Johann Lohs: The Channel Hunter

Johann Lohs: The Channel Hunter

Johann Lohs: The Channel Hunter

BY JOHN GROGAN

|

|

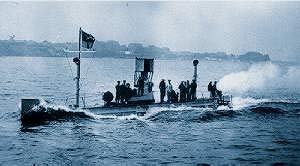

UB-57

|

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German navy

quickly realised the value of a large U-boat fleet and used its

boats to attack shipping all around the UK. Their aim was to deny

Britain both food and munitions as well as fresh troops in the

later years of the war. Initially, their focus was military and

merchant navy, but as the war progressed, all ships became

targetsÑthe most notable example being the RMS Lusitania sunk

in 1916. With submarine bases along the north German coast, the

Dutch coast and even inland in Belgium (using canals to get to the

North Sea), submarines quickly fanned out to form patrol zones in

the English Channel, the North Sea, around the Orkneys (near Scapa

Flow), the Irish Sea, the Atlantic and the northern approaches

around northern Ireland and western Scotland.

|

|

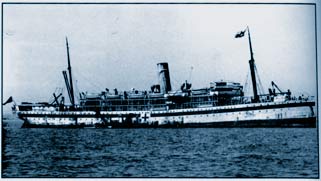

The RMS Kyarra

in an undated photo

|

At the time, submarine detection methods were at best primitive, relying on watchmen to spot submarines either on the surface or by the telltale wakes caused by their periscopes. In many cases, the first indication of a U-boat in the area was the wake caused by an incoming torpedo or by the explosion caused by impact.

The Imperial Navy largely employed three types of U-boat: the UB, UC and U classes. The UB class boat was a coastal submarine that carried ten torpedoes, accommodated thirty-four crewmembers and had a range of 8,500 kilometres; this limited its sorties to around the UK. The UC class was primarily a mine-laying boat. It carried seven torpedoes, eighteen mines, and accommodated a crew of twenty-six men; its range was 9,400 kilometres. The U class was an ocean-going U-boat with a range of 12,500 kilometres and was primarily designed to work further from home for longer periods. These boats operated in the Atlantic and some even made it as far as the east coast of the United States. This class of U-boat carried up to seventy-two mines and twelve torpedoes, as well as a larger deck gun, and was crewed by forty men.

|

|

Johann

Lohs

|

Although we know a great deal about the U-boat war, we know little about the men who fought it. Many have forgotten the numerous boats and captains who were engaged in this struggle. This essay will take a look at one such captain, Johann Lohs, a German U-boat captain who was responsible for many of this period's great wrecks, wrecks which today are to be found along the British south coast.

Lohs was born in June 1889 in Saxony and entered the Imperial Navy in 1909. In 1915, he was assigned to the U-75, where he served as a weapons officer, before finally receiving command of the UC-75 in 1917. After a successful stint, he was given command of the UB-57. The following is an account of some of his kills.

RMS Kyarra

The Kyarra was built in 1903 and for most of her life cruised in

Australian waters. However, with the outbreak of war, she was

requisitioned for use as a hospital ship and painted white with a

large red cross on her hull. Her top speed was 14 knots.

|

|

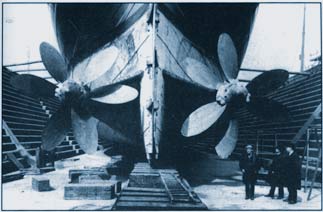

The RMS Kyarra

in drydock

|

On 26 May 1918, she was cruising past Anvil Point on the south coast on her way to Australia, when suddenly one of the lookouts shouted, "Torpedo approaching on the portside." With the alarm sounded, the ship started to turn hard to port, but it was too late; the torpedo struck mid-ships. The engine room quickly flooded and the ship started to settle in the water. Five people died in the explosion and an order to abandon ship was given. Twenty minutes after being struck, the ship slipped under the waves. After being satisfied with his kill, Johann Lohs slipped back into deeper water further out in the channel. Many passengers made it to the lifeboats and rowed to the nearby town of SwanageÑfrom which dive boats today operate to and from the Kyarra.

