high def cameras. When you put just a single high def camera in the housing and say, “This is shooting the same as 70mm film is shooting,” that’s just a joke. There’s no way that it’s there yet. It’s the same as saying that the best digital still camera is shooting as good or better than film. It’s not there yet, but it doesn’t have to be.

We’re going in the wrong direction. We’re asking digital to become film. But what digital does much better than film is its own thing— digital. It should be kept in the digital domain and projected digitally. So, what I think we’re going to see is this split personality battle. I think we’re going to see high def theatres. We’ll see what I call Digital IMAX theatres that can be built in half the size and a tenth the money. They’ll give people similar experiences—the big images, the surround sound, the big action—so that now they’ll be in museums and aquariums and special education outreach facilities and theme parks can have very specialized films. This is an area I’m very excited to be working in. I’ve just gotten a major contract with the State of Florida with the Department of Environmental Protection to create the first even high def film on the Florida aquifer and the explorations inside the springs and caves to help share with the world the value of those resources. Initially, we’re building a Welcome Center in Ichetucknee Springs State Park which will show it in high def with 6.1 surround sound. Ultimately, we hope this will be the flagship model for other facilities in Florida.

Stepping back, how did the whole digital presentation on Antarctica go?

I got the hair-brained idea to go to Antarctica with some suggestions from Emory Kristoff. He told me that he knew about a ship that was going down there, and that National Geographic wanted to hear a new idea from me, so he thought I should go down. It was already one of my goals, because I had always wanted to go down into that hostile environment and try out some state-of-the-art technology. So I went up to Washington, D.C. to give a presentation. And the night before, Emory told me that I hadn’t told him anything convincing. He said, “This thing better be good or you’re dead meat.” I was like, “Thanks Emory.” And so I attempted to go to bed and really didn’t have a strong story idea.

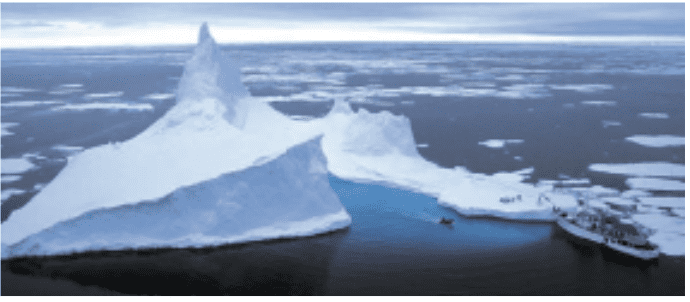

So, I decided to browse around on the Internet and stumbled on the fact that just two days prior to the meeting, the world’s largest iceberg had broken off of the Ross Ice Shelf. I logged on and got into the conversation between two guys, Dr. Doug McAyeal and Matthew Lazarra, and they were talking about what was going on from their different disciplines. And I’m thinking, “This is it.” So, I pinged those guys and asked them a little about it and went in the next day and said, “We’re going to go to the largest iceberg in recorded history and we’re going to go diving inside of it.” [Ed. note: The B-15 has now been superseded by A-76 Iceberg]

And that did it. So from that point on, we put together a program to take rebreathers, high definition equipment, and a vessel capable of getting us there with a helicopter on the deck so that we could navigate, shoot aerials, and explore that world. About eight months later, we were off. We set ourselves up for what would certainly become one of the most difficult expeditions in modern time. We left from Wellington, New Zealand on a 37 m/120 ft boat with a 3,862 km/2,400 mile one-way journey just to get there. We crossed what is the most violent sea on the planet, the Southern Ocean. On about the sixth day into the trip, we hit 12 m/40 ft to 15 m/50 ft seas, and I just got battered for days on end. When we battled through that, at one point, we rolled and thought we weren’t going to come up. It was getting pretty ugly. We finally got a break in the weather and then got caught in a Katabatic storm, which is like a hurricane-force storm.

