Cave

Wesley C. Skiles: Extreme Cool

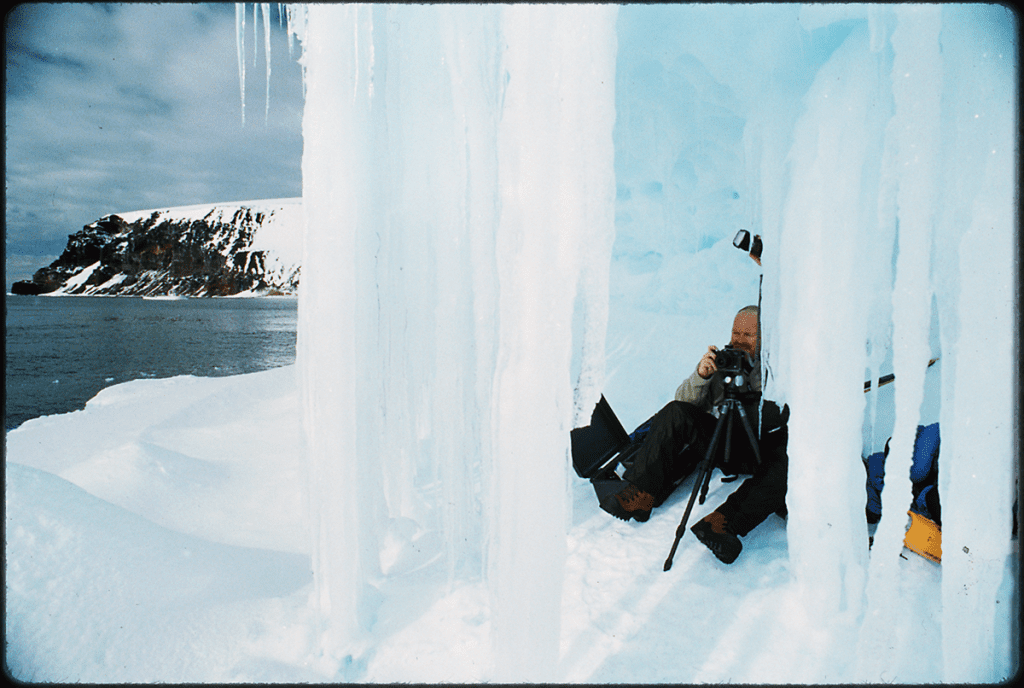

By Emory Kristof. Header image of the B-15 iceberg by Wes Skiles appeared in National Geographic “Islands of Ice” in December, 2001.

I first learned about Wes Skiles when watching a documentary about a group of divers trapped underground in Australia. It seemed that a sudden heavy rainstorm started filling up the cave system the divers were exploring. In the center of this developing tragedy was Wes. Through a display of extreme cool, MacGyver-like problem solving, super diving technique, and just maybe a little bit of luck, there was a happy ending, with all the rescued mud-soaked divers wrapped in blankets and looking like drowned rats, but grinning happily in the late afternoon sunshine. Wes had the biggest grin and the best quotes. “He was the man,” and I was looking forward to meeting him and working with him someday.

We met at Wakulla Springs, Florida, for planning meetings for a large project to explore the Springs with scuba, underwater habitats, powered scooters, and the ROVS I could bring from the Geographic. Wes was impressive in person. He was a legendary cave diver and explorer of the freshwater cave systems of Florida and Mexico. He could organize and lead anything. But it was the awesome beauty of these dark and little-known watery realms that Wes wanted to bring to us surface dwellers. Wes knew, loved, and understood the importance of the hidden Karst formations, and he felt it was necessary that we were educated and cared, too.

Fresh water is taken for granted, and wasted, by most of us. Wes went to the underground sources of much of this underappreciated resource, and crafted magnificent images unlike any I had seen before. These pictures, whether still or motion, were “stoppers” that could hold your interest and make you curious to find out what they were about. Then Wes had you, because he was a great storyteller and educator, and a single drop of water traveling under a Florida city was on an important mission. Wes learned to master many skills to feed his passion, but his core skill had to be that of “Jedi” Diver. There are many levels of scuba diving expertise, but cave diving at the level at which Wes was engaged was in a class all its own. It is ironic then that Wes’s last dive was not in a cave, but in 60 feet/18m of open water doing a science dive off the coast of Florida.

Wes was a great guy to share an adventure with in the field. As hard as Wes worked, he also liked to laugh and make music, mostly on his harmonica. There are fond memories of Wes in a NewtSuit surrounded by Six Gill sharks at 600 feet off Vancouver Island. Wes was making a TV show entitled “Walking With Sharks.” I was filming from Phil Nuytten’s Otter submersible. One of the sharks went cruising between Wes’s legs, giving him a thrill. I told him we had hung a pork chop between his legs before we launched him. He was speechless for the first time I can remember.