Today, the Kyarra is a very popular dive site with dive shuttles going back and forth to it all day in the summer. She lies fairly upright in about 30 meters (100 feet) of water. Each year, her holds give up more of the cargo that she once held, which has included many gold watches.

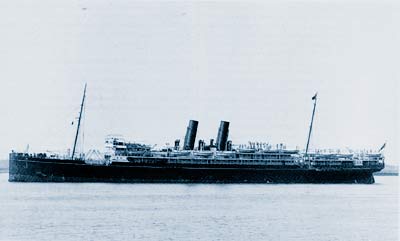

RMS Moldavia

The Moldavia was a 9,505-ton liner generally employed on the

London-Australia run before the war. In 1915, she was converted

into an armed merchant cruiser. In May 1918, while carrying troops

from Halifax, Nova Scotia to London, she was steaming down the east

of the channel near Brighton and Littlehampton, escorted by a

number of naval ships. On the early morning of May 23, Lohs heard

the faint sound of ships' engines and moved to investigate. In the

faint dawn glow, he spotted the convoy and moved closer, slipping

astern of the convoy, and remained on the surface until the last

possible minute. Finally, he dived and lined up the cross hairs of

his periscope before firing at the Moldavia.

|

|

The

RMSMoldavia

|

She was struck amidships, but the damage did not initially seem serious, so the Moldavia continued steaming on her course. The crew was mustered to battle stations and all ten guns were manned, but there was no one to shoot at. She steamed on for another fifteen minutes and then slowly started to settle in the water. The escort ships immediately responded to the attack by laying depth charges and, finally satisfied that the U-boat was put down, returned to help the survivors. There had been a large complement of soldiers in the compartment behind the torpedo impact, and fifty-six died immediately. It only took twenty minutes for the liner to sink beneath the waves.

Today, the Moldavia lies approximately in the middle of the channel in up to 50 meters (165 feet) of water. She lies on her port side with her highest point starting at 28 meters (92 feet). She is an amazing sight to behold with some of her guns pointing towards the surface. Due to her location and the strong tides that wash over her, visibility is often in excess of 20 meters (amazing by UK standards); sitting on the stern, a diver can see one-third of the entire wreck. There were in excess of 1,000 portholes on this ship and many are still firmly stuck in place.

The Moldavia is a sister ship of RMS Medina (Quest, Vol. 2, No 4).

Luxor

The Luxor was only a few weeks old when she met her fate on March

18, 1918. She left out of Cherbourg, France leading a small convoy

to Weymouth, her master frustrated at having to travel much slower

than the normal speed of 10 knots. At 2:10 am, the master saw the

wake of an incoming torpedo and ordered the helm hard to port, but

the ship could not respond in time. The torpedo struck her on her

starboard side and she went under in three minutes. The crew

immediately abandoned ship and were picked up by two escort

trawlers. To date, the Luxor has yet to be discovered.

Shirala

The Shirala was a 5,306-ton passenger and cargo ship built in 1901

for The British India Steam Navigation Company. She was used to

ferry passengers and cargo on scheduled routes to and from India.

On 29 June 1918, she started her final voyage bound for India fully

loaded with a very mixed cargo that included munitions, ivory,

wine, marmalade, lorry parts, spares for model T cars and sheets of

paper from the Bank of England to be printed as Rupees.

At 5: 12 pm, on 2 July 1918, the Shirala was four miles northeast of the Owers lightship vessel, when Lohs fired a torpedo, detonating amidships on the port side. Captain E. G. Murray Dickenson gave the order to abandon ship. All 200 passengers survived, but, sadly, eight out of the one hundred crewmen died when cold sea water came flooding into the stoke room, and caused a secondary explosion upon contact with the hot boilers.

