Education

Why Expert Divers Might Not Make The Best Instructors. What You Can Do To Improve Your Teaching

Experts and those with in depth experience tend to have very different decision-making processes, making it harder for students to learn from them than from newer instructors and intermediate divers. The key for pros, explains human factors coach Gareth Lock, is focusing on specific elements of their process. That’s where a robust, structured debrief can help!

by Gareth Lock

All images courtesy of Gareth Lock unless otherwise noted

We’d like to think that we could learn from the best divers out there, the explorers, the world-class photographers, or those with thousands of dives under their belt. Often, there is an opportunity to learn from these divers, but only if they can explain how they make their decisions that lead to actions, and this isn’t easy, especially if they don’t understand the different internal processes that novices and experts go through to make effective decisions. I know it is something I struggle with sometimes, and I teach this stuff!

This article will explain how a key internal decision-making process works and why both novice as well as intermediate-skilled divers need different information sets to expert divers. The majority of this article is based on two pieces of work: Dreyfus and Dreyfus from the early to mid-1980s who looked at how learners acquire skills through formal instruction and practice, and Klein who looked at how those in high-performance, time-critical situations made decisions such as fire chiefs or operational military commanders.

The article will close with how you can improve your instruction by focusing on certain elements of the decision-making process rather than just looking at the outcomes.

Learning and Improving

The goal of a diver education programme should be to prepare students to dive in the real world with a new set of skills and knowledge e.g., GUE Fundamentals, Tech 1, Cave 1, or maybe to operate a new piece of equipment like a rebreather with CCR 1 or a DPV. There are training materials provided which focus on giving the students the ‘rules’ to follow during an activity. This could be gas planning, sequencing of motor skills (back-kick, shutdowns, or bailout) and team protocols (gas sharing, signalling during an ascent).

There are performance metrics associated with each of these skills, and these metrics allow the instructor to determine whether the students perform the skills and then pass the class, and they also show the students where the bar is set for passing and then diving in the real world.

These materials and performance metrics also provide the students with the knowledge to meet two of the three basic performance modes we operate in.

- Skills-based performance. This is where a simple pattern is recognised almost subconsciously, like feeling the tension in your ears when descending and then clearing your ears or signalling to a team-mate when you hear bubbling from behind your head. To develop skills, we have to practice many times with correct feedback so that both cognitive and muscle pathways are developed correctly. Correct feedback is needed, otherwise we get very good at doing the wrong thing!

- Rules-based performance. These ‘rules’ are based on what has been taught on the course in particular, and our lives in general. If I sense ‘x’, I do ‘y’ to achieve ‘z’. As we practice the skills associated with the ‘rules’, then we pay less attention to them and they move into skills-based performance. For example, when ascending, the diver would dump ‘some’ gas from their BC, ‘some’ depth below the stop depth to stabilise at the depth. What depth below the stop and how long the OPV is held open is something that comes with experience and isn’t really thought about i.e., rules-based performance has moved to skills-based performance. Another example would be, if you see a light being waved side to side at a fast pace, then you would get ready to deploy your long hose as the diver has a major issue and likely needs gas. Rules aren’t just technical in nature, they are also social and cultural e.g., how to behave around certain people or how hierarchy/authority is respected.

- Knowledge-based performance is the third mode, and this is the space in which experts operate. More of this below.

From Novice to Expert

Dreyfus and Dreyfus developed a framework that showed there were five stages to skills acquisition and development. These stages are shown below, and no doubt you will recognise them as you have developed your own skills.

- Novice: At this stage, there is an incomplete understanding of the task, divers follow through task sequences in a mechanistic, logical manner and will need supervision to complete them successfully. Novices do not see the context, only actions in isolation.

- Advanced Beginner: Here, the diver has moved from single steps under supervision to understanding the steps within the direct context of the dive or diving activity. However, they still need some level of supervision.

- Competent: The diver has both a good working and background knowledge of what they are supposed to do, and they have started to see the links between context, action, and outcomes. They can execute skills independently to a standard that is acceptable, but they may lack finesse.

- Proficient: The diver now sees events and actions as one ‘system’, and they understand the big picture. They can look ahead and plan what needs to happen for simple diving operations and can execute skills to a consistently high standard.

- Expert: These divers have a deep and holistic understanding of the ‘system’ (equipment, environment, people, procedures…) which means that they deal with routine matters intuitively, can ‘see the invisible’ (what things are missing), and can achieve excellence with ease.