So, we hid behind icebergs to get away from that, then we got trapped in the pack ice, and we’re all just trying to get near this iceberg. It was one thing after another that kept knocking us back. We finally decided we weren’t going to make it to the iceberg, and we retreated a little bit after being trapped in the pack ice for about five days. We set up base camp on an iceberg and got our wits about us and decided to give it one more try. During that time, we were doing our forays into the water with our rebreathers and the rest of the equipment. And ultimately, we still fell shy of getting to the iceberg. Finally the helicopter pilot—Laurie Prouting, a really amazing New Zealand bloke—and I hatched this hair-brained plan to fly the helicopter, hop-skipping it across icebergs and carrying in extra fuel on the skids and camping gear and physically flying to B-15. And that’s what we did. We flew there and were the first human beings to land on the largest iceberg in recorded history, and we planted the flag. There’s nothing to prepare you for the magnitude and the immensity of it.

So how big is it?

It’s huge, 274 km/170 miles by 64 km/40 miles. It’s about the size of Jamaica. And it’s 671 m/2,200 ft thick on average, so it’s 610 m/2,000 ft deep under this thing, since 10 percent of an iceberg sticks out of the water.

What else did you learn about it, besides the fact that it was really big?

The science we learned was quite remarkable. Through aerial photography and a few basic studies that we were given by the scientists on our ship, we were able to document some really profound things about the way B-15 was impacting the entire Ross Sea. Eventually, we returned to the ship, we retreated from that area to find a new area of icebergs, and we started diving inside the caves. It was ethereal to go inside the ice caves. Again, I’m with Jill and Paul Heinerth—who were remarkable divers on this thing—pioneering the use of Cis-Lunar rebreathers and using this technology to dive further and longer than any human being had ever done.

Where did you go after you left B-15?

We went around to a place called Cape Hallet on the mainland, which is a little tamer, and we found a group of really nice icebergs to explore.

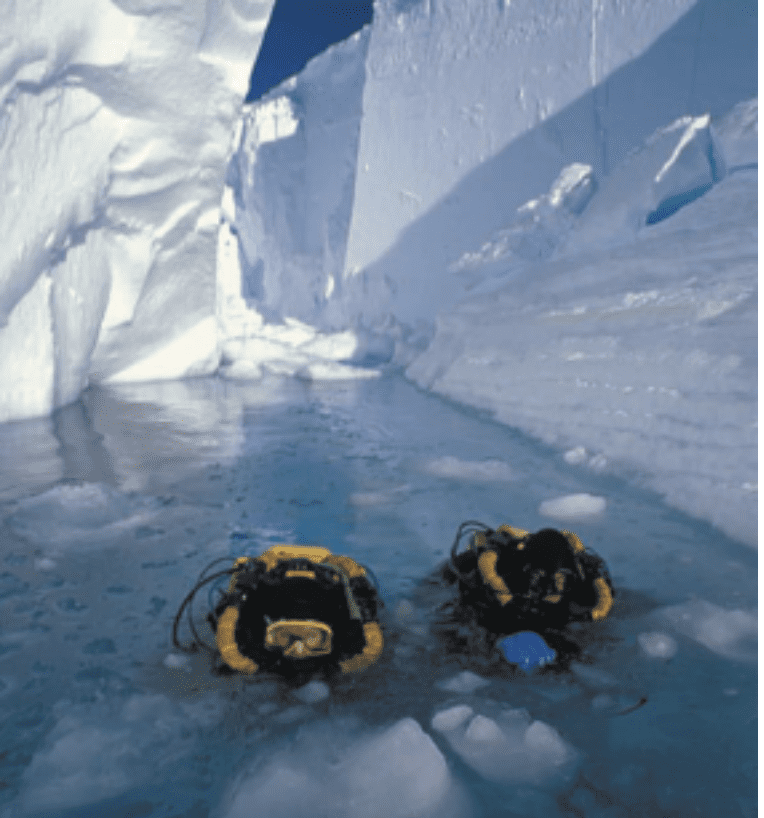

How did you find the caves?

We started probing around and boating around. Basically, we looked for caves like we would look for springs in Florida. We would systematically start exploring icebergs. We’d fly around and say, “Hey, there’s an iceberg that looks like it has geology.” Or I guess you’d call it iceology. And we’d find cracks and folds in the ice. Finally we found a place that had a huge crevasse in it. I wanted to film the first-ever attempt from above water and make sure that Paul and Jill took underwater cameras with them. So they entered the crevasse, and while they were in there, I was left in the boat. All of a sudden, there was this gut-wrenching sound, and this chunk of ice about the size of a house turned, and our boat got thrown about 5 m/18 feet into the air. We came down, almost tipped over, looked down, and the crevasse was gone.