Wes and his friend Jeffrey Haupt went out to Rongelap in the Marshall Islands with Teddy Tucker, Bill Curtsinger, Eric Hiner, Mike Cole, the owners and crew of the 85 foot Yacht, MYSTIQUE, and me to do the Magazine Story and TV show on the animal life up to one mile deep in the waters surrounding the Rongelap Islands. Rongelap was 70 miles from Bikini Atoll and had been covered by three inches of radioactive fallout from the largest H-Bomb the US ever tested in the 1950’s. The population had been evacuated AFTER the test.

At the time of our visit, everything alive on the islands was still radioactive with Cesium 137. The fish life was thriving, the water was clean, but nobody could live on the land. Every evening after dinner we sat on the after deck of MYSTIQUE and had a concert by Wes on harmonica and Jeffrey on guitar. It was surreal to listen to Wes’s mournful blues offshore of this radioactive tropical paradise with its rotting little church and swarms of flies. We felt like the last survivors at the end of the earth.

In the Mexican Yucatan, Wes was part of a large group of archeologists surveying a major new Maya Cenote site. I had a smaller group, with a pair of small ROVS, taking a quick look at some of the surrounding smaller sites. We would all get together sometimes at lunch and late in the day to compare notes. One day after lunch, Wes had an urgent case of the Mexican two-step. He grabbed a roll of toilet paper and went running for the jungle with the TP held over his head and streaming in the wind, all the while screaming like a banshee. Wes really knew how to liven up a dull meeting. I will never forget the image.

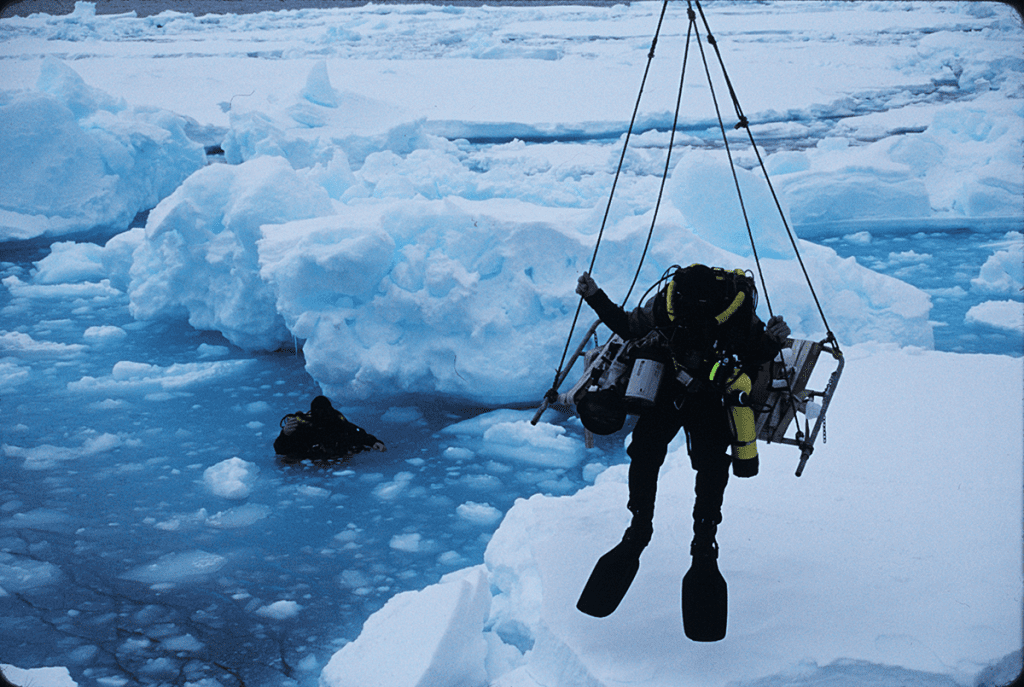

All of Wes’s stories in National Geographic were special, as were his TV shows. I was pleased to help him fund and produce his Antarctic adventure on the large B-15 Iceberg. Wes mentioned our getting together on another project after he finished his Blue Holes story for National Geographic Magazine. This was the cover story for the August 2010 Geographic, and it is a great piece of work that everybody at Geographic is very proud of, but it is carried by Wes’s images. Wes was the greatest, but he left the scene too early, leaving us all wanting more Wes. His family, friends, Geographic Editors, and his diving buddies all will miss him dearly. I hope the angels appreciate harmonica music.

To explore more stories, documentaries, videos and articles by and about Wes Skiles click here: Celebrating Wes Skiles

The National Geographic Magazine has been doing stories in the deep sea since William Beebe went *One Half-Mile Down” in 1934. The discovery of new life forms around volcanic vents, huge deep-dwelling sharks a mile down, shipwrecks such as the TITANIC, BISMARCK, and EDMUND FITZGERALD have been covered by Emory Kristof in the pages, videos, and IMAX of the National Geographic.

For over 60 years, Emory has grown up with the developing submersibles, and remotely operated vehicles (ROVS) that helped him produce the images he wants to share, excite, and educate people about the deep sea.