The problem can arise when experts try to teach novices or advanced beginners, because the way each of them makes decisions is different. Experts are able to match patterns from what is being sensed because they have a vast array of memories and experiences to relate to, something that novices don’t have. For the novice and advanced beginner, they are trying to match the data against rules, but they don’t have the correct sequence to follow, which means errors are much more likely.

If the novice/advanced beginner comes across a scenario they haven’t seen before—like poor visibility in high current—then they have a number of options, the primary one being to end the dive. However, if social pressures are present making this decision hard to make, then they will continue on the dive, hoping they can resolve their stressors.

A simple analogy would be from the film, “The LEGO Movie” in which booklets are used to build specific LEGO models, but the Master Builder is able to create anything because they know how the pieces go together. The Master Builder also knows what models are needed to solve problems in the future rather than building models because they are there!

Tacit Knowledge

Experts have developed tacit (internalised) knowledge about how to solve a specific problem, and tacit knowledge is some of the hardest knowledge to transfer to others because it is heavily contextual. In effect, the story or understanding is created by collecting the surrounding data and making sense of the gap in the middle (more of this further down). Tacit knowledge is one of the areas I struggle most with when trying to get Human Factors concepts and knowledge across to divers. It is much easier to answer a specific question because the context is there, but a novice or advanced beginner wants to have simple rules to follow. These rules are very difficult to define when it comes to the application of human factors and non-technical skills because we are dealing with people within context, and there are so many different variations possible.

Experts are often criticised for not following the rules (checklists, pre-dive briefs or debriefs), or at least not demonstrating that they are following them. This is not unsurprising given how experts make decisions in real-time. However, it does mean that experts may not be the best role models when they are in ‘expert’ mode.

We should also recognise that being an expert is not the end. There is always a need to keep improving and developing in diving. The diving world continues to evolve with new equipment, new concepts (like human factors!), and new or revised ideas regarding decompression strategies or medical knowledge; and as such, when the external context changes, the expert moves to being a novice or advanced beginner in that space.

Expert Decision Making

Dr. Gary Klein and his associates undertook research in the late 1980s to understand how people made decisions in uncertain situations. Their initial focus was on fire fighters, fire chiefs, and military commanders. All three sets of individuals had to make decisions when time was limited and invariably, when they also did not have all of the information. Despite this, the successful chiefs and commanders had good outcomes on a regular basis, and Klein wanted to understand how this was achieved.

What Klein and his team recognised was that it wasn’t direct, technical skills that led to successful outcomes, but the ability to ‘see the invisible’. Experts were able to do a number of things that novices or intermediate skilled operators weren’t. They were able to make decisions with fewer pieces of information because they were able to infer what might happen next. This meant that decisions could be made much quicker, and when fighting fires or the enemy, then time is of the essence. The novices would look for ‘one more bit of confirmatory evidence,’ but by the time that happened, the decision had been made for them by the clock.

Experts recognised that a decision is better than no decision because the clock will catch you eventually and force your decision. Experts effectively manage the constant tension between “Don’t just do something; stand there” to work out what is going on, and “Don’t just sit there, do something” and reflect/debrief when things didn’t go quite to plan.

What Klein identified was that it was this constant reflection post-task, using formalised and structured debriefs, that allowed the operational teams to improve. They would sit down and talk through what each of them had sensed and perceived as they reflected on the activity, sharing this with others in a psychologically-safe environment. This sharing allowed others to create mental models of what had happened, and why, and what might happen and how to spot the events development. Note, this sharing didn’t just focus on outcomes, but also on the cues and clues leading to the decisions that would be needed. It is this pre-decision-making reflection that creates the tacit knowledge and allows the ‘invisible’ to be spotted. Experts had more patterns to match, which meant that they could run more mental, subconscious simulations about what might happen. They wouldn’t logically work through potential scenarios, they would look for the ‘good enough’ (satisfactory) option given the other constraints they had to deal with and goals they had to meet.