From our vantage, it was closed. Sealed completely with them trapped inside. For the next 45 minutes, we backed out of this thing because it was continuing to fall apart. We realized right then how unstable these environments were. The whole time we were thinking that Paul and Jill had been killed. Then they showed back up somewhere else. They hadn’t experienced what we had and didn’t even realize anything had happened.

After we got over that incident, we went back and continued exploring farther and farther back into these caves. We were using Oceanic drysuits, Patco suit heaters, and the rebreathers with their warmer air, so we were able to stay down much longer than people can normally stay in those kinds of waters. You’ve got to remember this water is -2.2 °C/28°F, only a tenth of a degree from turning into ice. We finally reached a point where we were 305 m/1,000 ft inside this cave, which we called Ice Island Cave Number 4. Suddenly, we found ourselves in a violent current situation which was totally unexpected. We started trying to swim out and were making no progress. The thing that was holding me back was the high definition camera, and I was like, “I’m going to die before I drop this camera.”

The rebreathers were really getting taxed. By the way, we had tried to do some open circuit stuff before, and every time it failed miserably. Anyway, so there we were, down at 40 m/130 ft inside of an iceberg being pulled in by a siphon current. We were at 82 minutes, and I remember thinking that we were really deep in shit.. Luckily, we were able to persevere. Paul got alongside me, and we found some areas where the current wasn’t so strong, and somehow we were able to work our way out. When we reached the entrance, we had a lot of decompression but not nearly as much as if we had been on open circuit. During decompression, I realized that Bill Stone’s Cis-Lunar rebreather had kept us alive in what would have been unsurvivable conditions otherwise.

Sounds like Antarctica was one helluva trip.

Yeah, it was. We had the hellacious crossing and several near-death experiences. But overall, it was another incredible adventure. The film is called Ice Island and will be released on PBS later in 2002. You can get copies through my company, Karst Productions.

What are some of the other more memorable projects you’ve worked on?

Well, several other projects immediately come to mind, largely because of the drama that unfolded on each. The first was the expedition to Nullarbor in Australia. It was during that expedition that a freak storm collapsed a massive cave entrance. Thirteen unlucky individuals, including myself, were buried underground. It was one of the most horrifying experiences you could ever imagine. Fortunately, we were able to escape to a chamber where we were able to regroup. Over the next two days, Dirks Stoffels, the late Rob Palmer, and I explored our way partially out of the cave. We were literally crawling and climbing in places where solid walls had existed just hours before. Miraculously, a friend and fellow caver, Vicki Bonwick, had managed to explore down from the surface and we met her on an unstable ledge somewhere in the middle of the new cave. Everyone managed to escape unharmed, but I lost a vast quantity of filming equipment.

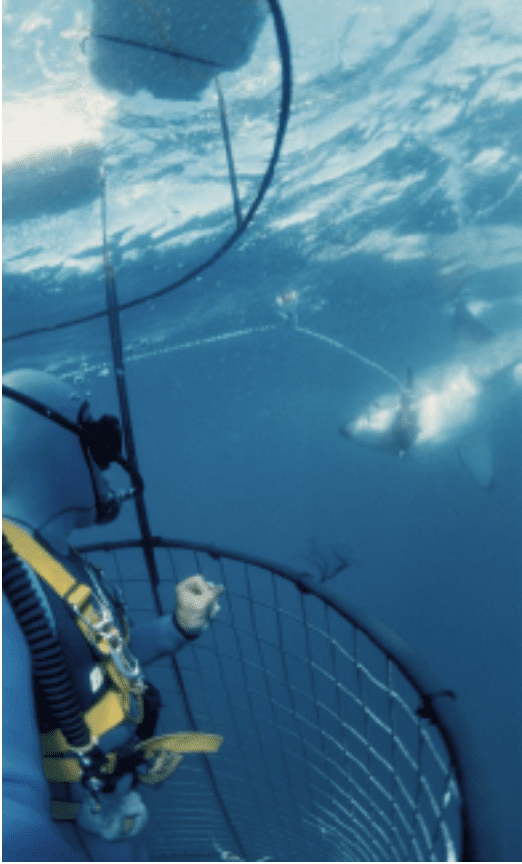

The next would be trips I made to South Africa to film White sharks. No one had really started working there yet, so I built some really poor shark cages and literally hitch-hiked around from bay to bay exploring and filming. I had lost my first cage in a really violent storm, so I built another that I thought would allow me more freedom to get really good shots of pointers without the cage. It ended up almost being my undoing. On one particular pass, a 14-foot female hit the cage just right and it pried open like a Gary Larson cartoon.