The wreck today is well dived and a must for all divers. The Shirala is well broken up, and lies in approximately 22 meters (73 feet) of water. There are still brass detonating caps, marmalade jars and wine bottles scattered in the sand amongst aircraft bombs and lorry parts. Visibility is typically 4-9 meters.

The City of Brisbane

The City of Brisbane was heading for Buenos Aires when, on 13

August 1918, her lookouts spotted the telltale wake of an inbound

torpedo. It was too late to do anything, and within seconds she was

struck aft of hold number five. The side of the ship was completely

blown in and the engine room was completely open to the sea.

The ship immediately started to settle in the water, and within a few minutes the stern was on the seabed and the master ordered all hands to abandon ship. All managed to get clear, and within half an hour the bow slipped under the waves.

Today, she lies in 30 meters, 5-6 meters proud at the bows. This is the last recorded kill of the crew of the UB-57.

The Fates of UC-75 and UB-57

The UC-75Ñby now under the command of Oberleutant

SchmitzÑwas rammed on 31 May 1918 by HMS Fairy. Before

sinking, 13 crewmembers escaped and were captured. However, shortly

afterwards, HMS Fairy also sank as a result of damages sustained in

her collision with the much larger and newer U-boat. The UC-75 now

lies upright and intact in 42 meters. The deck gun, propeller and

torpedo tubes have been removed.

|

|

UB-57

|

After sinking the City of Brisbane, the UB-57 headed for home in Zeebrugge, Belgium. During the journey, having first checked that the horizon was clear, she started to surface to run on diesels and recharge her batteries. Upon surfacing, Lohs opened the hatch to find himself almost directly beneath a low-flying British airship. A crash dive was immediately ordered, but they had been spotted and the airship started dropping bombs. Fortunately, they evaded sinking and continued their journey home.

On 14 August 1918, Lohs radioed to base that he had sunk 15,000 tons of shipping and was returning to base. That night he started through the narrow and swept straits of Dover. Nothing more was ever heard from him but it is likely that he hit a mine near Zeebrugge. Lohs' body and those of some of his crew were washed up near the mouth of the river Scheldt about one week later. Lohs was one of the Imperial Navy's war heroes, having sunk an impressive seventy-six merchant ships and one warship, a total of 148,677 tons. During World War II, one of the U-boat flotillas operating from France was named in his honour.

UK Wreck Diving

Two world wars, as well as many centuries as an ocean-going nation,

have ensured a plentiful supply of wreck diving opportunities for

UK wreck divers. There are an estimated 500,000 wrecks around the

UK coast, some dating back almost 2,000 years. The First World War,

and the U-boat activity that played a role in it, has provided many

wrecks for divers. Some have become regular favourites of divers,

others have yet to be discovered. The English Channel offers a

large number of unknown and unexplored wrecks that keep UK divers

occupied throughout the summer months. Due to weather and

conditions, the typical diving season begins in April and ends in

October. Temperatures range from about 12¼ C in April to

17¼ C in September.

The more interesting and unexplored wrecks tend to be found in or close to the two shipping lanes in the middle of the channel. Here, depths range from about 40 meters (132 feet) in the east to in excess of 100 meters (330 feet) in the west. These tend to be challenging dives, not least of which is a result of trying to avoid the heavy traffic during decompression. However, the unknown wrecks that can be found compensate for the additional planning and logistics required.

Sources

Steve Shovlar. "Dorset Shipwrecks." Freestyle Publications Ltd,

1996.

Neil Maw. "World War One Channel Wrecks." Underwater World

Publications Ltd, 1999.

John Grogan works in Investment Banking. He has been diving for twelve years and is certified in Trimix, Rebreathers and Cave DivingÑmainly through GUE. He is one of the founding members of the UK DIR team, which came together at the end of 1997, and is actively involved both in organizing cave diving expeditions to France and elsewhere, and in setting up mid-channel exploration dives for the team. He is also one of the Decoplanner guinea pigs.