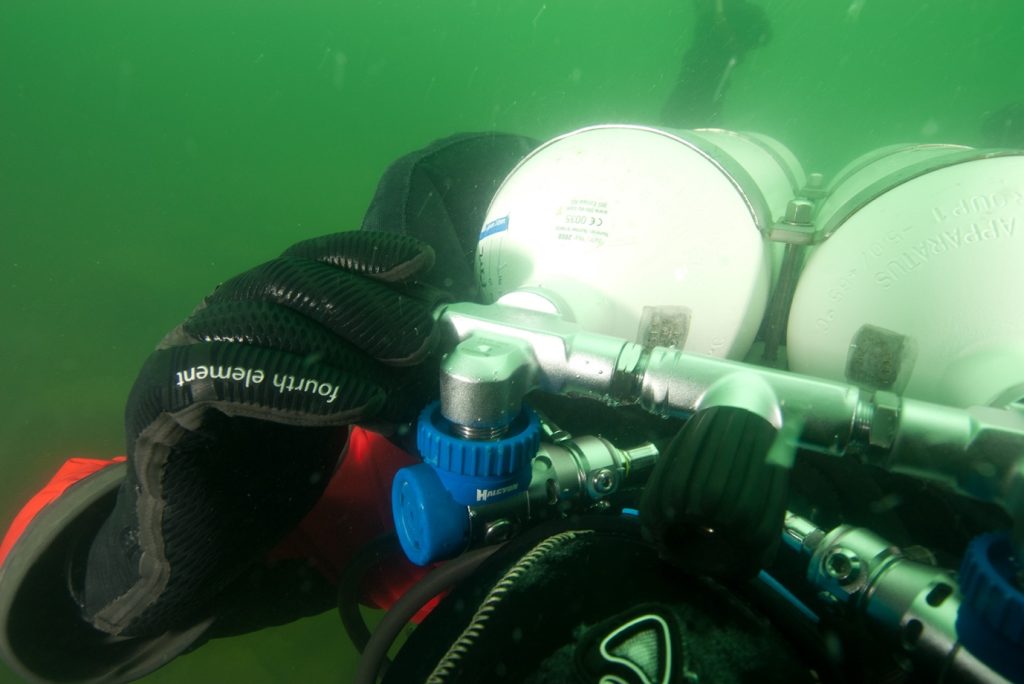

A diving example of pattern matching might occur when, while sitting on a bench on the boat, a diver puts their drysuit feed over the top of their long hose trapping the hose. A novice would potentially miss this because they just see that the drysuit feed is connected (rule) but they don’t see the need to be able to donate gas later on. (This team doesn’t know how to do a GUE EDGE drill which includes the step to deploy the long hose before getting in the water or descending). A proficient, or expert, diver experienced in using primary-donate would notice this situation and say something.

A ‘good’ expert would provide the rules to follow for the other levels of competence or maybe tell a story to identify the cues/clues that could be spotted. A ‘bad’ expert would say something along the lines of ‘pay more attention to potential issues’ since they intuitively know what the potential issues are and make an assumption that the other divers/parties know what the issues are as well.

Debrief – A Key Skill To Learn

Debriefing is a skill we are used to during classes to improve our technical skills, but we are rarely taught how to debrief a dive after a class so that learning can continue. The hardest part of debriefing is looking at WHY something we did went well and HOW to improve those activities which didn’t go so well. Observing or identifying is one thing, identifying the context or behaviours is much harder. This Debrief Guide can help with that learning process.

Conclusion

Decision-making techniques vary between novice and expert. At the novice level, there is an expectation that there are a set of rules and guidelines to follow, and that as long as they are followed in sequence, then there will be a successful outcome. However, as experience and skills develop to the point where they are an ‘expert’, they gradually stop using formal rules and guidelines and rely more on intuitive decision-making based on experience and feedback. The difficulty is that experts are using tacit knowledge to identify the cues and clues around the problem and seeing the ‘invisible’, something that novices struggle with. The easiest way to improve decision-making is to reflect on what you have done using a structured debrief. This isn’t always easy, but it is certainly worth it.

Dive Deeper:

Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society: The Five-Stage Model of Adult Skill Acquisition by Stuart E. Dreyfus

Researchgate.com: A Recognition Primed Decision (RPD) Model of Rapid Decision Making by Gary Klein

Gareth Lock has been involved in high-risk work since 1989. He spent 25 years in the Royal Air Force in a variety of front-line operational, research and development, and systems engineering roles which have given him a unique perspective. In 2005, he started his dive training with GUE and is now an advanced trimix diver (Tech 2) and JJ-CCR Normoxic trimix diver. In 2016, he formed The Human Diver with the goal of bringing his operational, human factors, and systems thinking to diving safety. Since then, he has trained more than 350 people face-to-face around the globe, taught nearly 2,000 people via online programmes, sold more than 4,000 copies of his book Under Pressure: Diving Deeper with Human Factors, and produced “If Only…,” a documentary about a fatal dive told through the lens of Human Factors and A Just Culture. In September 2021, he will be opening the first ever Human Factors in Diving conference. His goal: to bring human factors practice and knowledge into the diving community to improve safety, performance, and enjoyment.