The shark literally crashed into me and began to seriously thrash me. My only defense was my 16mm film camera, and it was a really good thing I had it. I kept screaming, “This is it, this is it.” If you ever wonder what you might say when you think you’re really going down, that might be it. The shark swam us deep before it came to the end of the rope tied to the boat. When we stopped, the shark stopped struggling for a second and the foam blocks pulled us to the surface. For the people in the boat it was evidently an eerie and frightening sight seeing this massive tail rise up out of the water. When that happened, the shark’s position changed, and I started pushing it away from me with my camera. As fast as it had happened, the shark popped out of the cage and swam off. When I surfaced, one of the crew threw up on me because they thought I had been eaten.

Deciding I should leave that type of filmmaking up to Howard Hall, I retreated back to caves and joined up with my old friend Bill Stone for what would become one of the most extreme descents into the earth ever attempted. The place is called Huatatla in Southern Mexico and is poised to be the deepest cave on earth. I went down there to photograph it for National Geographic. I arrived to the news that a good friend of mine, Ian Roland, was dead. He died at 1,353 m/4,439 ft beneath the surface. A week later, after we got Ian out, Sheck Exley drowned on his depth record attempt in Northern Mexico. It was an extremely tough time in my life. Not only did I feel like I had been playing dodgeball with the Grim Reaper, but now all of my friends were getting taken out—unable to dodge the ball in the ultimate game of life on the edge. To make matters worse, a week later I found myself trapped again, this time by floodwaters that came without warning. We were trapped for five days with no possible rescue or help from above. When the floodwaters finally receded, I decided I’d had enough. It took me eighteen hours to ascend on rope out of the cave system. On the surface, life never had seemed so beautiful.

What else is in store for you in the near or distant future?

Surviving is pretty much on the top of my list, but I plan on continuing to do what I have always done, which is to pursue adventures in exploration and filmmaking. It’s a nice combination for me. I hope to continue to help encourage and advance technological tools to allow us to trek into the unknown and make images along the way. I would also really love to see the rebreather and one-atmosphere diving concepts reach their prime during my tenure as an explorer. With that in mind, I would like to think there are some more unimaginable projects out there for our team to crack.

To explore more stories, documentaries, videos and articles by and about Wes Skiles click here: Celebrating Wes Skiles

Fred Garth is a wily veteran of the adventure sports media industry. He launched Scuba Times Magazine in 1986 and went on to help craft 13 more magazines, notably Fathoms, DeepTech Journal and most recently, Guy Harvey Magazine. During his career he has worked with media giants from CNN to National Geographic to the New York Times.

An avid diver, Garth worked his way up to rebreather instructor and has scuba dived in nearly every ocean. As a longtime leader in the ocean community, he has collaborated with influencers and explorers such as Jacques Cousteau and his son Jean-Michel, as well as Dr. Sylvia Earle, Dr. Bob Ballard and Dr. Guy Harvey.

These days Garth dives, fishes, travels and still writes about it. He and hIs wife have survived 30 years of marriage and raised two daughters aged 21 and 26. They split time between hanging out on Perdido Key, Florida and Crested Butte, Colorado.

Bret Gilliam has been professionally involved in the diving industry since 1971, a career now spanning over 50 years. Since beginning diving in 1959, he has logged over 19,000 dives around the world. His background includes scientific expeditions, military/commercial projects, operating hyperbaric diving treatment facilities, liveaboard dive vessels and luxury yachts, retail dive store & Caribbean resort operation and ownership, as well as filming projects for movies, television series, and documentaries. He was founder and President of six multi-national diving companies including V. I. Divers Ltd., AMF Yacht Charters, Ocean Quest Cruise Line, TDI/SDI, UWATEC, DiveSafe Insurance, and four diving magazines. He is President of the consulting corporation, OCEAN TECH, since founding that company in 1971.